Volume XV, Issue II

F. P. Schubert - Ave María

Celebrating the Sacred: Fantasia, 1940, Walt Disney

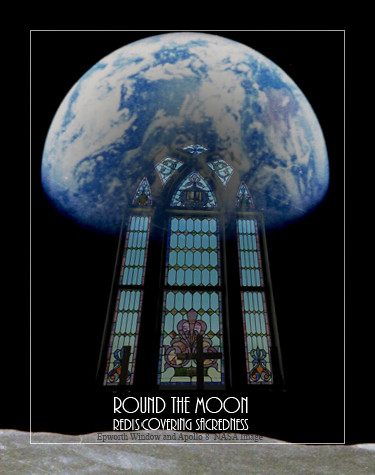

Rediscovering Sacredness

A young author visited me in the studio recently and spoke of a passion to restore a sense of the sacred to the literary vocabulary, particularly where our modern society is obsessed with providing ‘information.’ We now have at our fingertips resources our parents could not have dreamed of for ‘knowing things.’ Have we in our rush to be informed cast away the wonder? I would love to see our present technologies pursued much as the Fantasia artists pursued film and the use of the multiplane camera in the 1930s. Much as C. S. Lewis rediscovered Wonder in his rationalist age, we too need to reconnect with the Magical and Miraculous observation of life!

Counterpoint to Coruscant

Two Arguments Set in Stone for a Low Profile Capital

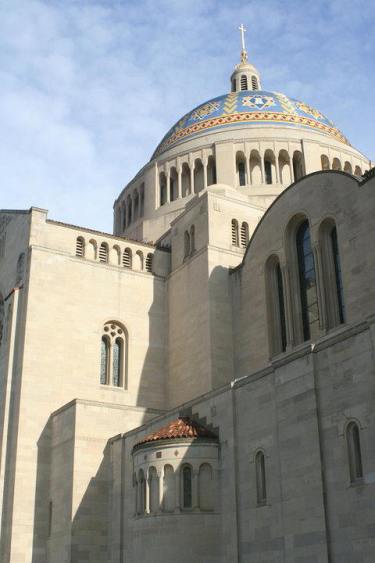

The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception... Photo by Kristina Elaine Greer.

...is a fine example of Byzantine-Romanesque architecture. Photo by Kristina Elaine Greer.

The Shrine and the Cathedral

One unique distinctive of the city of Washington is its relatively low profile. The capital of the greatest nation on the face of the Earth is a city without skyscrapers. New York and Chicago, the great engines of finance and commerce, thrust their architectural presence into the sky while the nation's capital's relatively modest scale defers to iconic buildings that speak of the history and aspirations of her people.

It is widely believed that the legislation controlling building heights was put in place to make sure the Washington Monument would remain the tallest building in the city. The actual legislation has to do with the height of buildings in relation to the width of the streets they occupy.

The Height of Buildings Act of 1910 restricts all buildings in Washington D.C. to being no higher than the width of the adjacent street plus 20 feet. A building on a street that is 130 feet wide can only be 150 feet tall. To be taller than the 555 foot Washington Monument without violating this law, a building would need to be on a street that is over 535 feet wide.

The result is a city who's outlying neighborhoods open to vistas of splendid shrines and cathedrals. Her Northern neighborhoods are crowned by two architectural treasures: the National Cathedral and the the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception.

Pierre Charles L'Enfant's original vision for the city, based on the palace and garden of Versailles, lends itself well to a garden city punctuated by such fine monuments. The gothic National cathedral brings to mind the great churches of Europe.

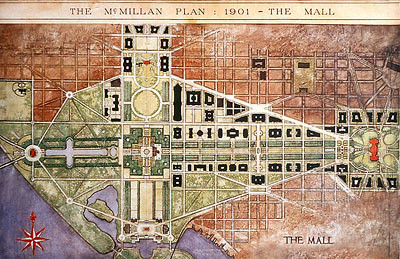

The McMillan Plan.

Pierre Charles L'Enfant's "Plan of the Federal City,” drawn in 1792,set aside a prominent site for a "great church for national purposes." Today the National Portrait Gallery stands in that place. It was not until 1891 that a meeting was held to renew plans for a National Cathedral. L’Enfant’s grand plan gave way to the Nineteenth Century growth of the city. Train tracks ran across what would become the National Mall.

At the beginning of the Twentieth Century, The United States Senate Park Commission was formed. Known as the McMillan Commission, it was named for its chairman, Senator James McMillan of Michigan. Some of the greatest American architects, landscape architects, and urban planners of the day served on the McMillan Commission, including Daniel Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., Charles F. McKim, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Washington DC that we know today, with it’s inspiring vistas, cherry trees and reflecting pools is largely the product of this commission.

In 1902 the commission’s plan was published. Building on the work of L’Enfant, and inspired by the Cities Beautiful Movement, a grand but beautifully scaled Washington began to take shape. In her Northern reaches, plans for two beautiful houses of worship were also taking shape.

Frederick Bodley, known for his fine church designs in England, led the team designing the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul for the Episcopal Diocese of Washington. [1.] Construction began in 1907. After World War I, Philip Hubert Frohman, an American architect, took over the supervision of the work. Construction of the National Cathedral went on for most of the Twentieth Century. As good stonemasons became harder to find, work was speeded up. Then a program to train stone masons was established on the Cathedral grounds. The Gothic cathedral features beautiful bas relief sculptures of the Creation and a gargoyle that resembles French President Charles DeGaulle! A statue of Darth Vader [2.] is up there as well, sculpted by Jay Hall Carpenter and Patrick J. Plunkett. The building was completed in 1990.

