Volume XVIII, Issue I: January, 2020

Blue Ridge Roots, The William J. Carter Farm

Photos by Bob Kirchman

Imagine a family with ten children living in this little house in 1890.

Originally a land grant from the state of Virginia to encourage settlement in the Western part of the state, the farm eventually was the property of William J, Carter. William was born about 1837. He was the son of Thomas Carter and Anna Blacker. He passed away in 1922. The William J. Carter farm is located on the Blue Ridge Parkway at Mile 5.8. The buildings are not original but have been reconstructed on the site to reflect what was probably there in 1890.

Barn.

Chicken Coop.

Root Cellar.

Spring House.

Bear-proof pig pen.

A harrow made from native wood.

Lye hopper.

Counter-weighted gate.

Scarecrow.

Our Magical Mountains

Photos by Carrie Austin Eheart

In the series: “A Town Called Alice,” a character says of the Australian Outback: “A lot of people come out here to paint this place. The only one who got it right was an ‘Abo’ (Aborigine), because he was painting his own land!” That is why these photos of our Blue Ridge Mountains by Carrie Austin Eheart are so beautiful. She is capturing visions of her own land.

As a child, I seem to remember thinking of the Blue Ridge almost as a cardboard cutout against the sky, seen from my grandmother’s house. Later I would explore them, finding that they held many secret coves and magical streams where native trout glided by as you sat by their banks. Then I would come to understand Davy Crockett’s (yes, the REAL Davy Crockett wrote this) poem about the Appalachians:

Farewell to the mountains

Whose mazes to me

More beautiful far

Than Eden could be.

The home I redeemed

From the savage and wild;

The home I have loved

As a father his child.

The wife of my bosom,

Farewell to ye all.

In the land of the stranger,

I rise or I fall.

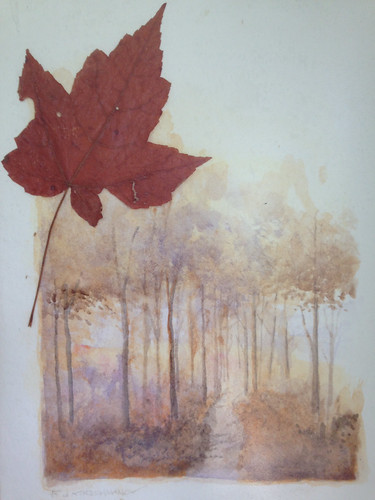

But it was in North Georgia, when I was at a conference of architectural illustrators up in the mountains around Brasstown Bald that a group of us set out to paint en plein air. Unfortunately for most of the participants, the day was foggy, overcast and drizzly. I remember sitting on a fallen log, struggling to paint. I thought I could hear the voices of those who loved this land in the past. I was moved by that but was most frustrated by my painting.

When I returned to my room, I took a fine brush and crisped up some of the tree trunks. That is how my painting “Cherokee Portal” came to be. My Cherokee colleagues love it and it is already noted that when I pass, the painting shall go to my Cherokee assistant. The grandfather in “The Homecoming” said: “You can’t own a mountain, you hold it in trust.” Perhaps it is more correct to say that the mountain owns you! This painting already belongs to Kristina because I was painting HER land! Or more correctly, I should say, I was painting the land that holds her and her family.

New Echota, Cherokee Nation Capital

Photos by Bob Kirchman

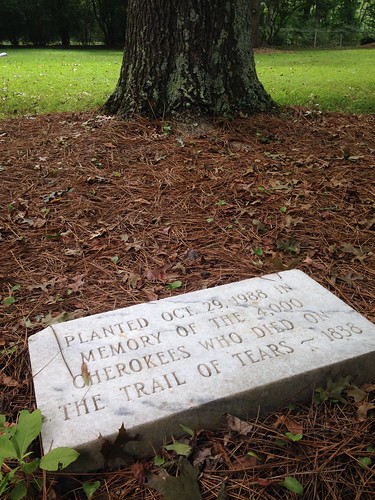

Many Cherokee farmers and their families were forced from small farms like this into stockades and eventually removed to Oklahoma in the 'Trail of Tears.'

Last Summer I traveled to Atlanta to present The Art of Design Communication and I took the opportunity to visit the capital of a great nation. Although this is last Summer’s trip, the memory is still fresh.

It is a warm August day as I travel to Atlanta Georgia through what was once the home of a great nation. Pulling off of Interstate 75, it is a short drive to the reconstructed capital of the Cherokee, New Echota. It was never a large city but it would swell to an encampment of hundreds of people when the council was in session.

The offices of the Cherokee Nation's Phoenix, a newspaper published in both English and Cherokee.

The Phoenix printing press.

Sequoyah's 'Talking Leaves.'

The Gift of Language

How Sequoyah Gave His People Written Words

Perhaps the most remarkable man who has ever lived on Georgia soil was neither a politician, nor a soldier, nor an ecclesiastic, nor a scholar, but merely a Cherokee Indian of mixed blood. And strange to say, this Indian acquired permanent fame, neither expecting or seeking it." -- H. A. Scomp, Emory College

He was hardly someone you would predict would create such a significant contribution to his nation. George Gist was born to a Cherokee mother, Wu-teh, a member of the Paint Clan, and Nathanial Gist, an English fur trader near the village of Tushkeegee on the Tennessee River. The year was around 1760 but no one knows for sure. Learning the ways of the Cherokee, young George became a trapper and a fur trader himself. He would probably have lived out his days as a man of the forest, but he suffered a hunting accident (or possibly succumbed to a crippling disease, depending on which version of his story you read), but the young man was permanently disabled, unable to earn his living by the skills he had been taught in childhood.

