Volume XII, Issue XV

Phantasies

By George MacDonald, Chapter 9

O lady! we receive but what we give,

And in our life alone does nature live:

Ours is her wedding garments ours her shroud!

Ah! from the soul itself must issue forth,

A light, a glory, a fair luminous cloud,

Enveloping the Earth--

And from the soul itself must there be sent

A sweet and potent voice of its own birth,

Of all sweet sounds the life and element!"

~ from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Dejection: An Ode".

From this time, until I arrived at the palace of Fairy Land, I can attempt no consecutive account of my wanderings and adventures. Everything, henceforward, existed for me in its relation to my attendant. What influence he exercised upon everything into contact with which I was brought, may be understood from a few detached instances. To begin with this very day on which he first joined me: after I had walked heartlessly along for two or three hours, I was very weary, and lay down to rest in a most delightful part of the forest, carpeted with wild flowers. I lay for half an hour in a dull repose, and then got up to pursue my way. The flowers on the spot where I had lain were crushed to the earth: but I saw that they would soon lift their heads and rejoice again in the sun and air. Not so those on which my shadow had lain. The very outline of it could be traced in the withered lifeless grass, and the scorched and shrivelled flowers which stood there, dead, and hopeless of any resurrection. I shuddered, and hastened away with sad forebodings.

In a few days, I had reason to dread an extension of its baleful influences from the fact, that it was no longer confined to one position in regard to myself. Hitherto, when seized with an irresistible desire to look on my evil demon (which longing would unaccountably seize me at any moment, returning at longer or shorter intervals, sometimes every minute), I had to turn my head backwards, and look over my shoulder; in which position, as long as I could retain it, I was fascinated. But one day, having come out on a clear grassy hill, which commanded a glorious prospect, though of what I cannot now tell, my shadow moved round, and came in front of me. And, presently, a new manifestation increased my distress. For it began to coruscate, and shoot out on all sides a radiation of dim shadow. These rays of gloom issued from the central shadow as from a black sun, lengthening and shortening with continual change. But wherever a ray struck, that part of earth, or sea, or sky, became void, and desert, and sad to my heart. On this, the first development of its new power, one ray shot out beyond the rest, seeming to lengthen infinitely, until it smote the great sun on the face, which withered and darkened beneath the blow. I turned away and went on. The shadow retreated to its former position; and when I looked again, it had drawn in all its spears of darkness, and followed like a dog at my heels.

Once, as I passed by a cottage, there came out a lovely fairy child, with two wondrous toys, one in each hand. The one was the tube through which the fairy-gifted poet looks when he beholds the same thing everywhere; the other that through which he looks when he combines into new forms of loveliness those images of beauty which his own choice has gathered from all regions wherein he has travelled. Round the child's head was an aureole of emanating rays. As I looked at him in wonder and delight, round crept from behind me the something dark, and the child stood in my shadow. Straightway he was a commonplace boy, with a rough broad-brimmed straw hat, through which brim the sun shone from behind. The toys he carried were a multiplying-glass and a kaleidoscope. I sighed and departed.

One evening, as a great silent flood of western gold flowed through an avenue in the woods, down the stream, just as when I saw him first, came the sad knight, riding on his chestnut steed.

But his armour did not shine half so red as when I saw him first.

Many a blow of mighty sword and axe, turned aside by the strength of his mail, and glancing adown the surface, had swept from its path the fretted rust, and the glorious steel had answered the kindly blow with the thanks of returning light. These streaks and spots made his armour look like the floor of a forest in the sunlight. His forehead was higher than before, for the contracting wrinkles were nearly gone; and the sadness that remained on his face was the sadness of a dewy summer twilight, not that of a frosty autumn morn. He, too, had met the Alder-maiden as I, but he had plunged into the torrent of mighty deeds, and the stain was nearly washed away. No shadow followed him. He had not entered the dark house; he had not had time to open the closet door. "Will he ever look in?" I said to myself. "Must his shadow find him some day?" But I could not answer my own questions.