Today the cathedral is a prominent feature of the Northwest Quadrant of the city.

Bishop Thomas Joseph Shahan, the fourth rector of the Catholic University of America envisioned the construction of a national shrine to commemorate the Immaculate Conception in the country's capital. [3.] He took his appeal to Pope Pius X on August 15, 1913. The Pope was excited by Shahan’s vision and Catholic University donated land on its campus in the Northeast Quadrant of the city.

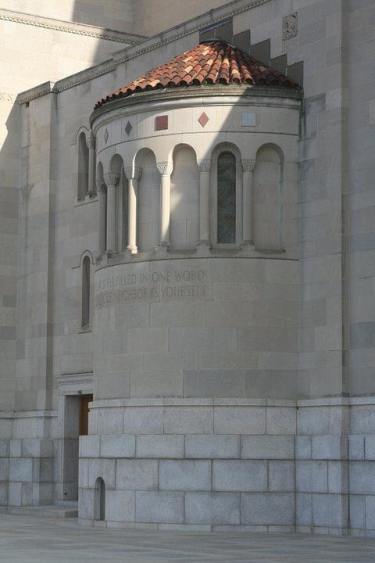

Architects Maginnis and Walsh of Boston first proposed a gothic building as well, but Bishop Shahan wanted the shrine to be bold, glorious and unique. A Byzantine-Romanesque design was chosen. The archbishop of Baltimore, Cardinal James Gibbons, blessed the foundation stone on September 23, 1920.

The Great Depression halted construction, as did the Second World War. In 1953 construction resumed and continued through the Twentieth Century. There are still mosaics remaining to be completed in the great dome, but the building is essentially complete. The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception rises above the grey buildings of Catholic University as a prominent feature of the cityscape.

Thus two great architectural testimonies of faith hold their place in the profile of our nation’s capital. Neither is supported by federal monies but the presence of both stands as a reminder that: “Behold, the nations are as a drop of a bucket, and are counted as the small dust of the balance: behold, he taketh up the isles as a very little thing.” -- Isaiah 40:15

Tower... Photo by Kristina Elaine Greer.

...and tile of the National Shrine. Photo by Kristina Elaine Greer.

The National Cathedral. Photo by Kristina Elaine Greer.

Rose window in the cathedral. Photo by Kristina Elaine Greer.

Flying buttresses of the cathedral. Photo by Kristina Elaine Greer.

PSALM 48

Great is the Lord, and greatly to be praised in the city of our God, in the mountain of his holiness. Beautiful for situation, the joy of the whole earth, is mount Zion, on the sides of the north, the city of the great King. God is known in her palaces for a refuge. For, lo, the kings were assembled, they passed by together. They saw it, and so they marvelled; they were troubled, and hasted away. Fear took hold upon them there, and pain, as of a woman in travail. Thou breakest the ships of Tarshish with an east wind. As we have heard, so have we seen in the city of the Lord of hosts, in the city of our God: God will establish it for ever. Selah. We have thought of thy lovingkindness, O God, in the midst of thy temple. According to thy name, O God, so is thy praise unto the ends of the earth: thy right hand is full of righteousness. Let mount Zion rejoice, let the daughters of Judah be glad, because of thy judgments. Walk about Zion, and go round about her: tell the towers thereof. Mark ye well her bulwarks, consider her palaces; that ye may tell it to the generation following. For this God is our God for ever and ever: he will be our guide even unto death.” — Psalm 48

Epworth United Methodist Church Beneath the Mountain.

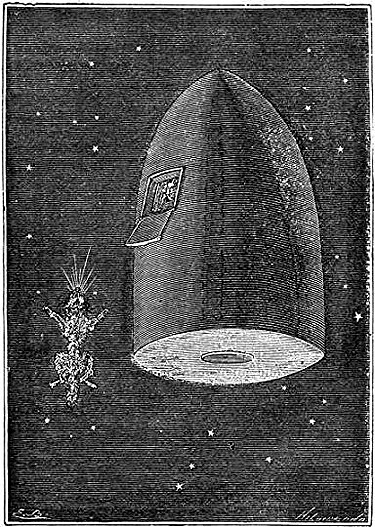

Round the Moon

By Jules Verne

CHAPTER III, THEIR PLACE OF SHELTER

This curious but certainly correct explanation once given, the three friends returned to their slumbers. Could they have found a calmer or more peaceful spot to sleep in? On the earth, houses, towns, cottages, and country feel every shock given to the exterior of the globe. On sea, the vessels rocked by the waves are still in motion; in the air, the balloon oscillates incessantly on the fluid strata of divers densities. This projectile alone, floating in perfect space, in the midst of perfect silence, offered perfect repose.

Thus the sleep of our adventurous travelers might have been indefinitely prolonged, if an unexpected noise had not awakened them at about seven o'clock in the morning of the 2nd of December, eight hours after their departure.

This noise was a very natural barking.

The dogs! it is the dogs!" exclaimed Michel Ardan, rising at once.

They are hungry," said Nicholl.

By Jove!" replied Michel, "we have forgotten them."

Where are they?" asked Barbicane.

They looked and found one of the animals crouched under the divan. Terrified and shaken by the initiatory shock, it had remained in the corner till its voice returned with the pangs of hunger. It was the amiable Diana, still very confused, who crept out of her retreat, though not without much persuasion, Michel Ardan encouraging her with most gracious words.

Come, Diana," said he: "come, my girl! thou whose destiny will be marked in the cynegetic annals; thou whom the pagans would have given as companion to the god Anubis, and Christians as friend to St. Roch; thou who art rushing into interplanetary space, and wilt perhaps be the Eve of all Selenite dogs! come, Diana, come here."

