Volume XII, Issue XXVIII

Phantasies

By George Macdonald, Chapter 22

No one has my form but the I."

~ Schoppe, in Jean Pau's "Titan".

Joy's a subtil elf.

I think man's happiest when he forgets himself."

~ Cyril Tourneur, "The Revenger's Tragedy".

On the third day of my journey, I was riding gently along a road, apparently little frequented, to judge from the grass that grew upon it. I was approaching a forest. Everywhere in Fairy Land forests are the places where one may most certainly expect adventures. As I drew near, a youth, unarmed, gentle, and beautiful, who had just cut a branch from a yew growing on the skirts of the wood, evidently to make himself a bow, met me, and thus accosted me:

Sir knight, be careful as thou ridest through this forest; for it is said to be strangely enchanted, in a sort which even those who have been witnesses of its enchantment can hardly describe."

I thanked him for his advice, which I promised to follow, and rode on. But the moment I entered the wood, it seemed to me that, if enchantment there was, it must be of a good kind; for the Shadow, which had been more than usually dark and distressing, since I had set out on this journey, suddenly disappeared. I felt a wonderful elevation of spirits, and began to reflect on my past life, and especially on my combat with the giants, with such satisfaction, that I had actually to remind myself, that I had only killed one of them; and that, but for the brothers, I should never have had the idea of attacking them, not to mention the smallest power of standing to it. Still I rejoiced, and counted myself amongst the glorious knights of old; having even the unspeakable presumption--my shame and self- condemnation at the memory of it are such, that I write it as the only and sorest penance I can perform--to think of myself (will the world believe it?) as side by side with Sir Galahad! Scarcely had the thought been born in my mind, when, approaching me from the left, through the trees, I espied a resplendent knight, of mighty size, whose armour seemed to shine of itself, without the sun. When he drew near, I was astonished to see that this armour was like my own; nay, I could trace, line for line, the correspondence of the inlaid silver to the device on my own. His horse, too, was like mine in colour, form, and motion; save that, like his rider, he was greater and fiercer than his counterpart. The knight rode with beaver up. As he halted right opposite to me in the narrow path, barring my way, I saw the reflection of my countenance in the centre plate of shining steel on his breastplate. Above it rose the same face--his face--only, as I have said, larger and fiercer. I was bewildered. I could not help feeling some admiration of him, but it was mingled with a dim conviction that he was evil, and that I ought to fight with him.

Let me pass," I said.

When I will," he replied.

Something within me said: "Spear in rest, and ride at him! else thou art for ever a slave."

I tried, but my arm trembled so much, that I could not couch my lance. To tell the truth, I, who had overcome the giant, shook like a coward before this knight. He gave a scornful laugh, that echoed through the wood, turned his horse, and said, without looking round, "Follow me."

I obeyed, abashed and stupefied. How long he led, and how long I followed, I cannot tell. "I never knew misery before," I said to myself. "Would that I had at least struck him, and had had my death-blow in return! Why, then, do I not call to him to wheel and defend himself? Alas! I know not why, but I cannot. One look from him would cow me like a beaten hound." I followed, and was silent.

At length we came to a dreary square tower, in the middle of a dense forest. It looked as if scarce a tree had been cut down to make room for it. Across the very door, diagonally, grew the stem of a tree, so large that there was just room to squeeze past it in order to enter. One miserable square hole in the roof was the only visible suggestion of a window. Turret or battlement, or projecting masonry of any kind, it had none. Clear and smooth and massy, it rose from its base, and ended with a line straight and unbroken. The roof, carried to a centre from each of the four walls, rose slightly to the point where the rafters met. Round the base lay several little heaps of either bits of broken branches, withered and peeled, or half-whitened bones; I could not distinguish which. As I approached, the ground sounded hollow beneath my horse's hoofs. The knight took a great key from his pocket, and reaching past the stem of the tree, with some difficulty opened the door. "Dismount," he commanded. I obeyed. He turned my horse's head away from the tower, gave him a terrible blow with the flat side of his sword, and sent him madly tearing through the forest.

Now," said he, "enter, and take your companion with you."

I looked round: knight and horse had vanished, and behind me lay the horrible shadow. I entered, for I could not help myself; and the shadow followed me. I had a terrible conviction that the knight and he were one. The door closed behind me.