We travelled together for two days, and I began to love him. It was plain that he suspected my story in some degree; and I saw him once or twice looking curiously and anxiously at my attendant gloom, which all this time had remained very obsequiously behind me; but I offered no explanation, and he asked none. Shame at my neglect of his warning, and a horror which shrunk from even alluding to its cause, kept me silent; till, on the evening of the second day, some noble words from my companion roused all my heart; and I was at the point of falling on his neck, and telling him the whole story; seeking, if not for helpful advice, for of that I was hopeless, yet for the comfort of sympathy--when round slid the shadow and inwrapt my friend; and I could not trust him.

The glory of his brow vanished; the light of his eye grew cold; and I held my peace. The next morning we parted.

But the most dreadful thing of all was, that I now began to feel something like satisfaction in the presence of the shadow. I began to be rather vain of my attendant, saying to myself, "In a land like this, with so many illusions everywhere, I need his aid to disenchant the things around me. He does away with all appearances, and shows me things in their true colour and form. And I am not one to be fooled with the vanities of the common crowd. I will not see beauty where there is none. I will dare to behold things as they are. And if I live in a waste instead of a paradise, I will live knowing where I live." But of this a certain exercise of his power which soon followed quite cured me, turning my feelings towards him once more into loathing and distrust. It was thus:

One bright noon, a little maiden joined me, coming through the wood in a direction at right angles to my path. She came along singing and dancing, happy as a child, though she seemed almost a woman. In her hands--now in one, now in another--she carried a small globe, bright and clear as the purest crystal. This seemed at once her plaything and her greatest treasure. At one moment, you would have thought her utterly careless of it, and at another, overwhelmed with anxiety for its safety. But I believe she was taking care of it all the time, perhaps not least when least occupied about it. She stopped by me with a smile, and bade me good day with the sweetest voice. I felt a wonderful liking to the child--for she produced on me more the impression of a child, though my understanding told me differently. We talked a little, and then walked on together in the direction I had been pursuing. I asked her about the globe she carried, but getting no definite answer, I held out my hand to take it. She drew back, and said, but smiling almost invitingly the while, "You must not touch it;"--then, after a moment's pause--"Or if you do, it must be very gently." I touched it with a finger. A slight vibratory motion arose in it, accompanied, or perhaps manifested, by a faint sweet sound. I touched it again, and the sound increased. I touched it the third time: a tiny torrent of harmony rolled out of the little globe. She would not let me touch it any more.

We travelled on together all that day. She left me when twilight came on; but next day, at noon, she met me as before, and again we travelled till evening. The third day she came once more at noon, and we walked on together. Now, though we had talked about a great many things connected with Fairy Land, and the life she had led hitherto, I had never been able to learn anything about the globe. This day, however, as we went on, the shadow glided round and inwrapt the maiden. It could not change her. But my desire to know about the globe, which in his gloom began to waver as with an inward light, and to shoot out flashes of many-coloured flame, grew irresistible. I put out both my hands and laid hold of it. It began to sound as before. The sound rapidly increased, till it grew a low tempest of harmony, and the globe trembled, and quivered, and throbbed between my hands. I had not the heart to pull it away from the maiden, though I held it in spite of her attempts to take it from me; yes, I shame to say, in spite of her prayers, and, at last, her tears. The music went on growing in, intensity and complication of tones, and the globe vibrated and heaved; till at last it burst in our hands, and a black vapour broke upwards from out of it; then turned, as if blown sideways, and enveloped the maiden, hiding even the shadow in its blackness. She held fast the fragments, which I abandoned, and fled from me into the forest in the direction whence she had come, wailing like a child, and crying, "You have broken my globe; my globe is broken--my globe is broken!" I followed her, in the hope of comforting her; but had not pursued her far, before a sudden cold gust of wind bowed the tree-tops above us, and swept through their stems around us; a great cloud overspread the day, and a fierce tempest came on, in which I lost sight of her. It lies heavy on my heart to this hour. At night, ere I fall asleep, often, whatever I may be thinking about, I suddenly hear her voice, crying out, "You have broken my globe; my globe is broken; ah, my globe!"