Diana, flattered or not, advanced by degrees, uttering plaintive cries.

Good," said Barbicane: "I see Eve, but where is Adam?"

Adam?" replied Michel; "Adam cannot be far off; he is there somewhere; we must call him. Satellite! here, Satellite!"

But Satellite did not appear. Diana would not leave off howling. They found, however, that she was not bruised, and they gave her a pie, which silenced her complaints. As to Satellite, he seemed quite lost. They had to hunt a long time before finding him in one of the upper compartments of the projectile, whither some unaccountable shock must have violently hurled him. The poor beast, much hurt, was in a piteous state.

The devil!" said Michel.

They brought the unfortunate dog down with great care. Its skull had been broken against the roof, and it seemed unlikely that he could recover from such a shock. Meanwhile, he was stretched comfortably on a cushion. Once there, he heaved a sigh.

We will take care of you," said Michel; "we are responsible for your existence. I would rather lose an arm than a paw of my poor Satellite."

Saying which, he offered some water to the wounded dog, who swallowed it with avidity.

This attention paid, the travelers watched the earth and the moon attentively. The earth was now only discernible by a cloudy disc ending in a crescent, rather more contracted than that of the previous evening; but its expanse was still enormous, compared with that of the moon, which was approaching nearer and nearer to a perfect circle.

By Jove!" said Michel Ardan, "I am really sorry that we did not start when the earth was full, that is to say, when our globe was in opposition to the sun."

Why?" said Nicholl.

Because we should have seen our continents and seas in a new light-- the first resplendent under the solar rays, the latter cloudy as represented on some maps of the world. I should like to have seen those poles of the earth on which the eye of man has never yet rested."

I dare say," replied Barbicane; "but if the earth had been full, the moon would have been new; that is to say, invisible, because of the rays of the sun. It is better for us to see the destination we wish to reach, than the point of departure."

You are right, Barbicane," replied Captain Nicholl; "and, besides, when we have reached the moon, we shall have time during the long lunar nights to consider at our leisure the globe on which our likenesses swarm."

Our likenesses!" exclaimed Michel Ardan; "They are no more our likenesses than the Selenites are! We inhabit a new world, peopled by ourselves-- the projectile! I am Barbicane's likeness, and Barbicane is Nicholl's. Beyond us, around us, human nature is at an end, and we are the only population of this microcosm until we become pure Selenites."

In about eighty-eight hours," replied the captain.

Which means to say?" asked Michel Ardan.

That it is half-past eight," replied Nicholl.

Very well," retorted Michel; "then it is impossible for me to find even the shadow of a reason why we should not go to breakfast."

Indeed the inhabitants of the new star could not live without eating, and their stomachs were suffering from the imperious laws of hunger. Michel Ardan, as a Frenchman, was declared chief cook, an important function, which raised no rival. The gas gave sufficient heat for the culinary apparatus, and the provision box furnished the elements of this first feast.

The breakfast began with three bowls of excellent soup, thanks to the liquefaction in hot water of those precious cakes of Liebig, prepared from the best parts of the ruminants of the Pampas. To the soup succeeded some beefsteaks, compressed by an hydraulic press, as tender and succulent as if brought straight from the kitchen of an English eating-house. Michel, who was imaginative, maintained that they were even "red."

Preserved vegetables ("fresher than nature," said the amiable Michel) succeeded the dish of meat; and was followed by some cups of tea with bread and butter, after the American fashion.

The beverage was declared exquisite, and was due to the infusion of the choicest leaves, of which the emperor of Russia had given some chests for the benefit of the travelers.

And lastly, to crown the repast, Ardan had brought out a fine bottle of Nuits, which was found "by chance" in the provision-box. The three friends drank to the union of the earth and her satellite.

And, as if he had not already done enough for the generous wine which he had distilled on the slopes of Burgundy, the sun chose to be part of the party. At this moment the projectile emerged from the conical shadow cast by the terrestrial globe, and the rays of the radiant orb struck the lower disc of the projectile direct occasioned by the angle which the moon's orbit makes with that of the earth.

The sun!" exclaimed Michel Ardan.

No doubt," replied Barbicane; "I expected it."

But," said Michel, "the conical shadow which the earth leaves in space extends beyond the moon?"

Far beyond it, if the atmospheric refraction is not taken into consideration," said Barbicane. "But when the moon is enveloped in this shadow, it is because the centers of the three stars, the sun, the earth, and the moon, are all in one and the same straight line. Then the nodes coincide with the phases of the moon, and there is an eclipse. If we had started when there was an eclipse of the moon, all our passage would have been in the shadow, which would have been a pity."

Why?"

Because, though we are floating in space, our projectile, bathed in the solar rays, will receive light and heat. It economizes the gas, which is in every respect a good economy."

Indeed, under these rays which no atmosphere can temper, either in temperature or brilliancy, the projectile grew warm and bright, as if it had passed suddenly from winter to summer. The moon above, the sun beneath, were inundating it with their fire.

It is pleasant here," said Nicholl.

I should think so," said Michel Ardan. "With a little earth spread on our aluminum planet we should have green peas in twenty-four hours. I have but one fear, which is that the walls of the projectile might melt."

Calm yourself, my worthy friend," replied Barbicane; "the projectile withstood a very much higher temperature than this as it slid through the strata of the atmosphere. I should not be surprised if it did not look like a meteor on fire to the eyes of the spectators in Florida."

But then J. T. Maston will think we are roasted!"

What astonishes me," said Barbicane, "is that we have not been. That was a danger we had not provided for."