George Gist developed a talent for metal working. He learned to be a blacksmith and silversmith. His disability became both a source of ridicule (Sequoyah means "pig's foot" in Cherokee) and a spur to greater things. The man was a good learner and became a competent craftsman. A man who purchased one of his pieces suggested that he sign his work, but he was unable to. He could not write! And here as well his story might have ended, but events in the greater world were to spur him to his greatest work. Sequoyah married a Cherokee woman and raised a family. They moved to Cherokee County in Georgia where George learned how to write his name from a local farmer. Later he joined other Cherokees who fought under Andrew Jackson against England in the War of 1812. Though he never learned to read or write English, Sequoyah was fascinated by the white man's ability to create "talking leaves" by making marks on paper.

As early as 1809, Sequoyah was exploring the creation of a Cherokee alphabet. Though scholars believe there may have once been a written Cherokee language that was later forgotten, there was no written Cherokee language when Sequoyah was a youth. People suspected that the white man's words "moved around on the paper," and the time was right for Cherokee to be able to read things for themselves. Cherokee soldiers could not write letters home, read military orders for themselves, or record events they wished to remember. When he returned home from the war, he worked in earnest on a phonetic alphabet of 86 letters to write the Cherokee Language. Sequoyah became something of a recluse. His friends and family ridiculed him. Some said he was insane or practicing witchcraft. Moving West to Arkansas, he continued his great work.

He found that his young daughter Ayoka could easily learn to use the syllabary and demonstrated this to his cousin, George Lowrey, who encouraged him to demonstrate the use of the syllabary to the public. In a Cherokee court case in Chattooga, he read an argument about a boundary line from a piece of paper. In 1821 the Cherokee Nation officially adopted Sequoya's alphabet and within a matter of months thousands of Cherokee learned to read and write! In 1824 the Cherokee National Council at New Echota, Georgia presented him with a silver medal. Sequoyah proudly wore it for the rest of his life. He was given a $300 annuity and his widow continued to receive it after he died.

By 1825 the Cherokee had the Bible in their own language along with hymnals and all sorts of educational materials. There was even a large group of Moravian Cherokee. Legal documents and books of every kind were available, all translated into the Cherokee Language. In 1827 The Cherokee National Council funded the printing of Tsa la gi Tsu lehesanunhi," the Cherokee Phoenix. It was the first Native American newspaper printed in the United States. It was produced in the Cherokee Capital, New Echota on a press shipped there from Boston. The paper had parallel columns in Cherokee and English, printed side by side.

Sadly, the discovery of gold in North Georgia, unscrupulous men and treachery in treaty would lead to the removal of most of the Eastern nation. Sequoyah moved to Oklahoma were he served as an envoy to Washington D.C. to assist the displaced Eastern Cherokees. He continued to serve his people as a diplomat and a statesman. Well into his eighties, he traveled West again, looking for a band of Cherokees who were said to have moved to Mexico. He took ill and died in 1843 and the location of his grave remains unknown to this day. Two species of giant redwood trees have been named in his honor, as has Sequoia National Park in California. He gave his people the gift of literacy. His contribution is unique, as he, an uneducated, seemingly undistinguished individual, created a totally new system of writing for his beloved nation.

Remembering History

After the residents of New Echota were taken away in the ‘Trail of Tears,’ the town itself disappeared. The state of Georgia had held a lottery to redistribute the land and it became farmland. The houses were taken down, save for that of Samuel Worcester, missionary to the Cherokee and Postmaster. It survived in other hands. The trees that shaded the streets were cut down. The town itself was but a memory.

In the 1960’s a group of people came together who thought it important to remember the great nation that had once occupied North Georgia. They persuaded the state of Georgia to create the present park at New Echota. The principle buildings have been reconstructed and stand in silent monument to those who were ripped from their land a century before.

Forest, New Echota

Although the area surrounding New Echota, the Cherokee Capital, was cleared for farmland after the Cherokee Removal, the forest has returned.

Photo by Bob Kirchman.

New Echota Houses of Government

Reconstructed Supreme Courthouse. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

In 1825 New Echota was officially designated as the Cherokee Capital. The Council had been meeting in New Town (as New Echota was originally known), on the headwaters of the Oostanaula River, since 1819 and the Council house was built in 1822. Beginning in 1823, the Cherokee Supreme Court met annually to hear cases appealed from lower district courts. The Supreme Courthouse was constructed in 1829.

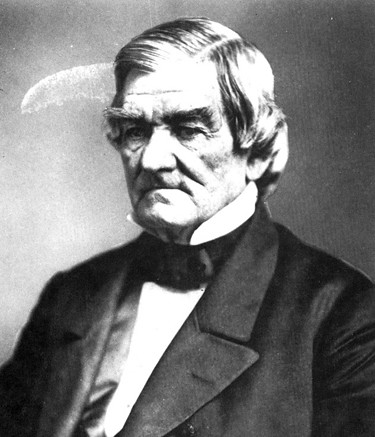

The government was set up similar to that of the United States, with a Legislative, Judicial and Executive Branch. The Council chose the Executive Branch officers, the Principle Chief, the Vice-Principal chief and the Treasurer.

Principal Chief John Ross, who's Cherokee name was Tsan-Usdi, and is also known as Koo-wi-s-gu-wi, the name of a mythological, or rare migratory bird; served in that capacity from 1828 to 1866. He led his people through the times of the Cherokee Removal and the Civil War. Although he was only 1/8 Cherokee, the son of a Scotch Father and a Cherokee mother, he was raised traditionally. The full-blooded Cherokee recognized his skills in dealing with the United States government and the settlers around them who wanted their land. He was a tireless advocate for his people, resisting the removal. His wife Quatie, mother of their five children, died on the ‘Trail of Tears.’

Council House. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Principal Chief John Ross. Archives of the State of Georgia

Cherokee Portal

Painting by Bob Kirchman

Cherokee Portal. Bob Kirchman 1998.

