Volume XV, Issue IV

The Place of Faith in Education

A Unique Perspective on the Issue from CIVITAS

Iris. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom: a good understanding have all they that do his commandments: his praise endureth for ever.” – Psalm 111:10

The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge: but fools despise wisdom and instruction.” – Proverbs 1:7

The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom: and the knowledge of the holy is understanding.” – Proverbs 9:10

Education is only adequate and worthy when it is itself religious… There is no possibility of neutrality… To be neutral concerning G-d is the same thing as to ignore Him… If children are brought up to have an understanding of life in which, in fact, there is no reference to G-d, you cannot correct the effect of that by speaking about G-d for a certain period of the day. Therefore our ideal for the children of our country is the ideal for truly religious education." -- William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury in 1942.

Here is a very interesting report from CIVITAS [1.], on The Place of Faith in Schools [click to read] by Professor David Conway. It adds a new dimension to the debate now raging in America between those who would impose a strictly secular criteria and those who consider Faith an essential component of learning.

[A] nation which draws into itself continuously, and not merely in its first beginnings, the inspiration of a religious faith and a religious purpose will increase its own vitality… Our own nation… has been inspired by a not ignoble notion of national duty to aid the oppressed – the persecuted Vaudois, the suffering slave, the oppressed nationality – and it has been most... characteristically national when it has most felt such inspiration…

We offend against the essence of the [English] nation if we emphasise its secularity, or regard it as merely an earthly unit for earthly purposes. Its tradition began its life at the breast of Christianity; and its development in time, through the centuries… has not been utterly way from its nursing mother… [I]n England our national tradition has been opposed to the idea of a merely secular society for secular purposes standing over against a separate religious society for religious purposes. Our practice has been in the main that of the single society, which if national is also religious, making public profession of Christianity in its solemn acts, and recognising religious instruction as part of its scheme of education." -- Ernest Barker, Cambridge Philosopher

Professor Conway Concludes: "All would stand to benefit from such committed forms of religious education in the country’s state-funded schools, not simply because it would be likely to improve the educational performance, behaviour and well-being of the nation’s schoolchildren. They would also all benefit because, I believe, only by continuing to provide it can this country be assured of remaining the independent and united liberal polity that it has for so long been and from whose continuing to be such all its diverse inhabitants would derive benefit, even those who do not share that faith or any other."

Capturing Light

My Talk at Natural Bridge

Walk about Zion, and go round about her: tell the towers thereof. Mark ye well her bulwarks, consider her palaces; that ye may tell it to the generation following. For this God is our God for ever and ever: he will be our guide even unto death.” – PSALM 48:12-14

I never tire of telling the story of Mohomony. That is what the Monacans called Virginia’s Natural Bridge. In their legend they faced a much larger force of Powhatans and prevailed because the bridge narrowed the attacking forces. The Monacans, fighting for wives and children behind them, overcame a much more powerful attacking force because they met them atop the bridge where an equal number of warriors faced them at any given time; constrained by the width of the bridge.

No doubt, the Monacans who fought in that battle would show young people the Natural Bridge and recount the wonder of Mohomony for them. This would be to them a story of Divine Deliverance just as the youth of Jerusalem would be encouraged to take note of their own history of Divine Deliverance. PSALM 48 ends with just such a charge!

I am giving a talk on the inspiration for my paintings at Natural Bridge. Part of it is a workshop for children where I give them black paper and white charcoal. I encourage them to look up at the bridge and remember the story. Then I guide them in drawing the light. It is fun to watch them draw light instead of just dark lines on white paper.

One little girl from South Carolina was particularly inspired by the project. She was seven years old and her mother proudly showed me some phone pictures of her work. She wanted to give me her capture of the bridge but I insisted that she give it to her mom and I would take a picture of it for myself! There are a few souls who’s IMAGO DEI extends to very early expression in art. I told her mom that she had a great treasure. Cherish her well!