Now I was indeed in pitiful plight. There was literally nothing in the tower but my shadow and me. The walls rose right up to the roof; in which, as I had seen from without, there was one little square opening. This I now knew to be the only window the tower possessed. I sat down on the floor, in listless wretchedness. I think I must have fallen asleep, and have slept for hours; for I suddenly became aware of existence, in observing that the moon was shining through the hole in the roof. As she rose higher and higher, her light crept down the wall over me, till at last it shone right upon my head. Instantaneously the walls of the tower seemed to vanish away like a mist. I sat beneath a beech, on the edge of a forest, and the open country lay, in the moonlight, for miles and miles around me, spotted with glimmering houses and spires and towers. I thought with myself, "Oh, joy! it was only a dream; the horrible narrow waste is gone, and I wake beneath a beech-tree, perhaps one that loves me, and I can go where I will." I rose, as I thought, and walked about, and did what I would, but ever kept near the tree; for always, and, of course, since my meeting with the woman of the beech-tree far more than ever, I loved that tree. So the night wore on. I waited for the sun to rise, before I could venture to renew my journey. But as soon as the first faint light of the dawn appeared, instead of shining upon me from the eye of the morning, it stole like a fainting ghost through the little square hole above my head; and the walls came out as the light grew, and the glorious night was swallowed up of the hateful day. The long dreary day passed. My shadow lay black on the floor. I felt no hunger, no need of food. The night came. The moon shone. I watched her light slowly descending the wall, as I might have watched, adown the sky, the long, swift approach of a helping angel. Her rays touched me, and I was free. Thus night after night passed away. I should have died but for this. Every night the conviction returned, that I was free. Every morning I sat wretchedly disconsolate. At length, when the course of the moon no longer permitted her beams to touch me, the night was dreary as the day.

When I slept, I was somewhat consoled by my dreams; but all the time I dreamed, I knew that I was only dreaming. But one night, at length, the moon, a mere shred of pallor, scattered a few thin ghostly rays upon me; and I think I fell asleep and dreamed. I sat in an autumn night before the vintage, on a hill overlooking my own castle. My heart sprang with joy. Oh, to be a child again, innocent, fearless, without shame or desire! I walked down to the castle. All were in consternation at my absence. My sisters were weeping for my loss. They sprang up and clung to me, with incoherent cries, as I entered. My old friends came flocking round me. A gray light shone on the roof of the hall. It was the light of the dawn shining through the square window of my tower. More earnestly than ever, I longed for freedom after this dream; more drearily than ever, crept on the next wretched day. I measured by the sunbeams, caught through the little window in the trap of my tower, how it went by, waiting only for the dreams of the night.

About noon, I started as if something foreign to all my senses and all my experience, had suddenly invaded me; yet it was only the voice of a woman singing. My whole frame quivered with joy, surprise, and the sensation of the unforeseen. Like a living soul, like an incarnation of Nature, the song entered my prison-house. Each tone folded its wings, and laid itself, like a caressing bird, upon my heart. It bathed me like a sea; inwrapt me like an odorous vapour; entered my soul like a long draught of clear spring-water; shone upon me like essential sunlight; soothed me like a mother's voice and hand. Yet, as the clearest forest-well tastes sometimes of the bitterness of decayed leaves, so to my weary, prisoned heart, its cheerfulness had a sting of cold, and its tenderness unmanned me with the faintness of long-departed joys. I wept half-bitterly, half-luxuriously; but not long. I dashed away the tears, ashamed of a weakness which I thought I had abandoned. Ere I knew, I had walked to the door, and seated myself with my ears against it, in order to catch every syllable of the revelation from the unseen outer world. And now I heard each word distinctly. The singer seemed to be standing or sitting near the tower, for the sounds indicated no change of place. The song was something like this:

The sun, like a golden knot on high,

Gathers the glories of the sky,

And binds them into a shining tent,

Roofing the world with the firmament.

And through the pavilion the rich winds blow,

And through the pavilion the waters go.

And the birds for joy, and the trees for prayer,

Bowing their heads in the sunny air,

And for thoughts, the gently talking springs,

That come from the centre with secret things--

All make a music, gentle and strong,

Bound by the heart into one sweet song.

And amidst them all, the mother Earth

Sits with the children of her birth;

She tendeth them all, as a mother hen

Her little ones round her, twelve or ten:

Oft she sitteth, with hands on knee,

Idle with love for her family.