I painted this little watercolor twenty years ago when I went to another conference in Georgia. On that trip I was able to go off in the mountains and had time to paint. It was a rainy day and I felt in the soft subdued light and mist like I had been transported to another time.

Stone Mountain, near present day Atlanta, was sacred to the Cherokees and the Creeks and the two nations used it as a meeting place.

New Echota, Cherokee Phoenix

1828 Edition of the Cherokee Phoenix.

Sometime around 1809 a mixed-blood Cherokee known as Sequoyah began developing a written Cherokee language. In 1821 his work was complete. The language had 86 characters and was adopted by the Cherokee Council in 1826. In 1827 Rev. Samuel Worcester helped to establish the Phoenix Printing Office. Using specially forged type, the newspaper had side by side columns of English and Cherokee. It was distributed throughout the Cherokee Nation, the United States and even parts of Europe. In addition to the newspaper, the press also produced a Cherokee Bible, a hymnal and even a novel.

This simple printing office managed an international distribution of the Phoenix. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

New Echota, Vann Tavern

Photos by Bob Kirchman

Vann Tavern was built around 1805 by James Vann. He was a wealthy Cherokee plantation owner. The Nineteenth Century tavern served travelers as restaurant, store and inn. An outside stair led to guest quarters upstairs and the window on the porch served as a ‘takeout window’ for those the innkeeper would not allow inside. Although this particular building was moved to New Echota from Forsyth County, Georgia, it is representative of the tavern that would likely have stood here.

Interior of Vann Tavern.

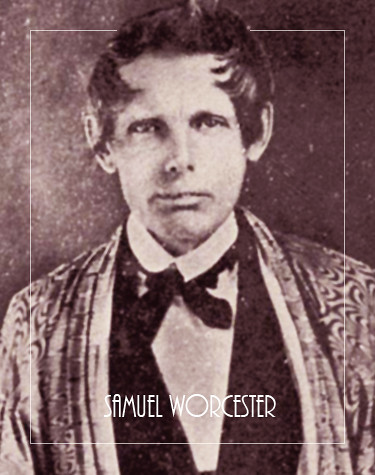

Samuel Worcester. Archives of the State of Georgia.

Samuel Worcester

A Life of Service and Sacrifice

In 1828 the Reverend Samuel A. Worcester built his home among the Cherokee at New Echota. Working with Elias Boudinot, Worcester translated parts of the Bible and many hymns into Cherokee. The press at New Echota which also produced the Phoenix printed many of these works. Worcester planted a church at New Echota and also started a school. He served as the town’s postmaster.

As the state of Georgia passed laws that were oppressive to the Cherokee Nation, Worcester refused to obtain the permit the state required for a white person to live in the Cherokee lands. In 1831 he was arrested and sent to prison by Georgia officials.

His case was appealed to the United States Supreme Court. In Worcester v. Georgia, Worcester and the Cherokees won. The state of Georgia, however, continued to annex Cherokee land. In 1832 Worcester and his family were forced from the house when a white Georgian obtained title to it in the 1832 land lottery conducted by the state.

Samuel Worcester moved to Oklahoma where he continued to serve and advocate for the Cherokee Nation. As the town of New Echota disappeared and became farmland, his house continued in use by different families until 1958 when it was restored as a historic home.

The restored home of Samuel Worcester in New Echota. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Bears in Shenandoah Park

Ursus Americanus, Virginia's Largest Mammal

Photos by Bob Kirchman.

The Boy Who Sailed Around the World

[click to read]

Robin Lee Graham's Incredible Journey

Sixteen year old Robin Graham circumnavigated the globe.

On his sixteenth birthday, March 5, 1965, Robin Lee Graham said to his mother and father: "Know what I'd really like a boat of my own that I could sail to the South Pacific islands."

Most parents, upon hearing such talk, would dismiss it as impetuosity, but four and a half months later Robin stepped aboard his own 24 foot fiberglass sloop, Dove, a light displacement craft usually regarded as a day-sailor, and shoved off from Los Angeles for a shakedown cruise to Hawaii, a passage that took 22 1/2 days and was a piece of cake all the way.

Alone except for a pair of kittens, he entertained himself most of the way with his guitar and folk tunes, navigating the 2,230 nautical miles with the aplomb of a veteran topgallant hand. It was so easy, in fact, that once in the islands, it seemed the most natural thing in the world just to keep going on around. At first, he hoped to find a companion to share the adventure, but few schoolboys have parents as lenient as were Robin's mother and father. Then he made up his mind to do it alone, just as had Captain Slocum back in 1895-1898. But where Slocum had made his voyage at the end of a long career at sea, Robin would be doing it at the beginning of his, and if successful he would become the youngest person ever to sail alone around the world.

So, at 11 A.M. on Tuesday morning, September 14, 1965, he said his good-byes again to his parents and departed Honolulu's Ala Wai yacht harbor. In spite of its small size, Dove was easy to manage and had been modified for ocean voyaging. There was a small inboard engine, supplemented by an outboard with a long shank. A steering vane designed and built by his father had been installed. As for Robin, although a mere callow boy, he was far from inexperienced. During 1962 and 1963, with his mother, father, and older brother, he had helped crew the family 36-foot ketch, Golden Hind, all through the Pacific islands. During that cruise, his father had taught him seamanship, celestial navigation, shipboard maintenance, and all the other skills so vital to bluewater voyaging. Robin was a good student, and along with his lessons, he acquired a deep love for the sea and sailing.

This background, then, explains why his parents were so "lenient" and understanding. Moreover, sailing around the world had been a lifelong ambition of Robin's father, but World War II and then raising a family had intervened. Robin had often heard his father talk about this, and perhaps by some psychological osmosis had assumed responsibility for fulfilling the goal.