Here I will mention one more strange thing; but whether this peculiarity was owing to my shadow at all, I am not able to assure myself. I came to a village, the inhabitants of which could not at first sight be distinguished from the dwellers in our land. They rather avoided than sought my company, though they were very pleasant when I addressed them. But at last I observed, that whenever I came within a certain distance of any one of them, which distance, however, varied with different individuals, the whole appearance of the person began to change; and this change increased in degree as I approached. When I receded to the former distance, the former appearance was restored. The nature of the change was grotesque, following no fixed rule. The nearest resemblance to it that I know, is the distortion produced in your countenance when you look at it as reflected in a concave or convex surface--say, either side of a bright spoon. Of this phenomenon I first became aware in rather a ludicrous way. My host's daughter was a very pleasant pretty girl, who made herself more agreeable to me than most of those about me. For some days my companion-shadow had been less obtrusive than usual; and such was the reaction of spirits occasioned by the simple mitigation of torment, that, although I had cause enough besides to be gloomy, I felt light and comparatively happy. My impression is, that she was quite aware of the law of appearances that existed between the people of the place and myself, and had resolved to amuse herself at my expense; for one evening, after some jesting and raillery, she, somehow or other, provoked me to attempt to kiss her. But she was well defended from any assault of the kind. Her countenance became, of a sudden, absurdly hideous; the pretty mouth was elongated and otherwise amplified sufficiently to have allowed of six simultaneous kisses. I started back in bewildered dismay; she burst into the merriest fit of laughter, and ran from the room. I soon found that the same undefinable law of change operated between me and all the other villagers; and that, to feel I was in pleasant company, it was absolutely necessary for me to discover and observe the right focal distance between myself and each one with whom I had to do. This done, all went pleasantly enough. Whether, when I happened to neglect this precaution, I presented to them an equally ridiculous appearance, I did not ascertain; but I presume that the alteration was common to the approximating parties. I was likewise unable to determine whether I was a necessary party to the production of this strange transformation, or whether it took place as well, under the given circumstances, between the inhabitants themselves.

(to be continued)

Staunton's Romanesque-Revival Marquis Building, constructed in 1895, originally housed the offices of architect T. J. Collins. Collins is responsible for the design of over 200 buildings in the historic city. A men's clothing shop once occupied the street level and the large umbrella was installed on the facade as a trade sign. Today the building is often referred to as 'The Umbrella Building.' -- Photos by Bob Kirchman

'The Light Within'

Painting by Savhanna Herndon

'The Light Within,' Acrylic on Canvas, 20" x 24" by Savhanna Herndon. This is a painting exploring the concept of IMAGO DEI and the Spirit of God within us (Romans 8:9).

And I heard a great voice out of heaven saying, Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be with them, and be their God." -- Revelation 21:3

Tabernacle Presbyterian Church in Waynesboro, Virginia was host to a wonderful celebration of art centered around the theme of God tabernacling among His People. It was part of the church's celebration of its 25th anniversary. There was an art exhibition with music and refreshments. When the theme was announced it was obvious what pieces we should offer to the show.

'Journey to Jesus'

Mural by Kristina Elaine Greer and Bob Kirchman

Journey to Jesus, a mural depicting the nations coming to Jesus in the New Heaven and New Earth described in Revelation 21. Mural by Kristina Elaine Greer and Bob Kirchman.