Go forth to her from the dark and the dust,

And weep beside her, if weep thou must;

If she may not hold thee to her breast,

Like a weary infant, that cries for rest

At least she will press thee to her knee,

And tell a low, sweet tale to thee,

Till the hue to thy cheeky and the light to thine eye,

Strength to thy limbs, and courage high

To thy fainting heart, return amain,

And away to work thou goest again.

From the narrow desert, O man of pride,

Come into the house, so high and wide.

Hardly knowing what I did, I opened the door. Why had I not done so before? I do not know.

At first I could see no one; but when I had forced myself past the tree which grew across the entrance, I saw, seated on the ground, and leaning against the tree, with her back to my prison, a beautiful woman. Her countenance seemed known to me, and yet unknown. She looked at me and smiled, when I made my appearance.

Ah! were you the prisoner there? I am very glad I have wiled you out."

Do you know me then?"

Do you not know me? But you hurt me, and that, I suppose, makes it easy for a man to forget. You broke my globe. Yet I thank you. Perhaps I owe you many thanks for breaking it. I took the pieces, all black, and wet with crying over them, to the Fairy Queen. There was no music and no light in them now. But she took them from me, and laid them aside; and made me go to sleep in a great hall of white, with black pillars, and many red curtains. When I woke in the morning, I went to her, hoping to have my globe again, whole and sound; but she sent me away without it, and I have not seen it since. Nor do I care for it now. I have something so much better. I do not need the globe to play to me; for I can sing. I could not sing at all before. Now I go about everywhere through Fairy Land, singing till my heart is like to break, just like my globe, for very joy at my own songs. And wherever I go, my songs do good, and deliver people. And now I have delivered you, and I am so happy."

She ceased, and the tears came into her eyes.

All this time, I had been gazing at her; and now fully recognised the face of the child, glorified in the countenance of the woman.

I was ashamed and humbled before her; but a great weight was lifted from my thoughts. I knelt before her, and thanked her, and begged her to forgive me.

Rise, rise," she said; "I have nothing to forgive; I thank you. But now I must be gone, for I do not know how many may be waiting for me, here and there, through the dark forests; and they cannot come out till I come."

She rose, and with a smile and a farewell, turned and left me. I dared not ask her to stay; in fact, I could hardly speak to her. Between her and me, there was a great gulf. She was uplifted, by sorrow and well-doing, into a region I could hardly hope ever to enter. I watched her departure, as one watches a sunset. She went like a radiance through the dark wood, which was henceforth bright to me, from simply knowing that such a creature was in it.

She was bearing the sun to the unsunned spots. The light and the music of her broken globe were now in her heart and her brain. As she went, she sang; and I caught these few words of her song; and the tones seemed to linger and wind about the trees after she had disappeared:

Thou goest thine, and I go mine--

Many ways we wend;

Many days, and many ways,

Ending in one end.

Many a wrong, and its curing song;

Many a road, and many an inn;

Room to roam, but only one home

For all the world to win.

And so she vanished. With a sad heart, soothed by humility, and the knowledge of her peace and gladness, I bethought me what now I should do. First, I must leave the tower far behind me, lest, in some evil moment, I might be once more caged within its horrible walls. But it was ill walking in my heavy armour; and besides I had now no right to the golden spurs and the resplendent mail, fitly dulled with long neglect. I might do for a squire; but I honoured knighthood too highly, to call myself any longer one of the noble brotherhood. I stripped off all my armour, piled it under the tree, just where the lady had been seated, and took my unknown way, eastward through the woods. Of all my weapons, I carried only a short axe in my hand.

Then first I knew the delight of being lowly; of saying to myself, "I am what I am, nothing more." "I have failed," I said, "I have lost myself--would it had been my shadow." I looked round: the shadow was nowhere to be seen. Ere long, I learned that it was not myself, but only my shadow, that I had lost. I learned that it is better, a thousand-fold, for a proud man to fall and be humbled, than to hold up his head in his pride and fancied innocence. I learned that he that will be a hero, will barely be a man; that he that will be nothing but a doer of his work, is sure of his manhood. In nothing was my ideal lowered, or dimmed, or grown less precious; I only saw it too plainly, to set myself for a moment beside it. Indeed, my ideal soon became my life; whereas, formerly, my life had consisted in a vain attempt to behold, if not my ideal in myself, at least myself in my ideal. Now, however, I took, at first, what perhaps was a mistaken pleasure, in despising and degrading myself. Another self seemed to arise, like a white spirit from a dead man, from the dumb and trampled self of the past. Doubtless, this self must again die and be buried, and again, from its tomb, spring a winged child; but of this my history as yet bears not the record.