His family had helped him prepare for the voyage, besides furnishing the boat. They had collected charts and navigation materials, food and supplies, a camera and film for recording his adventures, and a tape recorder with which to make on the spot comments.

His father, it seemed, became more obsessed with the voyage than Robin, perhaps seeing it vicariously as his own. He threw himself into the preparations and outfitting, spending most of those last hectic weeks with his son. As Robin recalled later, it was a period when he and his father were the closest in their entire lives. Along with taking care of preparations, Robin's father had also become his manager and agent, and complex arrangements were made to sell the story of his circumnavigation to publications and broadcast media, and set up lecture tours. It was going to be one circumnavigation that made money or else.

The only malfunction on the passage to Hawaii had been the vane steering. This was rebuilt by his father. He had aboard a transistor radio for news and weather and the WWVH time ticks. He later picked up a Gibson Girl war surplus emergency transmitter, which sends out an S.O.S. when cranked. He also had fishing gear, a .22 caliber pistol, and a large supply of recording tapes.(5) The newspapers prior to his departure, had called him the "Schoolboy Sailor," and he was well aware that his voyage was unique and newsworthy. His frequent long sessions with the tape recorder revealed this adolescent sense of destiny.

Leaving Hawaii with only $75 in cash, he made a perfect landfall fourteen days later at the British-owned Fanning Island,(6) only 12 miles square and 1,050 miles down course. Robin was a competent seaman, and shooting sights with a sextant on a 24-foot cork was child's play for him. When on deck, he always wore a harness with lifeline. He kept the harness on at all times, even when in the bunk below, so that all he had to do when he came up on deck was snap the lifeline to it. The only times he failed to do this on the entire voyage, he fell overboard and narrowly escaped being left behind once in the Indian Ocean and once in the Atlantic.

The further from Honolulu he got, however, the more lonely and homesick he became. He began talking almost constantly into the tape recorder. Among his stores, Robin had about 500 pieces of secondhand clothing, plus various trinkets for trading among the islands, in the naive belief that he could exist by bartering among the islands. He spent several days at Fanning, a former cable station, but now a copra plantation, and when he left he took a sack of Her Majesty's mail for posting in Pago Pago.

Only twenty miles from Tutuila, after two weeks of hard sailing, a squall buckled his mast and the lower shrouds parted. Robin felt like crying, but he lashed the wreckage to the deck and set up a jury sail. His engine could not cope with the wind and current. An airplane passed over. Robin showed a bright orange distress flag and fired flares, but was unseen. After anxious hours, he limped into Apia.

In Samoa, he received mail and supplies from home, including a spare sextant and a log spinner to replace one taken by a shark. Reluctant to set out, he decided to wait until April, when the hurricane season was over. This was a fortunate decision. On January 29, a vicious hurricane swept the islands and nearly wrecked Dove in the harbor.

On May 1, 1966, he finally departed. His only companion was Joliette, one of the kittens. The other had jumped ship. The passage to Tonga was enjoyable and now he had company in other world cruisers he had encountered, including the Kelea from Vancouver, B.C.; Corsair II from South Africa; Morea from California, Falcon from New Zealand. He was to meet the same yachts (and others)again and again at various ports. He reached Suva on Viti Levu, Fiji's main island, on July 1. He had only $23 cash, and since an airline ticket of a $100 bond was required by authorities, he had to prevail upon the American consul for a loan.

He enjoyed his stay in the Fijis more than any place he had ever been. In fact, here the voyage was nearly terminated for the first time. He had met through friends a girl named Patti Ratterree from Los Angeles another restless and curious young American who was traveling around the world on her own, stopping to work at various places and living mainly by her wits.

It was love at first sight, Robin wrote, and after weeks of an idyllic existence sailing among the tropical islands of Fiji, only Robin's firm commitments and his father's pressure could induce him to give it up and go on. So he and Patti split up, but agreed to keep in touch by mail and to meet ten months later in Darwin, or failing that, in Durban.

Leaving the Fijis alone, Robin met his father again in the New Hebrides. They spent the next few weeks together, then Robin sailed for the Solomons and his father took passage on an inter-island schooner, meeting him in Guadalcanal. His father stayed through Christmas, Robin's second so far on the voyage, and they had good times together exploring the islands, many of which had those familiar names from World War II, which his father's generation had come to know so well - Savu, Tulagi, Florida - where many of the natives still remembered the G.I.'s with fondness, never understanding why they did not return. They visited the rusted old hulks of ships and tanks, the weed-grown foxholes, finding bits of bone, pieces of rotted boots, bullet-pierced helmets. Robin was impressed by the sacrifices which his father's generation had made in those dark days. But now, he felt, this was his world.

At Honaira, Robin sold his inboard engine, which was useless. He earned additional money by renting his spare genoa to a local yacht going to New Guinea. On his eighteenth birthday, he wrote his draft board and later received a reply in Australia, telling him to check with them upon his return. He did not know then that it would be another three years before he would be home.

From the Solomons, he encountered calms and sticky hot weather, mixed with squalls and adverse currents. It took twenty-three days to cover the nine hundred miles to Port Moresby, where he spent three weeks on shore. On April 18, he departed for Darwin through Torres Strait and into the Arafura Sea, a heavily traveled shipping route. The many ships passing in the night kept him up until exhaustion drove him below. One night, while lying in the bunk, he heard a loud swish and felt something scrape the hull. He rushed up to see a large black unlighted ship disappearing into the night. He had escaped a collision by the thickness of a coat of paint. He wondered how many lonely navigators including Captain Slocum himself had near-misses, for just this reason unmarked, unlighted ships without lookouts, passing callously in the night.

