Volume XIX, Issue Xa: Special Book Section

Apollonius

By Bob Kirchman

Copyright © 2020, The Kirchman Studio, all rights reserved

Chapter 7: Setting Course for Mars!

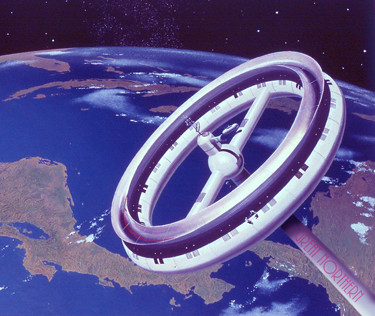

Unlike the Apollo Program, which had been built from the ground up through the Mercury and Gemini flights, The mission to Mars had been assembled in less than a year by using “off the shelf” technology. The Space station was simply attached to a long shaft that in turn was connected to the engine array. Of course, much testing was required to assure the flight worthiness of the combined systems but there were no ‘unknown’ systems being added. The closest thing to ‘unknown’ were the ten re-usable Mars landers. They had originally been created for a lunar mission but in anticipation of Mars flights, they had been ‘over engineered’ as far as power accordingly. The landers were not large. They carried a crew of five to seven people, anticipating that two people would be able to operate it for a return to the mother ship. Since each craft was capable of returning by free trajectory to Earth orbit, they were going to remain on the Martian surface as ‘lifeboats.’ There was also a missile to be delivered to the colony as a sort of ‘last resort’ signal (sort of like a distress flare). Since help was a year away, the flight directors wondered about this, but in the end it was decided that it should be kept.

Ben Gurion and his crew ran through the required test procedures for Great Northern and the landers. It was decided that he and Sarah would take the first lander down and so ‘fine tune’ the approach sequence. They would indeed set foot on the planet and deliver the first round of more delicate supplies. Less critical components would have already been parachuted down in one-way craft to a ‘drop zone’ outside the camp. This would allow the rapid deployment of a lot of construction supplies from the orbiting mother ship. On the mother ship was the master navigation computer, dubbed ‘Katherine’ in honor of NASA’s Katherine Goebbels Johnson, a very human ‘computer’ who in the 1960’s had calculated the paths of Apollo missions. One must remember that you can’t simply jump into a space ship and steer for the coordinates of your destination and then travel straight until you reach it. Everything in space is moving in elliptical orbits and to move from one place to another involves taking that into consideration. You must calculate an elliptical path between two objects moving in elliptical paths. You need to be aiming for the place your objective will be when you arrive.

That is why so many space dramas are simply unbelievable. You can’t pilot a spaceship looking out the window, so to speak. In the end it was decided that after the initial visit and return by Ben-Gurion and Cohen, the colonists would be ferried down in the landing craft under control from Great Northern and ‘Katherine.’ All ten would remain as escape vehicles should evacuation of the colony become necessary. They would fire the distress rocket, then begin the complete evacuation of the settlement. A medical emergency might be handled by the return of a single craft and it was probable that an Earth craft could depart with needed resources to join them in free return trajectory. The procedures and redundancy were all taken from work done in the preceding Century. Werner Von Braun had written a novel: Project Mars’ in 1952 which pretty much detailed the physics that would carry Ben-Gurion’s mission to the planet. Edgar Rice Burroughs had written A Princess on Mars and somewhat predicted the ‘atmosphere factory’ that would make it possible for men to live on Mars.

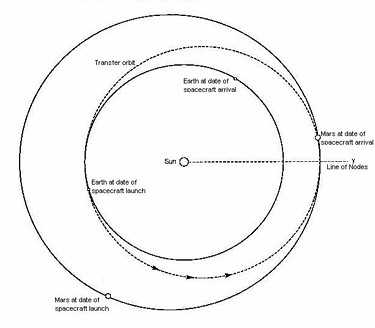

Contrary to the 'point and shoot' idea, an actual trip to mars looks very round a bout as the figure above shows for a typical 'minimum cost' trajectory. This, by the way, is called a Hoeman Transfer Orbit, and is the main stay of interplanetary space travel. It depends on the details of the orbit you take between the Earth and Mars. The typical time during Mars's closest approach to the Earth every 1.6 years is about 260 days. Again, the details depend on the rocket velocity and the closeness of the planets, but 260 days is the number I hear most often give or take 10 days. Some high-speed transfer orbits could make the trip in as little as 130 days. NASA Website