Self will come to life even in the slaying of self; but there is ever something deeper and stronger than it, which will emerge at last from the unknown abysses of the soul: will it be as a solemn gloom, burning with eyes? or a clear morning after the rain? or a smiling child, that finds itself nowhere, and everywhere?

(to be continued)

Stones of Remembrance

Short Story by Bob Kirchman

Did I ever tell you the story about my Great Grandfather?” Rupert Zimmerman said casually to Pastor Jon Greene as they sat in Green’s office in the little chapel on Big Diomede.

The two often talked regularly now after the events on the great Bering Strait Bridge that had taken a driver’s life and had cemented Zimmerman’s decision to put his faith in one far greater than himself. The way the story was often retold by Zimmerman’s descendants, the transformation had been a complete and sudden one. Again, the real story moves a lot slower. Zimmerman himself had moved on from frequent dinner guest to disciple. In Jon Greene’s wildest dreams he never thought that the business of multiplying faithful followers of Jesus Christ would include the ruthless builder of bridges, but that it did. Healing Zimmerman’s war wounds took a long time. The battle of Anchorage and a kidnapping on the Taiga had left raw open wounds in the man that Zimmerman himself thought impossible to heal.

But at Greene’s insistence, Rupert opened doors he feared to open. It was there that he met his own Great Grandfather who would become a part of his own journey.

My Great Grandfather Tolbert Saunders Dalton was born in Robertson County, Tennessee, close to Nashville. He was seventeen When the War between the States started. He joined the 49th Regiment of Tennessee Volunteers and had a long and distinguished career as a soldier. He saw many battles, some of them quite fierce, and the sight and sound of men dying around him led him to preach the Gospel. By the light of many a campfire, my Great Grandfather shared the simple message of redemption in Christ.

He served under General Nathan B. Forrest and saw action in some of the battles for control of the Mississippi. When Union troops advanced on Memphis, preparing to attack at dawn the next day, General Forrest was outnumbered ten to one. He did not have the artillery to protect the city, but he did have at his disposal a fair number of farm wagons and many willing workers like young Dalton, who had lied about his age to join the army. All night long, the boys hollowed out the ends of tree trunks and blacked them to look like cannon. Then each ‘cannon’ was positioned on a set of wagon wheels. The faux cannon were positioned for maximum effect along the banks of the river and then General Forrest demanded surrender! In a dangerous bluff Forrest’s 300 men captured 3,000 would-be attackers.

Tolbert Dalton was later assigned to spy duty. He once carried a message to General Forrest through enemy lines by pretending to be a deaf and dumb farm boy. Seeing an unexpected checkpoint, he quickly stuffed the message in his mouth and made signs to the soldiers. He was quick-minded enough to sign for clarification when one of the soldiers said “go ahead.”

Wounded in action, Dalton spent several months out of action and then joined the Seventh Kentucky Volunteers. In one battle the flag was shot down and young Tolbert rose to replant it in the breastworks. When it was shot down again, Dalton rallied the troops by standing to hold the flag in place. Enemy fire ripped his shirt but miraculously he was unscathed. His courage under fire earned him the rank of Major. The experience affirmed G-d’s calling in the young soldier’s heart. When the war was over, Dalton went to Medical School and became a doctor but the needs of men’s souls called him to the work that had begun around the campfires of his regiment. Preaching became Dalton’s sole vocation and he eventually settled in the town of Stanley in Page County, Virginia. One of my most treasured possessions is a copy of Wilmore’s New Analytical Reference Bible that my Grandfather once used.

I kept it solely as a connection point to my past, but after my discipleship began, it became so much more. After the war, Dalton sought to bind the nation’s wounds, but his journey took him beyond physical healing to the spiritual. Reading his war experiences and his subsequent “Life and Labors of a Poor Sinner,” I saw how his Citizenship had been transferred again. He was now not longer a Tennessean or a Virginian, or a Confederate, but a man of the Kingdom of Heaven. That is what propelled the best season of the man’s life.