I feared it," said Nicholl simply.

And you never mentioned it, my sublime captain," exclaimed Michel Ardan, clasping his friend's hand.

Barbicane now began to settle himself in the projectile as if he was never to leave it. One must remember that this aerial car had a base with a superficies of fifty-four square feet. Its height to the roof was twelve feet. Carefully laid out in the inside, and little encumbered by instruments and traveling utensils, which each had their particular place, it left the three travelers a certain freedom of movement. The thick window inserted in the bottom could bear any amount of weight, and Barbicane and his companions walked upon it as if it were solid plank; but the sun striking it directly with its rays lit the interior of the projectile from beneath, thus producing singular effects of light.

They began by investigating the state of their store of water and provisions, neither of which had suffered, thanks to the care taken to deaden the shock. Their provisions were abundant, and plentiful enough to last the three travelers for more than a year. Barbicane wished to be cautious, in case the projectile should land on a part of the moon which was utterly barren. As to water and the reserve of brandy, which consisted of fifty gallons, there was only enough for two months; but according to the last observations of astronomers, the moon had a low, dense, and thick atmosphere, at least in the deep valleys, and there springs and streams could not fail. Thus, during their passage, and for the first year of their settlement on the lunar continent, these adventurous explorers would suffer neither hunger nor thirst.

Now about the air in the projectile. There, too, they were secure. Reiset and Regnaut's apparatus, intended for the production of oxygen, was supplied with chlorate of potassium for two months. They necessarily consumed a certain quantity of gas, for they were obliged to keep the producing substance at a temperature of above 400@. But there again they were all safe. The apparatus only wanted a little care. But it was not enough to renew the oxygen; they must absorb the carbonic acid produced by expiration. During the last twelve hours the atmosphere of the projectile had become charged with this deleterious gas. Nicholl discovered the state of the air by observing Diana panting painfully. The carbonic acid, by a phenomenon similar to that produced in the famous Grotto del Cane, had collected at the bottom of the projectile owing to its weight. Poor Diana, with her head low, would suffer before her masters from the presence of this gas. But Captain Nicholl hastened to remedy this state of things, by placing on the floor several receivers containing caustic potash, which he shook about for a time, and this substance, greedy of carbonic acid, soon completely absorbed it, thus purifying the air.

An inventory of instruments was then begun. The thermometers and barometers had resisted, all but one minimum thermometer, the glass of which was broken. An excellent aneroid was drawn from the wadded box which contained it and hung on the wall. Of course it was only affected by and marked the pressure of the air inside the projectile, but it also showed the quantity of moisture which it contained. At that moment its needle oscillated between 25.24 and 25.08.

It was fine weather.

Barbicane had also brought several compasses, which he found intact. One must understand that under present conditions their needles were acting wildly, that is without any constant direction. Indeed, at the distance they were from the earth, the magnetic pole could have no perceptible action upon the apparatus; but the box placed on the lunar disc might perhaps exhibit some strange phenomena. In any case it would be interesting to see whether the earth's satellite submitted like herself to its magnetic influence.

A hypsometer to measure the height of the lunar mountains, a sextant to take the height of the sun, glasses which would be useful as they neared the moon, all these instruments were carefully looked over, and pronounced good in spite of the violent shock.

As to the pickaxes and different tools which were Nicholl's especial choice; as to the sacks of different kinds of grain and shrubs which Michel Ardan hoped to transplant into Selenite ground, they were stowed away in the upper part of the projectile. There was a sort of granary there, loaded with things which the extravagant Frenchman had heaped up. What they were no one knew, and the good-tempered fellow did not explain. Now and then he climbed up by cramp-irons riveted to the walls, but kept the inspection to himself. He arranged and rearranged, he plunged his hand rapidly into certain mysterious boxes, singing in one of the falsest of voices an old French refrain to enliven the situation.

Barbicane observed with some interest that his guns and other arms had not been damaged. These were important, because, heavily loaded, they were to help lessen the fall of the projectile, when drawn by the lunar attraction (after having passed the point of neutral attraction) on to the moon's surface; a fall which ought to be six times less rapid than it would have been on the earth's surface, thanks to the difference of bulk. The inspection ended with general satisfaction, when each returned to watch space through the side windows and the lower glass coverlid.

There was the same view. The whole extent of the celestial sphere swarmed with stars and constellations of wonderful purity, enough to drive an astronomer out of his mind! On one side the sun, like the mouth of a lighted oven, a dazzling disc without a halo, standing out on the dark background of the sky! On the other, the moon returning its fire by reflection, and apparently motionless in the midst of the starry world. Then, a large spot seemingly nailed to the firmament, bordered by a silvery cord; it was the earth! Here and there nebulous masses like large flakes of starry snow; and from the zenith to the nadir, an immense ring formed by an impalpable dust of stars, the "Milky Way," in the midst of which the sun ranks only as a star of the fourth magnitude. The observers could not take their eyes from this novel spectacle, of which no description could give an adequate idea. What reflections it suggested! What emotions hitherto unknown awoke in their souls! Barbicane wished to begin the relation of his journey while under its first impressions, and hour after hour took notes of all facts happening in the beginning of the enterprise. He wrote quietly, with his large square writing, in a business-like style.

During this time Nicholl, the calculator, looked over the minutes of their passage, and worked out figures with unparalleled dexterity. Michel Ardan chatted first with Barbicane, who did not answer him, and then with Nicholl, who did not hear him, with Diana, who understood none of his theories, and lastly with himself, questioning and answering, going and coming, busy with a thousand details; at one time bent over the lower glass, at another roosting in the heights of the projectile, and always singing. In this microcosm he represented French loquacity and excitability, and we beg you to believe that they were well represented. The day, or rather (for the expression is not correct) the lapse of twelve hours, which forms a day upon the earth, closed with a plentiful supper carefully prepared.