Robin reached Darwin on May 4, and spent several weeks ashore, including a month working on a power station project, rigging guy wires on towers. The further Robin had sailed on his circumnavigation, the more disenchanted he had become with the idea. He would have quit back in the Fijis had it not been for his father and those firm commitments (the National Geographic magazine had already started running a series on his voyage). When his father first heard about Patti, he was somewhat furious especially when Patti showed up in Darwin. From that point on, Robin's relations with his father were strained at best, and may have contributed to his parents' breaking up their marriage. When his father first met Patti, he obviously considered her something of a tramp and an obstacle to completion of the round-the-world voyage. At Darwin, too, a National Geographic photographer showed up with his equipment and some firm instructions to get some usable material for future issues. Apparently, the principal sponsors of the adventure were also having second thoughts.

Before leaving Darwin, Robin and Patti agreed to meet in Durban, and this was probably all that kept the lad going during the next leg of the circumnavigation, across the Indian Ocean via Keeling-Cocos, Mauritius, and Reunion.

On July 6, 1967, he sailed again, his first landfall to be Keeling-Cocos, the family-owned autocracy and fiefedom in the Indian Ocean. It had been from Thursday Island to Cocos that Captain Slocum made his famous run of 2,700 miles in 23 days without touching the helm. Robin made the 1,900 miles from Darwin to Cocos in 18 days almost exactly the same speed as Slocum had recorded in the Spray. This was a pleasant sail, with little to do but fill his hours with sewing sails, making rope belts, taking photos of himself with a tripping line, and dictating into the recorder.

From Cocos to Mauritius, some 2,400 miles, it was usually all downwind, and once you leap off from Cocos there is no turning back. But only 18 hours out, running through a line of Squalls, Dove was dismasted again. Rushing out on deck to save what he could, Robin was thrown overboard as the boat lurched. It was the first time he had not worn his lifeline. By sheer fate, another lurch brought the boat within reach. He caught hold of the rail and climbed back aboard. Coming out of the warm water into the cold rainy wind, he was overcome by chills. He went below to wait daylight. He had 2,300 miles to go to reach Mauritius, and no chance to get back to Cocos. When daylight came, he was able to rig a small square sail from a bedsheet and set it on the forestay. This ripped out in the 25-knot winds, so he set an old yellow awning which he had to patch with a tea towel and an extra shirt. In this manner, he limped along through heavy seas and continued squalls for twenty-four days, averaging almost one hundred miles a day, and reaching his destination almost at his original E.T.A!

At Port Louis, he again met fellow ocean vagabonds the Shireen and Mother of Pearl from England; the Edward Bear and Bona Dea from New Zealand; Corsair II from South Africa, and the Ohra from Australia. Here Robin stayed to enjoy the local hospitality and to make repairs. The National Geographic Society shipped out a new aluminum mast from California by Quantas.

The next stop was Reunion, a beautiful but expensive place. After a short stay, he left in company with the Bona Dea and the Ohra for Durban. Three days later came the most violent weather of the entire voyage, with mountainous seas. For seventeen days, Dove was battered and pummeled, at times threatening to roll over and at other times to pitchpole. It was too unsafe to be on deck, so Robin spent his time in the bunk reading books and periodically talking into the tape recorder. Anything loose in the cabin soon became a flying missile. Doors were smashed, water ruined his flour and dry provisions, his tape recorder took a soaking. Robin held on and prayed for calmer seas, which came one morning with a gentle northeast breeze. Soon after he saw the coast of Africa and then was caught up in the heavy ship traffic caused by the closing of Suez. Then he reached Durban, crossed the bar, and tied up to the mooring at the Royal Natal Yacht Club.

It was now spring in South Africa, and Robin had completed half his circumnavigation. And Patti was waiting here for him. They had decided to get married, but Robin was still a minor. He had to get permission from his parents. It finally came, and Patti officially became Mrs. Robin Lee Graham. They bought a motorbike which they named Elsa, and took off on a honeymoon to Johannesburg and the Transvaal. They had a wonderful time, one that grew more difficult to end the longer they waited.

Dove had to be almost entirely rebuilt and beefed up. The deck had been coming loose from the hull, several bulkheads were cracked, and there were signs of general deterioration. After much soul searching and pressure from parents and sponsors he got underway at last. The difFicult passage around the bight of Africa was the worst of the entire voyage. He made it by running close to shore and putting in frequently at available havens, beset by head winds and adverse currents. This was better, however, than the mountainous seas out beyond the 100-fathom line. With increasing exhaustion, he ducked into East London, Port Elizabeth, Plettenbergbaai, Knysna, Stilbaai, Struisbaai, and Gordon's Bay. At Port Elizabeth, he nearly lost Dove when the anchor dragged. The deck pulled away from the hull again, and opened up a seam which leaked. There were signs of rot in the plywood, and the layers of fiberglass were separating.

He confided in his secret journal that he had planned to scuttle the vessel here along this lonely coast and claim an accident, so he could quit this voyage and be with Patti. But something kept him going. At Cape Town, more repairs were necessary. This gave Robin and Patti another two months together, most of which they spent at a delightful old boardinghouse called Thelma's. They made many friends among the older people living there. One couple in particular they became fond of were a man about eighty-five and his bride, seventy-five, who had been married about five years and acted like newlyweds. Their happiness made Robin and Patti feel good and right.

From Cape Town, the next leg would be five thousand nautical miles to Surinam with a stop at Ascension. Robin acquired two more little kittens, Fili and Kili, which he named after the youngest dwarfs in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit. While Robin sailed on Dove, Patti would be on an Italian line, the Europa, bound for Barcelona. They made arrangements with the captain to keep a radiotelephone schedule, which was only partly successful, but did help Robin's morale.