But there was more to Dalton’s life than one might imagine. He became a minister of G-d and raised eight children! Probably the most interesting of these was his son, Tolbert Percy Dalton, known as ‘Jack’ who played professional baseball in Detroit from 1910 to 1916. He mysteriously vanished on July 4, 1948, from Catonsville, Maryland, while walking to a church service. Speculation abounded as to what happened to him. We all suspected that he had gone to Alaska to seek his fortune or something like that. “G-d has no Grandchildren,” and I suspect it was too much to follow in the old man’s footsteps. Years later we learned that he had died of a heart attack in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania two years after he disappeared.” Rupert went on to examine how a life that G-d used was not always something that read as a beautiful novel. Life did not always make sense… but the comfort was always that there was more to life… always, than what you could see.

It was growing late. The work of two great bridge builders pressed upon them. The man who brought together continents embraced the man who brought together men and the Kingdom. The conversation would be continued.

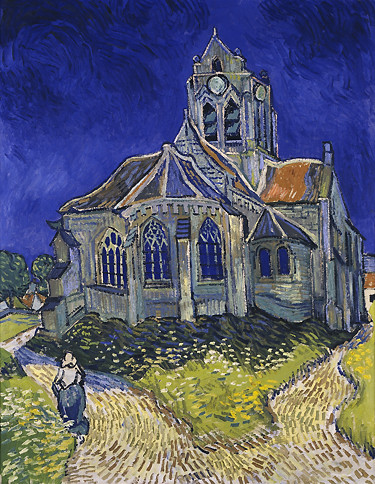

Transformation

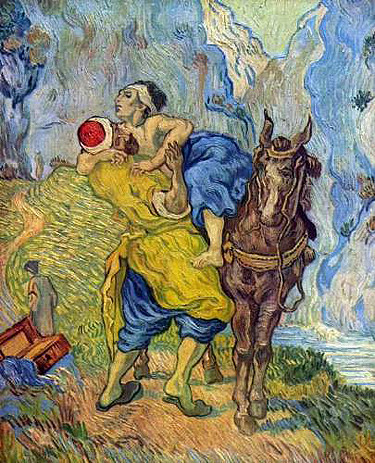

A powerful scene alludes to an even more powerful reality.

The Doctor: Between you and me, in a hundred words, where do you think Van Gogh rates in the history of art?

Curator: Well... um... big question, but, to me Van Gogh is the finest painter of them all. Certainly the most popular, great painter of all time. The most beloved, his command of colour most magnificent. He transformed the pain of his tormented life into ecstatic beauty. Pain is easy to portray, but to use your passion and pain to portray the ecstasy and joy and magnificence of our world, no one had ever done it before. Perhaps no one ever will again. To my mind, that strange, wild man who roamed the fields of Provence was not only the world's greatest artist, but also one of the greatest men who ever lived.

*****

And I heard a great voice out of heaven saying, Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be with them, and be their God.

And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.

And he that sat upon the throne said, Behold, I make all things new. And he said unto me, Write: for these words are true and faithful.”

-- Revelation 21:3-5

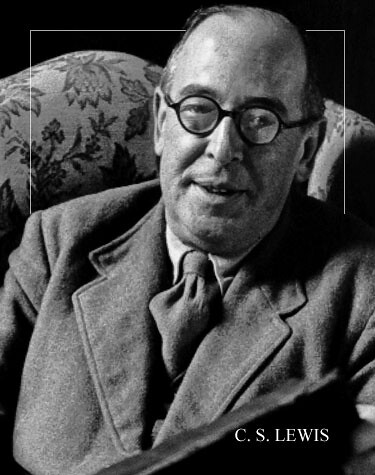

Worldview is everything. In Christ we have the one who actually transforms the pain and torment of this life into something beautiful. Here is a great truth that is beyond our understanding, yet the Divine Himself is the Master who completes the tapestries of our lives… inverting them to reveal His beautiful hand. This is a beautiful story, but may I suggest that it is beautiful because we yearn for what the Doctor and Amy were able to show Vincent and it is beautiful because Christ promises to show us the same. From C. S. Lewis and George MacDonald we learn that great story conveys great truth. Lewis shows us that those longings in us that this world cannot fulfill point to the fact that we were created for a better world.

History is not quite kind to Van Gogh, in fact the brief version often leaves you the memory of his madness. Yet here are some thoughts from the man himself. I think he is worthy of some study:

I feel that there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people.”