No accident of any nature had yet happened to shake the travelers' confidence; so, full of hope, already sure of success, they slept peacefully, while the projectile under an uniformly decreasing speed was crossing the sky.

CHAPTER IV, A LITTLE ALGEBRA

The night passed without incident. The word "night," however, is scarcely applicable.

The position of the projectile with regard to the sun did not change. Astronomically, it was daylight on the lower part, and night on the upper; so when during this narrative these words are used, they represent the lapse of time between rising and setting of the sun upon the earth.

The travelers' sleep was rendered more peaceful by the projectile's excessive speed, for it seemed absolutely motionless. Not a motion betrayed its onward course through space. The rate of progress, however rapid it might be, cannot produce any sensible effect on the human frame when it takes place in a vacuum, or when the mass of air circulates with the body which is carried with it. What inhabitant of the earth perceives its speed, which, however, is at the rate of 68,000 miles per hour? Motion under such conditions is "felt" no more than repose; and when a body is in repose it will remain so as long as no strange force displaces it; if moving, it will not stop unless an obstacle comes in its way. This indifference to motion or repose is called inertia.

Barbicane and his companions might have believed themselves perfectly stationary, being shut up in the projectile; indeed, the effect would have been the same if they had been on the outside of it. Had it not been for the moon, which was increasing above them, they might have sworn that they were floating in complete stagnation.

That morning, the 3rd of December, the travelers were awakened by a joyous but unexpected noise; it was the crowing of a cock which sounded through the car. Michel Ardan, who was the first on his feet, climbed to the top of the projectile, and shutting a box, the lid of which was partly open, said in a low voice, "Will you hold your tongue? That creature will spoil my design!"

But Nicholl and Barbicane were awake.

A cock!" said Nicholl.

Why no, my friends," Michel answered quickly; "it was I who wished to awake you by this rural sound." So saying, he gave vent to a splendid cock-a-doodledoo, which would have done honor to the proudest of poultry-yards.

The two Americans could not help laughing.

Fine talent that," said Nicholl, looking suspiciously at his companion.

Yes," said Michel; "a joke in my country. It is very Gallic; they play the cock so in the best society."

Then turning the conversation:

Barbicane, do you know what I have been thinking of all night?" "No," answered the president.

Of our Cambridge friends. You have already remarked that I am an ignoramus in mathematical subjects; and it is impossible for me to find out how the savants of the observatory were able to calculate what initiatory speed the projectile ought to have on leaving the Columbiad in order to attain the moon."

You mean to say," replied Barbicane, "to attain that neutral point where the terrestrial and lunar attractions are equal; for, starting from that point, situated about nine-tenths of the distance traveled over, the projectile would simply fall upon the moon, on account of its weight."

So be it," said Michel; "but, once more; how could they calculate the initiatory speed?"

Nothing can be easier," replied Barbicane.

And you knew how to make that calculation?" asked Michel Ardan.

Perfectly. Nicholl and I would have made it, if the observatory had not saved us the trouble."

Very well, old Barbicane," replied Michel; "they might have cut off my head, beginning at my feet, before they could have made me solve that problem."

Because you do not know algebra," answered Barbicane quietly.

Ah, there you are, you eaters of x^1; you think you have said all when you have said `Algebra.'"

Michel," said Barbicane, "can you use a forge without a hammer, or a plow without a plowshare?"

Hardly."

Well, algebra is a tool, like the plow or the hammer, and a good tool to those who know how to use it."

Seriously?"

Quite seriously."

And can you use that tool in my presence?"

If it will interest you."

And show me how they calculated the initiatory speed of our car?"

Yes, my worthy friend; taking into consideration all the elements of the problem, the distance from the center of the earth to the center of the moon, of the radius of the earth, of its bulk, and of the bulk of the moon, I can tell exactly what ought to be the initiatory speed of the projectile, and that by a simple formula."

Let us see."

You shall see it; only I shall not give you the real course drawn by the projectile between the moon and the earth in considering their motion round the sun.

No, I shall consider these two orbs as perfectly motionless, which will answer all our purpose."

And why?"

Because it will be trying to solve the problem called `the problem of the three bodies,' for which the integral calculus is not yet far enough advanced."

Then," said Michel Ardan, in his sly tone, "mathematics have not said their last word?"

Certainly not," replied Barbicane.

Well, perhaps the Selenites have carried the integral calculus farther than you have; and, by the bye, what is this `integral calculus?'"

It is a calculation the converse of the differential," replied Barbicane seriously.

Much obliged; it is all very clear, no doubt."

And now," continued Barbicane, "a slip of paper and a bit of pencil, and before a half-hour is over I will have found the required formula."

Half an hour had not elapsed before Barbicane, raising his head, showed Michel Ardan a page covered with algebraical signs, in which the general formula for the solution was contained.

Well, and does Nicholl understand what that means?"

Of course, Michel," replied the captain. "All these signs, which seem cabalistic to you, form the plainest, the clearest, and the most logical language to those who know how to read it."

And you pretend, Nicholl," asked Michel, "that by means of these hieroglyphics, more incomprehensible than the Egyptian Ibis, you can find what initiatory speed it was necessary to give the projectile?"

Incontestably," replied Nicholl; "and even by this same formula I can always tell you its speed at any point of its transit."

On your word?"

On my word."

Then you are as cunning as our president."