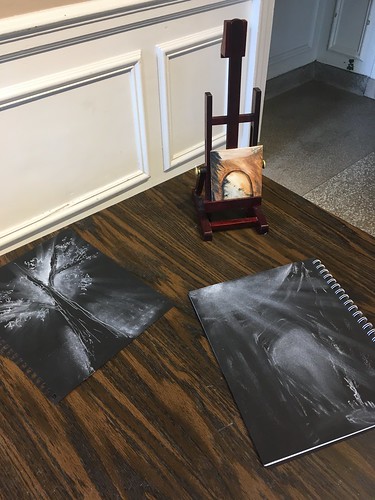

Here are my examples of 'Capturing Light' along with a painting by Savhanna Herndon for inspiration.

Demonstration of 'Capturing Light.' Photos by Bob Kirchman.

Mohomony

Natural Bridge as Seen from Below

Looking straight up at Mohomony from Cedar Creek.

Photo by Bob Kirchman

Homage to Willy Ferguson

Mural to Honor Staunton Metal Sculptor

Beginnings of the mural. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Our students from the Home School Coop have begun a mural that will honor the memory of Willy Ferguson, the man who created the giant watering can at the entrance to the city. Designed by Madeline Maas, the mural, which is in sight of the watering can, will feature bright sunflowers in the manner of Vincent van Gogh. Students will be working on the painting this week.

Students begin painting. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Willy Ferguson created Staunton's Watering Can Sculpture.

Photo by Bob Kirchman.

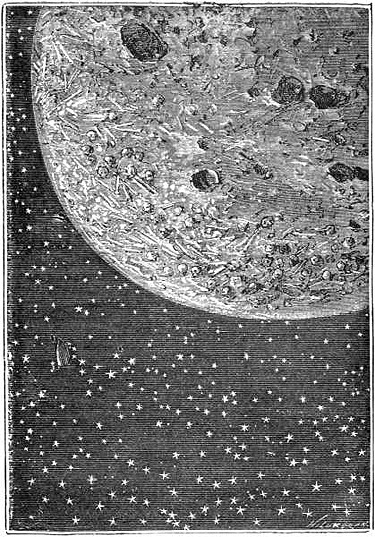

Round the Moon

By Jules Verne

CHAPTER VIII,

AT SEVENTY-EIGHT THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED AND FOURTEEN LEAGUES

What had happened? Whence the cause of this singular intoxication, the consequences of which might have been very disastrous? A simple blunder of Michel's, which, fortunately, Nicholl was able to correct in time.

After a perfect swoon, which lasted some minutes, the captain, recovering first, soon collected his scattered senses. Although he had breakfasted only two hours before, he felt a gnawing hunger, as if he had not eaten anything for several days. Everything about him, stomach and brain, were overexcited to the highest degree.

He got up and demanded from Michel a supplementary repast. Michel, utterly done up, did not answer.

Nicholl then tried to prepare some tea destined to help the absorption of a dozen sandwiches. He first tried to get some fire, and struck a match sharply. What was his surprise to see the sulphur shine with so extraordinary a brilliancy as to be almost unbearable to the eye. From the gas-burner which he lit rose a flame equal to a jet of electric light.

A revelation dawned on Nicholl's mind. That intensity of light, the physiological troubles which had arisen in him, the overexcitement of all his moral and quarrelsome faculties-- he understood all.

The oxygen!" he exclaimed.

And leaning over the air apparatus, he saw that the tap was allowing the colorless gas to escape freely, life-giving, but in its pure state producing the gravest disorders in the system. Michel had blunderingly opened the tap of the apparatus to the full.

Nicholl hastened to stop the escape of oxygen with which the atmosphere was saturated, which would have been the death of the travelers, not by suffocation, but by combustion. An hour later, the air less charged with it restored the lungs to their normal condition. By degrees the three friends recovered from their intoxication; but they were obliged to sleep themselves sober over their oxygen as a drunkard does over his wine.

When Michel learned his share of the responsibility of this incident, he was not much disconcerted. This unexpected drunkenness broke the monotony of the journey. Many foolish things had been said while under its influence, but also quickly forgotten.