If you hear a voice within you say 'you cannot paint,' then by all means paint, and that voice will be silenced.”

Love many things, for therein lies the true strength, and whosoever loves much performs much, and can accomplish much, and what is done in love is done well.”

I wanted to know more, and in researching this I discovered William Havlicek, Ph. D , who wrote “Van Gogh’s Untold Journey” (Creative Storytellers). I knew that Van Gogh had some Faith because I had used a quote of his about church steeples a while ago. What I didn’t realize was the depth of his Faith.

Havlicek points out that the current drive by the academy toward secularization makes Van Gogh’s Faith practically unknown. Yet the man himself sought to serve God with his art: “…to try to understand the real significance of what the great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces, that leads to God. One man wrote or told it in a book, another in a picture.”

And about his relationship with prostitute, Sien Hoornik, consider the man’s own writing: “I met a pregnant woman, deserted by the man whose child she carried. A pregnant woman who had to walk the streets in winter, had to earn her bread, you understand how, I took this woman for a model and have worked with her all winter. I could not pay her the full wages of a model, but that did not prevent my paying her rent, and, thank God, so far I have been able to protect her and her child from hunger and cold by sharing my own bread with her.”

Van Gogh struggled to support himself, but he was generous to a fault.

And about that suicide, Havlicek says that there is strong evidence that some boys were target shooting nearby and accidentally hit him. That he would not accuse them was entirely in line with his character. “He had a very sacrificial aspect to his personality. There were several times in his life when he took the blame for someone else.”

He loved Christ enormously at the end of his life,” Havlicek says. “He said Christ alone among all the magi and wise men offered men eternal life. In spite of a broken life, something glorious emerged.”

Vincent van Gogh’s Unappreciated

Journey with Christ

By Mark Ellis

[click to read]

A record 1.2 million visitors came to the giant retrospective of Van Gogh’s work in Amsterdam in 1990, which coincided with the 100th anniversary of the Dutch post-Impressionist’s death. What visitors did not see at that major exhibition were van Gogh’s Christian-themed paintings, which were left in the basement of the museum. (read more)

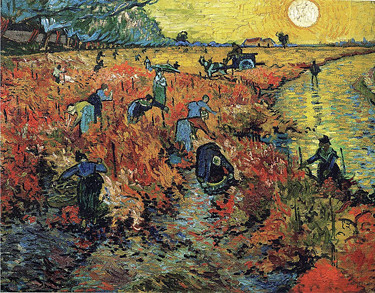

The Red Vineyards near Arles is an oil painting by the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh, executed on a privately primed Toile de 30 piece of burlap in early November 1888. It is reported to be the only piece sold by the artist while he was alive. Savhanna Herndon

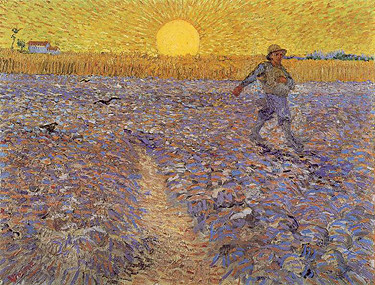

“I don’t hide from you that I don’t detest the countryside — having been brought up there, snatches of memories from past times, yearnings for that infinite of which the Sower, the sheaf, are the symbols, still enchant me as before.” (Letter 628 to his friend and painter Émile Bernard, on or about June 19, 1888).

Vincent Van Gogh, Le semeur (The Sower), Mid-June 1888. Oil on canvas, 64 x 80,5 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum,The Netherlands

Blue Spruce in Snow. Photo by Bob Kirchman

A Case for Vision IX

© 2017 The Kirchman Studio.

So why do nations fail? While a case can be made for institutional integrity, it is also clear that simply transplanting working institutions (such as the U. S. Constitution) into other societies does not necessarily guarantee success. Post-Colonial Africa testifies starkly to this, as do the wreckages of a succession of Socialist Utopia/Dystopias. If better institutions can be constructed, what are they to be made of? Acemoglu and Robinson argue for good institutions, but cannot tell us what the foundations should be. Even those who would argue that the "American" solution is the right one need to confont the reality of America today. America is in Decline. As her leaders saddle her with $17 Trillion in debt, she becomes increasingly weaker as an agent for providing for the basic security of the society. Her leaders are content to entrust our energy production to unfriendly regimes in the Middle-East, our financial and manufacturing security to unfriendly regimes in Asia and our physical security to a despot-heavy United Nations. How did we get to this point? In this conclusion to the series: A Case for Vision, we will look at some possible reasons.