No, Michel; the difficult part is what Barbicane has done; that is, to get an equation which shall satisfy all the conditions of the problem. The remainder is only a question of arithmetic, requiring merely the knowledge of the four rules."

That is something!" replied Michel Ardan, who for his life could not do addition right, and who defined the rule as a Chinese puzzle, which allowed one to obtain all sorts of totals.

The expression v zero, which you see in that equation, is the speed which the projectile will have on leaving the atmosphere."

Just so," said Nicholl; "it is from that point that we must calculate the velocity, since we know already that the velocity at departure was exactly one and a half times more than on leaving the atmosphere."

I understand no more," said Michel.

It is a very simple calculation," said Barbicane.

Not as simple as I am," retorted Michel.

That means, that when our projectile reached the limits of the terrestrial atmosphere it had already lost one-third of its initiatory speed."

As much as that?"

Yes, my friend; merely by friction against the atmospheric strata. You understand that the faster it goes the more resistance it meets with from the air."

That I admit," answered Michel; "and I understand it, although your x's and zero's, and algebraic formula, are rattling in my head like nails in a bag."

First effects of algebra," replied Barbicane; "and now, to finish, we are going to prove the given number of these different expressions, that is, work out their value."

Finish me!" replied Michel.

Barbicane took the paper, and began to make his calculations with great rapidity. Nicholl looked over and greedily read the work as it proceeded.

That's it! that's it!" at last he cried.

Is it clear?" asked Barbicane.

It is written in letters of fire," said Nicholl.

Wonderful fellows!" muttered Ardan.

Do you understand it at last?" asked Barbicane.

Do I understand it?" cried Ardan; "my head is splitting with it."

And now," said Nicholl, "to find out the speed of the projectile when it leaves the atmosphere, we have only to calculate that."

The captain, as a practical man equal to all difficulties, began to write with frightful rapidity. Divisions and multiplications grew under his fingers; the figures were like hail on the white page. Barbicane watched him, while Michel Ardan nursed a growing headache with both hands.

Very well?" asked Barbicane, after some minutes' silence.

Well!" replied Nicholl; "every calculation made, v zero, that is to say, the speed necessary for the projectile on leaving the atmosphere, to enable it to reach the equal point of attraction, ought to be----"

Yes?" said Barbicane.

Twelve thousand yards."

What!" exclaimed Barbicane, starting; "you say----"

Twelve thousand yards."

The devil!" cried the president, making a gesture of despair.

What is the matter?" asked Michel Ardan, much surprised.

What is the matter! why, if at this moment our speed had already diminished one-third by friction, the initiatory speed ought to have been----"

Seventeen thousand yards."

And the Cambridge Observatory declared that twelve thousand yards was enough at starting; and our projectile, which only started with that speed----"

Well?" asked Nicholl.

Well, it will not be enough."

Good."

We shall not be able to reach the neutral point."

The deuce!"

We shall not even get halfway."

In the name of the projectile!" exclaimed Michel Ardan, jumping as if it was already on the point of striking the terrestrial globe.

And we shall fall back upon the earth!"

CHAPTER V, THE COLD OF SPACE

This revelation came like a thunderbolt. Who could have expected such an error in calculation? Barbicane would not believe it. Nicholl revised his figures: they were exact. As to the formula which had determined them, they could not suspect its truth; it was evident that an initiatory velocity of seventeen thousand yards in the first second was necessary to enable them to reach the neutral point.

The three friends looked at each other silently. There was no thought of breakfast. Barbicane, with clenched teeth, knitted brows, and hands clasped convulsively, was watching through the window. Nicholl had crossed his arms, and was examining his calculations. Michel Ardan was muttering:

That is just like these scientific men: they never do anything else. I would give twenty pistoles if we could fall upon the Cambridge Observatory and crush it, together with the whole lot of dabblers in figures which it contains."

Suddenly a thought struck the captain, which he at once communicated to Barbicane.

Ah!" said he; "it is seven o'clock in the morning; we have already been gone thirty-two hours; more than half our passage is over, and we are not falling that I am aware of."

Barbicane did not answer, but after a rapid glance at the captain, took a pair of compasses wherewith to measure the angular distance of the terrestrial globe; then from the lower window he took an exact observation, and noticed that the projectile was apparently stationary. Then rising and wiping his forehead, on which large drops of perspiration were standing, he put some figures on paper. Nicholl understood that the president was deducting from the terrestrial diameter the projectile's distance from the earth. He watched him anxiously.

No," exclaimed Barbicane, after some moments, "no, we are not falling! no, we are already more than 50,000 leagues from the earth. We have passed the point at which the projectile would have stopped if its speed had only been 12,000 yards at starting. We are still going up."

That is evident," replied Nicholl; "and we must conclude that our initial speed, under the power of the 400,000 pounds of gun-cotton, must have exceeded the required 12,000 yards. Now I can understand how, after thirteen minutes only, we met the second satellite, which gravitates round the earth at more than 2,000 leagues' distance."

And this explanation is the more probable," added Barbicane, "Because, in throwing off the water enclosed between its partition-breaks, the projectile found itself lightened of a considerable weight."

Just so," said Nicholl.

Ah, my brave Nicholl, we are saved!"

Very well then," said Michel Ardan quietly; "as we are safe, let us have breakfast."

Nicholl was not mistaken. The initial speed had been, very fortunately, much above that estimated by the Cambridge Observatory; but the Cambridge Observatory had nevertheless made a mistake.

The travelers, recovered from this false alarm, breakfasted merrily. If they ate a good deal, they talked more. Their confidence was greater after than before "the incident of the algebra."