And then," added the merry Frenchman, "I am not sorry to have tasted a little of this heady gas. Do you know, my friends, that a curious establishment might be founded with rooms of oxygen, where people whose system is weakened could for a few hours live a more active life. Fancy parties where the room was saturated with this heroic fluid, theaters where it should be kept at high pressure; what passion in the souls of the actors and spectators! what fire, what enthusiasm! And if, instead of an assembly only a whole people could be saturated, what activity in its functions, what a supplement to life it would derive. From an exhausted nation they might make a great and strong one, and I know more than one state in old Europe which ought to put itself under the regime of oxygen for the sake of its health!"

Michel spoke with so much animation that one might have fancied that the tap was still too open. But a few words from Barbicane soon shattered his enthusiasm.

That is all very well, friend Michel," said he, "but will you inform us where these chickens came from which have mixed themselves up in our concert?"

Those chickens?"

Yes."

Indeed, half a dozen chickens and a fine cock were walking about, flapping their wings and chattering.

Ah, the awkward things!" exclaimed Michel. "The oxygen has made them revolt."

But what do you want to do with these chickens?" asked Barbicane.

To acclimatize them in the moon, by Jove!"

Then why did you hide them?"

A joke, my worthy president, a simple joke, which has proved a miserable failure. I wanted to set them free on the lunar continent, without saying anything. Oh, what would have been your amazement on seeing these earthly-winged animals pecking in your lunar fields!"

You rascal, you unmitigated rascal," replied Barbicane, "you do not want oxygen to mount to the head. You are always what we were under the influence of the gas; you are always foolish!"

Ah, who says that we were not wise then?" replied Michel Ardan.

After this philosophical reflection, the three friends set about restoring the order of the projectile. Chickens and cock were reinstated in their coop. But while proceeding with this operation, Barbicane and his two companions had a most desired perception of a new phenomenon. From the moment of leaving the earth, their own weight, that of the projectile, and the objects it enclosed, had been subject to an increasing diminution.

If they could not prove this loss of the projectile, a moment would arrive when it would be sensibly felt upon themselves and the utensils and instruments they used.

It is needless to say that a scale would not show this loss; for the weight destined to weight the object would have lost exactly as much as the object itself; but a spring steelyard for example, the tension of which was independent of the attraction, would have given a just estimate of this loss.

We know that the attraction, otherwise called the weight, is in proportion to the densities of the bodies, and inversely as the squares of the distances. Hence this effect: If the earth had been alone in space, if the other celestial bodies had been suddenly annihilated, the projectile, according to Newton's laws, would weigh less as it got farther from the earth, but without ever losing its weight entirely, for the terrestrial attraction would always have made itself felt, at whatever distance.

But, in reality, a time must come when the projectile would no longer be subject to the law of weight, after allowing for the other celestial bodies whose effect could not be set down as zero. Indeed, the projectile's course was being traced between the earth and the moon. As it distanced the earth, the terrestrial attraction diminished: but the lunar attraction rose in proportion. There must come a point where these two attractions would neutralize each other: the projectile would possess weight no longer. If the moon's and the earth's densities had been equal, this point would have been at an equal distance between the two orbs. But taking the different densities into consideration, it was easy to reckon that this point would be situated at 47/60ths of the whole journey, i.e., at 78,514 leagues from the earth. At this point, a body having no principle of speed or displacement in itself, would remain immovable forever, being attracted equally by both orbs, and not being drawn more toward one than toward the other.

Now if the projectile's impulsive force had been correctly calculated, it would attain this point without speed, having lost all trace of weight, as well as all the objects within it. What would happen then? Three hypotheses presented themselves.

1. Either it would retain a certain amount of motion, and pass the point of equal attraction, and fall upon the moon by virtue of the excess of the lunar attraction over the terrestrial.

2. Or, its speed failing, and unable to reach the point of equal attraction, it would fall upon the moon by virtue of the excess of the lunar attraction over the terrestrial. 3. Or, lastly, animated with sufficient speed to enable it to reach the neutral point, but not sufficient to pass it, it would remain forever suspended in that spot like the pretended tomb of Mahomet, between the zenith and the nadir.