As America grew increasingly secure in its prosperity, it turned its energies increasingly towards a 'consumer mentality.' Note that this is in stark contrast to the earlier mindset that America was to be a blessing to the rest of the world. The drive to send missionaries, provide clean water and cure disease took a back seat to building bigger houses and bigger televisions. Now we could outsource our manufacturing, enjoying more and cheaper goods. No longer would we have to live next to 'dirty' old factories. They could be converted into trendy botiques, lofts and coffee shops. Sadly, those jobs they created went away too! No worry!, everyone can go to college now. The problem is that the Professional sector grows only insofar as it is the supportive branch of the creation of real productivity. No problem. After college you can work/hang out in the trendy coffee shop. Gratification became a larger motivating force than the securing of Faith and Freedom. The Mall and the Multiplex Theater replaced the church and the armory at the center of the commons. Manufacturing centers could be re-purposed as shopping areas too. Religion diminished as a force for living everyday life, becoming an inspirational hour for refreshment rather than a challenge to be lived throughout the week. Hillary Clinton carefully crafted her own description of Religious Freedom to narrowly define it as the 'private practice of Faith.' Her description actually perscribes its exclusion from the public square! [1.]

Next came a sense of 'entitlement.' How else do you explain unmarried Georgetown University student Sandra Fluke DEMANDING that her school, a Faith institution run by the Jesuits, provide HER with recreational contraceptives? [2.] That she was invited to speak at the Democrat Convention and now is exploring a run for Congress speaks volumes to this new sense of 'entitlement!' There is something fundamentally wrong here... far more than the economic reality that she, as a law student, can anticipate far more income than I will ever see. She does not NEED Georgetown University to provide her with recreational contraceptives. The real travesty is that while the church is being told that it has no place in the commons, those in the commons are all to eager to place such limitations and demands on the house of Faith! A major retailer, a major furniture manufacturer and a chicken sandwich restaurant who seek to live their faith in the marketplace are all under attack. This is not an accident. The inclination of mankind towards morality has been repackaged in electric cars, cloth grocery bags and tilting at the windmill of 'Global Warming.' Stewardship of the earth, a noble thing in and of itself, can attain the status of civil Religion. Traditional Religion can get out of the way of our pursuit of Hedonism. Why should we cry out to G-d if we can make government our provider?

Finally, there is a wrongly placed national pride. This is the arrogant assertion that we somehow no longer need to rely on Divine Providence, humbly petitioning Heaven for our daily bread. We can do it all ourselves if we somehow correctly organize the commons. Thus we eschew the functions of Faith and Defense rightly performed in the commons as the commons takes upon itself to do the work of G-d! But what is the result? May I suggest it is nothing but a high-tech serfdom. Because 'we' can change the climate, we will do so by strangling the very engines of industry and ingenuity that have actually improved man's stewardship of the world (actually we've simply placed our manufacturing offshore. Our 'clean' Priuses receiving toxic batteries from a Chinese factory that would not meet the standards of our own EPA). [3.] We come to the conclusion that 'we' must alone end Acquired Immune Deficiency and balance the temperature of the planet. We will pay carbon taxes to despot regimes while stifling the energy production that will free us to advance to the next generation of propulsion! We forget the wisdom of Samuel Morse, who telegraphed: "What hath G-d Wrought?" upon the successful operation of the telegraph. We forget humility.

And yet, if you are reading this, you might realize that we might indeed pursue a better course. We might look to Bless future generations rather than feather our own nests. We might pursue our science with humble faith as opposed to arrogance, looking to a G-d who I believe is all too eager to reveal new secrets to trustworthy men and women. We might, as we realize the roots of our prosperity, seek to share those roots with our fellow man. We will not kick against Constitutions that limit institutions, seeing that the limitless resource of Divine Revelation can indeed fuel our aspirations. What drew me to Asmus and Gruden's work was their optimism in presenting a universally implementable strategy for improving the human condition. What compelled me to write this series was the burning sense that I was holding in my hands a map, if you will, showing the location of treasure far greater than the Count of Monte Cristo's map to the lost treasure of Sparta. Like the old priest, I want to press it into the hands of someone who will use it for good.

Spring Crocus. Photo by Bob Kirchman.