Why should we not succeed?" said Michel Ardan; "why should we not arrive safely? We are launched; we have no obstacle before us, no stones in the way; the road is open, more so than that of a ship battling with the sea; more open than that of a balloon battling with the wind; and if a ship can reach its destination, a balloon go where it pleases, why cannot our projectile attain its end and aim?"

It will attain it," said Barbicane.

If only to do honor to the Americans," added Michel Ardan, "the only people who could bring such an enterprise to a happy termination, and the only one which could produce a President Barbicane. Ah, now we are no longer uneasy, I begin to think, What will become of us? We shall get right royally weary."

Barbicane and Nicholl made a gesture of denial.

But I have provided for the contingency, my friends," replied Michel; "you have only to speak, and I have chess, draughts, cards, and dominoes at your disposal; nothing is wanting but a billiard-table."

What!" exclaimed Barbicane; "you brought away such trifles?"

Certainly," replied Michel, "and not only to distract ourselves, but also with the laudable intention of endowing the Selenite smoking divans with them."

My friend," said Barbicane, "if the moon is inhabited, its inhabitants must have appeared some thousands of years before those of the earth, for we cannot doubt that their star is much older than ours. If then these Selenites have existed their hundreds of thousands of years, and if their brain is of the same organization of the human brain, they have already invented all that we have invented, and even what we may invent in future ages. They have nothing to learn from us, and we have everything to learn from them."

What!" said Michel; "you believe that they have artists like Phidias, Michael Angelo, or Raphael?"

Yes."

Poets like Homer, Virgil, Milton, Lamartine, and Hugo?"

I am sure of it."

Philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Kant?"

I have no doubt of it."

Scientific men like Archimedes, Euclid, Pascal, Newton?"

I could swear it."

Comic writers like Arnal, and photographers like-- like Nadar?"

Certain."

Then, friend Barbicane, if they are as strong as we are, and even stronger-- these Selenites-- why have they not tried to communicate with the earth? why have they not launched a lunar projectile to our terrestrial regions?"

Who told you that they have never done so?" said Barbicane seriously.

Indeed," added Nicholl, "it would be easier for them than for us, for two reasons; first, because the attraction on the moon's surface is six times less than on that of the earth, which would allow a projectile to rise more easily; secondly, because it would be enough to send such a projectile only at 8,000 leagues instead of 80,000, which would require the force of projection to be ten times less strong."

Then," continued Michel, "I repeat it, why have they not done it?"

And I repeat," said Barbicane; "who told you that they have not done it?"

When?"

Thousands of years before man appeared on earth."

And the projectile-- where is the projectile? I demand to see the projectile."

My friend," replied Barbicane, "the sea covers five-sixths of our globe. From that we may draw five good reasons for supposing that the lunar projectile, if ever launched, is now at the bottom of the Atlantic or the Pacific, unless it sped into some crevasse at that period when the crust of the earth was not yet hardened."

Old Barbicane," said Michel, "you have an answer for everything, and I bow before your wisdom. But there is one hypothesis that would suit me better than all the others, which is, the Selenites, being older than we, are wiser, and have not invented gunpowder."

At this moment Diana joined in the conversation by a sonorous barking. She was asking for her breakfast.

Ah!" said Michel Ardan, "in our discussion we have forgotten Diana and Satellite."

Immediately a good-sized pie was given to the dog, which devoured it hungrily.

Do you see, Barbicane," said Michel, "we should have made a second Noah's ark of this projectile, and borne with us to the moon a couple of every kind of domestic animal."

I dare say; but room would have failed us."

Oh!" said Michel, "we might have squeezed a little."

The fact is," replied Nicholl, "that cows, bulls, and horses, and all ruminants, would have been very useful on the lunar continent, but unfortunately the car could neither have been made a stable nor a shed."

Well, we might have at least brought a donkey, only a little donkey; that courageous beast which old Silenus loved to mount. I love those old donkeys; they are the least favored animals in creation; they are not only beaten while alive, but even after they are dead."

How do you make that out?" asked Barbicane. "Why," said Michel, "they make their skins into drums."

Barbicane and Nicholl could not help laughing at this ridiculous remark. But a cry from their merry companion stopped them. The latter was leaning over the spot where Satellite lay. He rose, saying:

My good Satellite is no longer ill."

Ah!" said Nicholl.

No," answered Michel, "he is dead! There," added he, in a piteous tone, "that is embarrassing. I much fear, my poor Diana, that you will leave no progeny in the lunar regions!"

Indeed the unfortunate Satellite had not survived its wound. It was quite dead. Michel Ardan looked at his friends with a rueful countenance.

One question presents itself," said Barbicane. "We cannot keep the dead body of this dog with us for the next forty-eight hours."

No! certainly not," replied Nicholl; "but our scuttles are fixed on hinges; they can be let down. We will open one, and throw the body out into space."

The president thought for some moments, and then said:

Yes, we must do so, but at the same time taking very great precautions."

Why?" asked Michel.

For two reasons which you will understand," answered Barbicane. "The first relates to the air shut up in the projectile, and of which we must lose as little as possible."

But we manufacture the air?"

Only in part. We make only the oxygen, my worthy Michel; and with regard to that, we must watch that the apparatus does not furnish the oxygen in too great a quantity; for an excess would bring us very serious physiological troubles. But if we make the oxygen, we do not make the azote, that medium which the lungs do not absorb, and which ought to remain intact; and that azote will escape rapidly through the open scuttles."

Oh! the time for throwing out poor Satellite?" said Michel.

Agreed; but we must act quickly."

And the second reason?" asked Michel.

The second reason is that we must not let the outer cold, which is excessive, penetrate the projectile or we shall be frozen to death."

But the sun?"