The loneliness was the worst thing about the Atlantic crossing. When the weather was good, he worked positions, read books, sewed sails, listened to the battery radio, bathed, cooked, played with the kittens, talked into the recorder. In his log, on July 27, 1968, he recorded the third anniversary of his departure. It began to get to him. One day he found a Japanese float with two crabs and some barnacles clinging to it. Knowing the crabs would die in the open sea, he made a raft of plastic foam and sent them adrift in this. He even put the gooseneck barnacles on the raft so the crabs would have something to eat.

He sighted St. Helena but did not land. On August 23, he dropped anchor at Clarence Bay, Ascension, where he was welcomed by PanAm crews manning the tracking station. He passed Fernando de Noronha on the twenty-first, and picked up the coastal current off South America. On the twenty-fifth, he crossed the equator for the second time. On the thirty-first, he made the lightship at the mouth of the Surinam River, entered and went upstream to Paramaribo. The Atlantic crossing had been the worst of all, from the standpoint of mental and spiritual exhaustion. Moreover, he had fallen overboard again and this time barely made it back aboard as Dove sailed on. The sloop was literally coming apart, and each spell of bad weather increased his apprehension. Finally, Patti was not there when he arrived, and did not show up for several weeks. Meanwhile, Robin toured the back country with local officials and National Geographic Society staffers. When Patti arrived, she was flown in to the jungle to meet him, and they spent three weeks together.

At this point, Graham knew he could not go on. He told the National Geographic people and his parents and other sponsors. The NGS sent a top editor down to talk to him. His mother came out from California to see him and meet Patti for the first time. Robin put Dove up for sale in the West Indies.

Finally, a compromise was worked out. Dove was replaced by a new 33-foot sloop, manufactured by Allied Boat Company, Inc., of Catskill, New York. There were more advances from articles to be published. The couple found a nice apartment on the leeward shore of the Barbados and settled down to housekeeping for a while. They toured the islands by motorbike, and Robin obtained part-time work.

The sleek new 33-footer was named The Return of Dove. It was delivered in Florida. He and Patti picked it up and sailed to the Virgin Islands, where little Dove was finally sold. The new boat had a depth sounder, a radiotelephone, a kerosene stove (Robin found alcohol unsuited for ocean cruising and as Eric Hiscock wrote, it is cheaper to buy bonded whisky in many places, than stove alcohol).

As soon as the hurricane season was over, the new boat was hauled and painted, and refrigeration installed. On November 21, Patti left on the S.S. Lurline for Panama. Robin got underway again. At Porvenir, they met again, explored the San Blas Islands, and motored into Cristobal, where they tied up at the yacht club.

Over the Christmas holidays, they visited friends, fixed up The Return of Dove a little, and on January 17, the pilot came aboard and the canal transit was made. At the Pacific end, they stopped briefly at Balboa, then sailed for the offshore islands for a couple weeks alone.

On Friday, January 30, Robin headed again to sea, and on February 7,he made San Cristobal in the Galapagos Islands. Patti flew to the airport at Baltra with her father and stepmother, Allan and Ann Ratterree. Another idyllic vacation was spent here.

On March 23, Robin departed on the long run uphill to Los Angeles. He now had 2,600 miles to go against some of the worst conditions of the voyage adverse winds and currents, coupled with frequent calms. But now, however, he had a working auxiliary engine to get through the calms, he had two-way radio, and even ice cubes. In spite of this, the little mishaps became major annoyances, and he at times gave himself over to periods of violent frustration, during which he would hurl things against the bulkhead and fuss over his inability to untie a knot in a line. The going was agonizingly slow, sometimes making only thirty miles a day. On April 15, he heard American ships on the radio. The next day, he raised the fishing vessel Jinita out of San Diego, which relayed a message to Patti's father in Long Beach. The next day the engine would not start and he had no more electric power.

The trouble was simple. He had forgotten to open the engine exhaust. The Jinita called him and reported that she was not able to reach Al Ratterree, while another boat, the Olympia, broke in to say she could relay and deliver the message.

Then Kili the cat began to go crazy, alternating between viciousness and limp whining. Everyone on Dove was getting channel fever.

The uphill beat was increasingly rough. On the twenty-fifth day, however, he was only 250 miles from Long Beach. On the twenty-eighth, he was about 100 miles away. On the twenty-ninth, he passed San Clemente Island. For the first time, the prospect of actually going home became a reality.

His first impression of the California coastline was the stench of land and civilization. It had a raw, pungent smell of hot asphalt and concrete.

At 7 A.M., on April 30, 1970, Robin sailed in between the breakwaters of Los Angeles harbor, which he had left 1,739 days before in the first Dove. He had traveled 30,600 sea miles. He was five years older, now a mature young man, with a wife (pregnant) and his whole life ahead of him.

After the enthusiastic welcome by friends, family, and the television cameras, he set about to settle the draft board problem, and to enter Stanford University in his native state. When the excitement had subsided, he and Patti enrolled at Stanford. Until they could sell The Return of Dove, they had little money, but were able to find a patched-up secondhand mail van and rent a one-room cabin in the hills near the campus. Robin worked at odd jobs around the campus. At one point, they had to live on fruit and vegetables Robin picked up behind a supermarket.

Robin had planned to get an engineering degree with architecture as his goal. But the young couple, after roaming the world, found they had nothing in common with others their age. At the most critical point in their lives, they had acquired experiences and attitudes that the average youth is never exposed to. Robin noted in his journals how sad it seemed to him to see some students coming to college right out of high school, ready to believe anything told them by cynical professors. He remembered one professor in particular, a Maoist, who preached passionately for bloody revolution in class, and was applauded loudly by those students who owned the most expensive Porsches and Jags.

That first semester at Stanford seemed longer to Robin than the first two years at sea. After one particular trying day in which he had to listen to the Maoist professor ranting about his new society in which "everyone would be equal and thieves would be treated in a hospital," Robin and Patti stayed awake all night discussing what to do. The next morning, they decided it was time to move on.

