Volume XX, Issue XI: Leonardo da Vinci City Planning

Leonardo da Vinci’s Pandemic Inspired Planning

And How it Might Help Us Today

By Bob Kirchman

In the years 1484 and 1485 the bubonic plague ravaged Milan. Though this was during the Renaissance, the city itself was Medieval in its plan with narrow streets crowded with a hodgepodge of shops, houses and other essential buildings. Sanitation was terrible and sunlight often never penetrated the narrow streets. The great Renaissance polymath saw this as a breeding ground for pestilence, and so he set to work to create a better city. In his notebooks he drew an open plan with wide spaces and canals – open to sunlight and with separation between passageways for freight and refuse and those for pedestrians. It was a first step towards modern city planning. 1.

The buildings were classical in form and multistory. Shops and services were on the lower levels and residences on the floors above. Fresh air and sunlight would freely waft in upon the houses above. The nasty dirty necessities of city life would be relegated to underground tunnels. This was a forward looking approach for sure. Unfortunately Ludovico Sforza, the Duke and absolute ruler of Milan, had little interest in rebuilding the fabric of his city so the idea remained on paper. Il Moro had more pressing matters on his mind as the French king sought at that time to conquer the powerful duchy. Eventually Renaissance planning would open up plazas and grand avenues, but this would be more driven by the need to create grand processional avenues to showcase important architecture and monuments.

The villages of great and peaceful republics would also place spaces between houses and allow for gardens as well as light and fresh air. Consider Colonial Williamsburg, where the gardens and grounds of the historic buildings are much cherished even in our day. Cities that no longer needed to crowd behind walls for defense naturally spaced themselves in a more appealing manner. On the frontier there were still fortifications around settlements but the lands that were settled far away from hostile enemies grew up open to the surrounding farms, fields and woodlands. Even our Revolution and our vicious Civil War were events so out of the ordinary that American cities did not hunker into walled fortifications. The Capital of our republic was actually laid out like the great hunting garden at the Palace of Versailles. There were even to be canals in the area now occupied by the National Mall. Pierre L’Enfant overlayed a grid with diagonal avenues in 1791 that was also crossed by canals, not unlike the drawings of Leonardo.

The machine age would fill the open avenues with railway tracks and then automobiles. By the end of the Nineteenth Century the major cities were reaching skyward. Again, density became the rule. Large cities like New York and Chicago again found themselves shut in from light and fresh air. Though advances in the design of waterworks and sewers helped, it was not uncommon for the wealthy to leave the cities in the Summertme for country homes and their benefits. Air conditioning made it possible for people to function more comfortably in the urban Summers and vacations became a more universal and more short-term practice for all classes of Americans. Streetcar suburbs allowed for year-round life in less crowded circumstances.

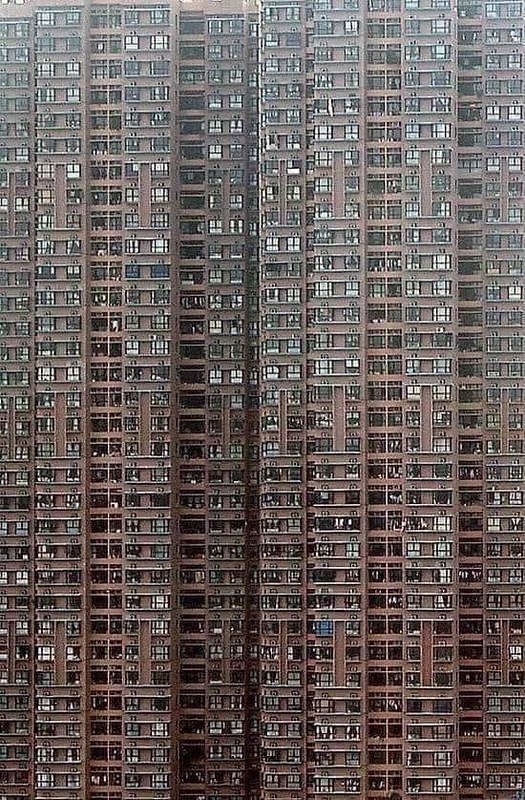

The coming of the automobile age was indeed a mixed blessing as more roads and parking spaces crowded into spaces needed for living. Buildings grew taller in the center of town while the suburbs kept moving outward. Eventually you had a new level of crowding, crowded highways, crowded elevators, and crowded transit. The last century saw the rise of the great Asian megacities. Though they seem to have been built largely for show, they crowd people into ‘Vertical Medievalism,’ small apartments packed close together in buildings that rise many stories. It was here that the modern pandemic would rage out of control. A virus born in Wuhan would rage through entire apartment buildings as frightened officials sealed the doors. Many died as a result. The shared utilities of such buildings served as a conduit for pestilence.

“Vertical Medievalism:” A multistory apartment building in Hong Kong.

Centralization has many benefits for economies of scale and in times past, defense. But urban planner Charles Marahone recently referenced some drawings by New Urbanist Leon Krier which show an interesting alternative – one that we might actually emulate. 2. Krier shows us the pattern of our cities at present, growing ever dense and upward at their cores and sprawling outward. This, says Marahone, is a recipe for pandemic. What if, muses Marahone, we instead let smaller towns grow spaced out from the mother city. With the increasing trend of remote working it becomes less necessary for large companies to concentrate their workers in high-rise buildings or suburban mega-campuses. Remote workers love the closeness to family and smaller community but miss the places where people come together, the centers of culture. To that end, Krier’s smaller town centers, spaced apart, make a lot of sense. Most people would live and work in a more convivial setting that was also less in contact with the great wide world. People would still enjoy the ability to move about, but would no longer crowd together twice a day on transportation.

Services would now be, of necessity, a thing to be provided locally. More people would be employed closer to home, doing what they do, that cannot be done remotely. Separation, a concept first visited by da Vinci, would now be possible on a regional scale. But, remembering that El Moro wasn’t ready to rebuild Milan, how do we in the 21st Century find the resolve to rebuild American Villages. The answer may be simpler than we think. For years a little village has languished near my home – the little town of Stuarts Draft. The old town center is lifeless, but the factories that drive the economy of Augusta County and a lot of suburban housing surround it. Here is an opportunity to reestablish a center, as Leon Krier envisions, of community activity. Many of our dead strip malls can be rezoned as multipurpose developments with housing and locally essential retail and services replacing the shuttered rows of storefronts.

Think of a world where people live in smaller community, open to the beauty of forest and farmland, but buffered from the great waves of pandemic and stresses of commuting. This is a world where people might live closer to their children, taking a lunch-time for a school event with them or just meeting with them for an hour in the park. It is a way to create more interaction, not less, while creating a healthy level of built-in ‘social distancing’ at the same time.

1 Paris Manuscript B, Leonardo da Vinci

2 Do You Want to Know What Works? Charles Marahone in Strong Towns, May 28, 2019

PDF Version [click to read]

A section of a building from Paris Manuscript B, Leonardo da Vinci

Architecture Biennale 2016 exhibit: Leonardo da Vinci – Water City

Architecture Biennale 2016 exhibit: Leonardo da Vinci – Water City

Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci envisioned residences above shops and services, canals and separated walkways...

Here I have developed Leonardo da Vinci's exercise in city planning as a mixed use project to be built on the site of a dying mall. I added some trees and greenery to the final vision.

...which might be employed in the design of a village center replacing a dying mall.

Here the pool is replaced by greenspace in another variation.