The sun warms our projectile, which absorbs its rays; but it does not warm the vacuum in which we are floating at this moment. Where there is no air, there is no more heat than diffused light; and the same with darkness; it is cold where the sun's rays do not strike direct. This temperature is only the temperature produced by the radiation of the stars; that is to say, what the terrestrial globe would undergo if the sun disappeared one day."

Which is not to be feared," replied Nicholl.

Who knows?" said Michel Ardan. "But, in admitting that the sun does not go out, might it not happen that the earth might move away from it?"

There!" said Barbicane, "there is Michel with his ideas."

And," continued Michel, "do we not know that in 1861 the earth passed through the tail of a comet? Or let us suppose a comet whose power of attraction is greater than that of the sun. The terrestrial orbit will bend toward the wandering star, and the earth, becoming its satellite, will be drawn such a distance that the rays of the sun will have no action on its surface."

That might happen, indeed," replied Barbicane, "but the consequences of such a displacement need not be so formidable as you suppose."

And why not?"

Because the heat and cold would be equalized on our globe. It has been calculated that, had our earth been carried along in its course by the comet of 1861, at its perihelion, that is, its nearest approach to the sun, it would have undergone a heat 28,000 times greater than that of summer.

But this heat, which is sufficient to evaporate the waters, would have formed a thick ring of cloud, which would have modified that excessive temperature; hence the compensation between the cold of the aphelion and the heat of the perihelion."

At how many degrees," asked Nicholl, "is the temperature of the planetary spaces estimated?"

Formerly," replied Barbicane, "it was greatly exagerated; but now, after the calculations of Fourier, of the French Academy of Science, it is not supposed to exceed 60@ Centigrade below zero."

Pooh!" said Michel, "that's nothing!"

It is very much," replied Barbicane; "the temperature which was observed in the polar regions, at Melville Island and Fort Reliance, that is 76@ Fahrenheit below zero."

If I mistake not," said Nicholl, "M. Pouillet, another savant, estimates the temperature of space at 250@ Fahrenheit below zero. We shall, however, be able to verify these calculations for ourselves."

Not at present; because the solar rays, beating directly upon our thermometer, would give, on the contrary, a very high temperature. But, when we arrive in the moon, during its fifteen days of night at either face, we shall have leisure to make the experiment, for our satellite lies in a vacuum."

What do you mean by a vacuum?" asked Michel. "Is it perfectly such?"

It is absolutely void of air."

And is the air replaced by nothing whatever?"

By the ether only," replied Barbicane.

And pray what is the ether?"

The ether, my friend, is an agglomeration of imponderable atoms, which, relatively to their dimensions, are as far removed from each other as the celestial bodies are in space. It is these atoms which, by their vibratory motion, produce both light and heat in the universe."

They now proceeded to the burial of Satellite. They had merely to drop him into space, in the same way that sailors drop a body into the sea; but, as President Barbicane suggested, they must act quickly, so as to lose as little as possible of that air whose elasticity would rapidly have spread it into space. The bolts of the right scuttle, the opening of which measured about twelve inches across, were carefully drawn, while Michel, quite grieved, prepared to launch his dog into space. The glass, raised by a powerful lever, which enabled it to overcome the pressure of the inside air on the walls of the projectile, turned rapidly on its hinges, and Satellite was thrown out. Scarcely a particle of air could have escaped, and the operation was so successful that later on Barbicane did not fear to dispose of the rubbish which encumbered the car.

New River at Grandview

Photos by Bob Kirchman

Disney Goes to the 1964 World's Fair

From dinosaurs to dancing children of the world, Disney artists had a field day creating animated figures for the fair. Small World and Carousel of Progress remain as popular attractions in Disney Parks. The creation of Disney animated creatures began with the giant squid in the movie 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and continues as park attractions are developed today.

Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Futurism of Walt Disney

Little House Mountain

A Wonderland in Rockbridge County, VA

The summit of Little House Mountain is a veritable garden.

Photos by bob Kirchman.

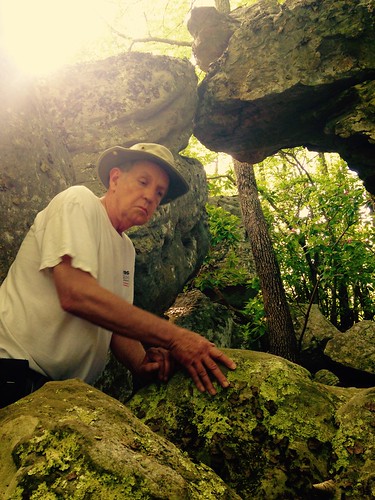

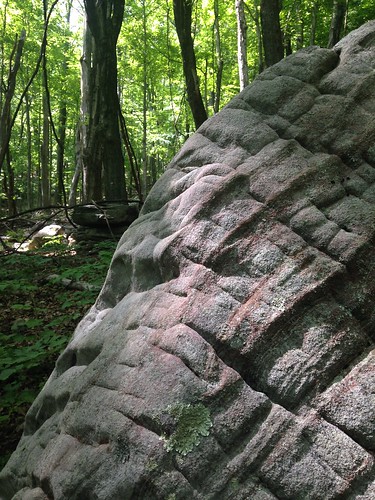

The Ruins of Cair Paravel

Rock Formations Inspire Imagination

At the summit of Little House Mountain are these wonderful rock formations that call to mind Narnia's Cair Paravel!

Photos by Bob Kirchman.

Sunset Over House Mountain

Photos by Bob Kirchman.

Man's First Act on the Moon

A reenactment of the Celebration of Communion by the Apollo 11 Astronauts.