The Return of Dove finally sold, and as soon as the papers were signed and they had the money, they headed their battered mail van toward the northwest. They had discussed going to Canada to settle, but did not really want to lose their American citizenship. The next best thing seemed to be Montana, and it was there that they found what they wanted on a rugged 160-acre timbered homesite in the mountains near Kalispell. The nearest neighbors were three miles away. In the woods around them, they could find the fresh signs of deer, elk, and bear. They started by building a lean-to cabin from scrap timber. They cleared a garden patch and planted fruit trees. For the next six weeks, they stayed in the village where Robin took lessons in logging and forestry. With a mail order course, they planned to help educate their daughter, Quimby, and themselves, and meanwhile they would build a new and simple life style based on understanding and enjoying the natural world. The neighbors brought them some home-made cheese, wine, and bread. They stocked their cabin for the coming winter. Robin went about learning how to kill a deer or elk for their winter meat supply.

The thought of Patti and Quimby standing in the doorway of the cabin, as he came up the trail with a deer over his shoulders, brought back the words he had copied into his notebook from the gravestone of Robert Louis Stevenson in Samoa:

Home is the sailor, home from the sea, And the hunter home from the hill. (read more)

[1.] Don Holm's 'The Circumnavigators' , ch. 34

Calming the Storm Within

[click to read]

Epilogue to the Great Voyage

Snow swirls past the lighted windows of a log home set deep in the conifer forests surrounding Kalispell, Mont. (pop. 11,890). Inside, Robin Lee Graham sits with his wife, Patti, daughter Quimby, 18, and son Ben, 11, studying a question from Global Pursuit Geography is something Robin knows better than most. Not formally—a high school dropout, he never excelled academically. But in 1965, as a scrawny boy of 16, Graham sailed out of San Pedro harbor in a 24-foot sailboat called Dove to begin a voyage that would make him famous. It was five years—and 30,600 nautical miles—before he returned, the youngest person ever to sail alone around the world. (read more)

Return from the Brink

[click to read]

For a kid who had dropped out of school and escaped to sea, Robin Graham was woefully under-prepared for life back on land. He developed a deep depression, which overran him with all the attendant issues of alcohol and drug addiction. To his immense credit Robin was able to climb out of these depths with the aid of Patti and their newfound Christian faith. They built a log cabin in Kalispell, Montana, surviving their first winter and a badly-acted movie about his adventures, which came out in 1974. They still live there to this day and have raised a young family and delight in their anonymity. (read more)

The Sailor at Home

[click to read]

Fifty years ago, Robin Lee Graham made international headlines when he became the youngest person to ever sail solo around the world. Today, he and his wife Patti live a quiet life on the shores of Flathead Lake. (read more)

Volume XVIII, Issue Ie

Apprehending the Transcendent

Roger Scruton and Jordan Peterson

Epiphany, Another Forgotten Season

Celebrated by the Western Church on January 6th, Epiphany celebrates the revelation of Christ to the Nations, as pictured by the visitation of the Magi. Portrayed as three Eastern kings astride camels, they follow the Christmas star to worship the newborn King. Here is a profound telling of truth that is often lost in its cultural wrappings. If ever there was a celebration needed for today, it is Epiphany!

The biblical identification for these pilgrims is Magi. The Magi are an interesting group in temselves, originating in a hereditary priesthood of the Medes (the ancestors of modern day Kurds). They were installed as religious leaders and policy advisors to the Persian court by Darius and here they actually make their first appearance in Holy Writ. Daniel, carried into exile from the fallen kingdom of Judea, is assigned to this group when he surpasses the rest of them in his service to the king. Daniel correctly fortold the return of the exiles seventy years in the future.

Though he served a secular king and kingdom, Daniel never lost his connection to G-d and Jerusalem. His quarters had a window facing Jerusalem and he was 'busted' for praying when the king decreed that all his citizens bow only to him. Daniel's deliverance from this decree's punishment, by a Divine intervention, is an often told story by people of Faith. What must be conjectured, however, is the influence this man of Faith might have had on his fellow wizards.

Daniel never returned to Jerusalem, though he never forgot her. He grew old and died as a stranger in a strange land. Though he walked the halls of power in Persia, his citizenship remained in the Land of Promise. His book ends with descriptions of things far into the future, and is silent about the later life of Daniel himself. One might safely assume that he remained in the company of the Magi and continued to serve the Persian court.

A young spiritually minded person would have sought out men like Daniel as mentors. Thus it is highly likely that the hope of the coming King was wrapped into the fabric of Daniel's life and work in such a way that his apprentices would preserve it. Many years later it propelled some of them on a long and perilous journey to find that King. There is no Scriptural reference saying there were only three. That may be an assumption based on the mention of three specific gifts they brought; Gold Frankincense and Myrr.

And what did they find? A Child and his mother, ordinary in their appearance perhaps, but marked by Heavenly purpose! Picture the scene, if you will, of mighty clerics, who direct the affairs of empire by their counsel bowing before a woman and an infant!

Epiphany compels us to wrap our minds and hearts around ancient truth and promise. Epiphany compels us to fight the myopia of contemporary culture and look for the Hand of the Divine! Epiphany compels us to awaken from our slumber and if we hear the voice of G-d, to LISTEN! Epiphany is that discovery so wonderful it is a sin to conceal it. It is a truth that carries a blessing for ALL who will hear it and heed it.

So, as the world around us marks the beginning of a new year and marks down the merchandise of Christmas past, it is really time to continue unwrapping the wonder of G-d's redemptive relationship with His children. Old truths must be pondered, but the promise we find there demands action. The voice of G-d must be answered. History, you see, is not some endless cycle. It leads us on a journey to find a specific destination. The voice of the Divine speaks of far more than some warm feeling of self-actualization. It calls us to participate in the ushering in of a Greater Kingdom!