Though Arthur C. Clark and Kim Stanley Robinson predicted the terraforming of the entire planet, it was clear that only greenhouse/biosphere habitation could be made fit for humans to live in. The solar wind continually stripped the lean Martian CO2 atmosphere and scientists had pretty much disproved the global effect of manufacturing ‘greenhouse gasses.’ Planets, they had discovered, tend to balance themselves out in equations produced by a much larger equilibrium. Indeed, human pollution could create harmful inversions in Los Angeles and the Katmandu Valley, but the vastness of planet oceans and atmospheres tended to mitigate the effects on a global scale. George Apollonius had insisted that equipment be carried on the mission to test the theories that Mars could be terraformed, but at Cape Lisbon, scientists shook their heads knowing that even if it WAS possible it would require Centuries to accomplish.

The research they were anxious to see, on the other hand, was that of Dr. Stanley Kline, the flight surgeon. The observations of men and women in prolonged space environments was still very incomplete. Long-term exposure to cosmic radiation, lowered gravity and many aspects of life away from Earth were simply not well-enough known. Dr. Kline was the only unmarried member of the crew but he was a bit of a solitary melancholy fellow and seemed to thrive on his somewhat hermit-like existence. He had excelled in medical studies and had pioneered a lot of advances, but it had come at a cost. He had started medical school with a young wife and children but sacrificed them as he was driven by an unrelenting drive to be the best of the best. Finally the man who many thought was a machine started breaking down. He took the opportunity with the space program and moved out of his high-pressure world just in time to avoid the inevitable break-down. Somehow he felt the two-year voyage would take him back to the simplicity of his days working with white mice at Bowman Gray Medical Center. Astronauts tended to be a healthy lot, and the trip should provide little in the way of drama.

Dr. Kline looked forward to logging a rather mundane report, useful for future ventures into space, to be sure, but not at all Earth-shattering. He looked forward to Skype time with his sons, who would likely take some pride in their father’s accomplishment. Still, two years of their young lives would pass without human touch. Sometimes he thought about that and felt a twinge of remorse. The remainder of the crew were two more couples who were also pilots, but who had unique scientific or engineering backgrounds, deepening the crew. Finally there were the stewards, chief cook Maria Giuliano and her husband Salvador. Final supplying of the ship took place and with very little fanfare, the Great Northern’s engines began pushing her out of Earth orbit toward her rendezvous with Mars. The actual departure was governed by the orbits of the planets and was timed to allow for the shortest possible trip. Still, it was about nine month's journey nonetheless. Economy was important due to the sheer magnitude of the journey and Zimmerman’s setting of a pretty austere budget.

Cape Lisbon Command kept constant communication with the crew. Flight director Joseph West had worked with Ben-Gurion and his wife long enough that they could pick up much information beyond their spoken words in voice inflection and hesitation or pauses. “Cleared for Mars transit insertion,” West blandly stated. “Hold course 1129 as directed by ‘Katherine.’ Dorothy/Mary confirm. Inform command of all corrective burns/maneuvers en route.”

The computer was essentially flying the ship. Human monitoring was a redundancy but in an unknown environment it was a most necessary redundancy.

Ground computers received ‘Katherine’s’ calculated trajectory numbers and continually verified them. Should the computer on Great Northern fail, there was a backup named ‘Dorothy.’ On the ground they were backed up by ‘Mary.’ Since it was impossible to fly the ship without continual input from the computers, this was essential redundancy. The three computers would be in constant communication except for those minutes where the spacecraft was orbiting the far side of Mars. Then ‘Mary’ would have to catch the position and trajectory of the starship and account for any discrepancy.

(to be continued)

[click to read ]

Copyright © 2020, The Kirchman Studio, all rights reserved