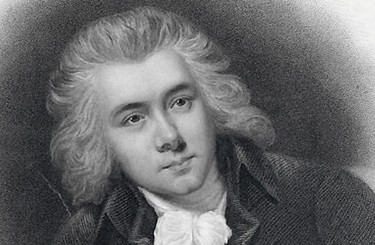

Public Service as a Holy Calling

The Life of William Wilberforce

When we really understand how short and uncertain our life is here, then we see things in their true proportions; we are prompted to act out of the conviction that “the night cometh when no man can work.” This thought produces a firm texture to our lives; it hardens us against the wind of fortune, and keeps us from being deeply penetrated by the cares and interests, the good or evil of this transitory state. When we have a realistic impression of the relative value of temporal and eternal things, this helps our souls maintain a dignified composure through all the vicissitudes of life. It brings our diligence to life, while it moderates our impulsive passions; it urges us to pursue justice, yet it checks any undue worry about the success of our endeavors.” – William Wilberforce

Get used to paying close attention to all those who live in a careless and inconsiderate world, who are in such imminent danger and are so ignorant of their peril. Think about these people, until you feel pity for them. This sympathy will melt your heart. Once there is room in your heart for Christ’s love, this will produce – almost without your noticing – a habitual feeling of gentle sympathy.” – William Wilberforce

Philosophy is designed only for those who are educated. It tends to divide society even more, breaking it into two parts: those who have money and leisure for learning, and those who don’t. But – blessed be God – the faith that I am recommending was designed not for the rich but the poor. It removes the distinction of class and wealth, and changes the entire social fabric. This faith makes all people useful members of civil society.” – William Wilberforce

Although Wilberforce is most known today for his work as an abolitionist, it is well to remember that for him the ‘Reformation of Manners’ had far more to do with the moral fiber of the nation as a whole. Does Wilberforce have a message for modern society? If you consider that the culture he lived in was a mess and needed badly the reform that subsequently guided it, the answer is a resounding “Yes!” Those who desire a compassionate society would do well to heed him. Those who seek a ‘compassionate’ society apart from Divine oversight would do well to remember that “if God does not exist, is murder permissible?” is one question that will quickly arise. Indeed one should ask if a neutral pluralism is to be pursued to the exclusion of virtues found in Holy Writ. Today Wilberforce’s Britain wrestles with this. She has widely embraced secularism, but has elected Prime Minister Theresa May, a devout Christian, who says unequivocally that Britain is a “Christian Nation.” Prime Minister May, like Wilberforce, is guided in her public service by her personal faith. These are difficult days for England, but the foundations built by Wilberforce will serve her well in the days ahead.

(to be continued)

Building the 'Chunnel'

Connecting England to Mainland Europe

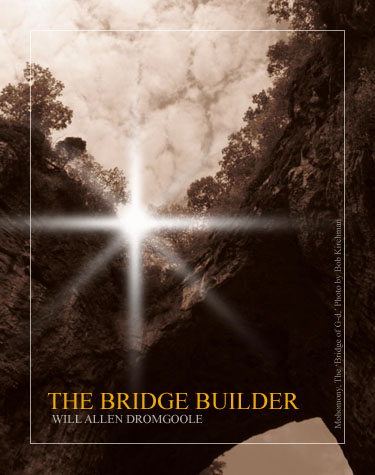

Mohomony, the 'Bridge of G-d,' as the Monocans called it is the namesake of Rockbridge County in Virginia.

The Bridge Builder

By Will Allen Dromgoole

An old man going a lone highway,

Came, at the evening cold and gray,

To a chasm vast and deep and wide.

Through which was flowing a sullen tide

The old man crossed in the twilight dim,

The sullen stream had no fear for him;

But he turned when safe on the other side

And built a bridge to span the tide.

Old man,” said a fellow pilgrim near,

“You are wasting your strength with building here;

Your journey will end with the ending day,

You never again will pass this way;

You’ve crossed the chasm, deep and wide,

Why build this bridge at evening tide?”

The builder lifted his old gray head;

“Good friend, in the path I have come,” he said,

“There followed after me to-day

A youth whose feet must pass this way.

This chasm that has been as naught to me

To that fair-haired youth may a pitfall be;

He, too, must cross in the twilight dim;

Good friend, I am building this bridge for him!”

Source: Father: An Anthology of Verse (EP Dutton and Company, 1931)

Cherry Blossoms

Cherry Blossoms at the Jefferson memorial. Photos by Bob Kirchman