C. S. Lewis captured the hope and the message so well in this thought from "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe:"

When Adam’s flesh and Adam’s bone,

Sit at Cair Paravel in throne,

The evil time will be over and done."

Spoken to four rather ordinary children, the extaordinary hope of Aslan's rule creates a feeling of thrilled anticipation. Does the knowledge of the unfulfilled prophecies of G-d's Eternal Kingdom create in us today that feeling as well?

Epiphany's Meaning for Today

Around the world, the hope of Christ's Eternal Kingdom fires the passion of Christians in diverse and difficult situations. Coptic Christians in Egypt share this hope with hidden house church groups in China and North Korea. In Nigeria the faithful watch their churches destroyed, knowing that an Eternal Jerusalem awaits them.

Twelve men hiding in an upper room were propelled outward one Pentecost long ago to share that hope. These reluctant witnesses found themselves empowered by the Holy Spirit as they went. At first glance, history seems to tell us that the church eventually divided into many factions... today many at the tips of these branches hold tight to their distinctives, but miss the branching and rooting of a great tree. Today there are many distinctive groups within Christianity, but the essential message has survived. Essential truth has indeed flowed like the lifeblood of this great tree.

Adoration of the Magi, (1600) Jan Brueghel the Elder.

The Epiphany, It is Important

The traditional celebration of Christmas lasts for twelve days. It begins on Christmas Day with the celebration of the birth of the Redeemer and ends on Epiphany, which celebrates Christ's revelation to the gentiles. The MAGI, or the Wise Men came from Persia seeking a prophesied King. It is very likely that these were men who had studied the writings of Daniel and now saw the signs of the fulfillment of things he had written: "And the kingdom and dominion, and the greatness of the kingdom under the whole heaven, shall be given to the people of the saints of the most High, whose kingdom is an everlasting kingdom, and all dominions shall serve and obey him." -- Daniel 7: 27

The revelation of Christ to the Gentiles also fulfills a promise made to Abraham: "By myself have I sworn, saith the Lord, for because thou hast done this thing, and hast not withheld thy son, thine only son:

That in blessing I will bless thee, and in multiplying I will multiply thy seed as the stars of the heaven, and as the sand which is upon the sea shore; and thy seed shall possess the gate of his enemies;

And in thy seed shall all the nations of the earth be blessed; because thou hast obeyed my voice." -- Genesis 22:16-18

Paolo Veronese (1528 - 1588)

Nativity, Epiphany and Baptism

Over the last few weeks we’ve celebrated three great feasts of the Church; namely the Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Epiphany and the Baptism of Christ. These are three great feasts of the revelation of God to man in Christ Jesus and to begin to understand something of their message we must first look at their evolution.

It’s a little known fact that these three great feasts celebrated on the 25th of December, the 6th of January and the first Sunday after the 6th of January (or if you are in England, the 25th of December, a movable Sunday between the 2nd and 8th of January and the first Sunday after the Epiphany unless the Epiphany falls on the 7th or 8th in which case the Baptism of the Lord, as it was this year, is bumped to a Monday: Sometimes being English is more complicated than it’s worth!) were originally all celebrated on the 6th of January, an ancient date first mentioned in the 4th century but very likely to have been celebrated much earlier than this.

The original feast was hugely rich and celebrated the revelation of the Creator to the creation in Christ Jesus by looking at the birth of Jesus, the adoration of the Magi, the Baptism of Christ and the wedding feast at Cana. In the 4th century the Nativity of Christ was separated from these other remembrances of the incarnation by the Church of Rome and commemorated on another day, the 25th of December. This Roman feast quickly spread throughout Christendom and so we found ourselves with two celebrations of God’s revelation in Christ. Over time in the West, the feast of the Epiphany became an emphasis of the Adoration of the Magi over and above a celebration of the Baptism of the Lord. The East still retains the feast of the Epiphany, or Theophany as it is commonly called in the East, as primarily a celebration of the Baptism of the Lord. In 1955 the Roman Church, noting the change in emphasis of the feast of the Epiphany, again instituted a new feast for the Baptism of the Lord – originally on the 13th of January but quickly moved to the Sunday after Epiphany (unless you’re English!).

So we have three feasts in the West all celebrating separate aspects of the same event; a truly rich liturgical heritage and a whole season of the Church (Christmastide) with the Baptism of the Lord as the pivotal feast moving us from Christmas to Ordinary Time.

Jan Sadeler.

The Roots of Christmas

The assertion that Christmas is merely a “Christianized” pagan holiday simply isn't true.

In his book "The Origins of the Liturgical Year," Thomas Talley shows that Dec. 25 was celebrated in the early church by the third century and suggests a North African rather than Roman origin for the feast and its dating.

There were both theological and historical principles at work in arriving at that date. The process began by seeking to establish the likely historical date for the death of Jesus at Passover. This was thought to have been March 25. The annunciation was set to correspond with that date, so that, theologically, the conception of Jesus and the death of Jesus are observed as part of the same whole. The date to observe the birth of Jesus was then set by adding nine months to March 25, thus arriving at Dec. 25.

This process for historical and theological dating was already in place in some of the churches in North Africa as early as the late second century and appears to have spread across the churches from there. h/t J. Greer

Volume XVIII, Issue Ia

The Story of the Bethlehem Star

[click to read]

Someone once observed, “The universe is composed of stories, not atoms.” The Star of Bethlehem is certainly a story (as is most of the Bible, first and foremost). It is a mystery and a puzzle, involving not only theology and astronomy, but also history and even astrology. It is an attempt of men to understand not the universe at large, but specific events, or “What I Saw.” What do we know about the Star of Bethlehem? The popular conception is summarized in the Christmas carol: (read more)

Leaf by Niggle

A Short Work by J. R. R. Tolkien