Such was their situation; and Barbicane clearly explained the consequences to his traveling companions, which greatly interested them. But how should they know when the projectile had reached this neutral point situated at that distance, especially when neither themselves, nor the objects enclosed in the projectile, would be any longer subject to the laws of weight?

Up to this time, the travelers, while admitting that this action was constantly decreasing, had not yet become sensible to its total absence.

But that day, about eleven o'clock in the morning, Nicholl having accidentally let a glass slip from his hand, the glass, instead of falling, remained suspended in the air.

Ah!" exclaimed Michel Ardan, "that is rather an amusing piece of natural philosophy."

And immediately divers other objects, firearms and bottles, abandoned to themselves, held themselves up as by enchantment. Diana too, placed in space by Michel, reproduced, but without any trick, the wonderful suspension practiced by Caston and Robert Houdin. Indeed the dog did not seem to know that she was floating in air.

The three adventurous companions were surprised and stupefied, despite their scientific reasonings.

They felt themselves being carried into the domain of wonders! they felt that weight was really wanting to their bodies. If they stretched out their arms, they did not attempt to fall. Their heads shook on their shoulders. Their feet no longer clung to the floor of the projectile. They were like drunken men having no stability in themselves.

Fancy has depicted men without reflection, others without shadow. But here reality, by the neutralizations of attractive forces, produced men in whom nothing had any weight, and who weighed nothing themselves.

Suddenly Michel, taking a spring, left the floor and remained suspended in the air, like Murillo's monk of the Cusine des Anges.

The two friends joined him instantly, and all three formed a miraculous "Ascension" in the center of the projectile.

Is it to be believed? is it probable? is it possible?" exclaimed Michel; "and yet it is so. Ah! if Raphael had seen us thus, what an `Assumption' he would have thrown upon canvas!"

The `Assumption' cannot last," replied Barbicane. "If the projectile passes the neutral point, the lunar attraction will draw us to the moon." "Then our feet will be upon the roof," replied Michel.

No," said Barbicane, "because the projectile's center of gravity is very low; it will only turn by degrees."

Then all our portables will be upset from top to bottom, that is a fact."

Calm yourself, Michel," replied Nicholl; "no upset is to be feared; not a thing will move, for the projectile's evolution will be imperceptible."

Just so," continued Barbicane; "and when it has passed the point of equal attraction, its base, being the heavier, will draw it perpendicularly to the moon; but, in order that this phenomenon should take place, we must have passed the neutral line."

Pass the neutral line," cried Michel; "then let us do as the sailors do when they cross the equator."

A slight side movement brought Michel back toward the padded side; thence he took a bottle and glasses, placed them "in space" before his companions, and, drinking merrily, they saluted the line with a triple hurrah. The influence of these attractions scarcely lasted an hour; the travelers felt themselves insensibly drawn toward the floor, and Barbicane fancied that the conical end of the projectile was varying a little from its normal direction toward the moon. By an inverse motion the base was approaching first; the lunar attraction was prevailing over the terrestrial; the fall toward the moon was beginning, almost imperceptibly as yet, but by degrees the attractive force would become stronger, the fall would be more decided, the projectile, drawn by its base, would turn its cone to the earth, and fall with ever-increasing speed on to the surface of the Selenite continent; their destination would then be attained. Now nothing could prevent the success of their enterprise, and Nicholl and Michel Ardan shared Barbicane's joy.

Then they chatted of all the phenomena which had astonished them one after the other, particularly the neutralization of the laws of weight. Michel Ardan, always enthusiastic, drew conclusions which were purely fanciful.

Ah, my worthy friends," he exclaimed, "what progress we should make if on earth we could throw off some of that weight, some of that chain which binds us to her; it would be the prisoner set at liberty; no more fatigue of either arms or legs. Or, if it is true that in order to fly on the earth's surface, to keep oneself suspended in the air merely by the play of the muscles, there requires a strength a hundred and fifty times greater than that which we possess, a simple act of volition, a caprice, would bear us into space, if attraction did not exist."

Just so," said Nicholl, smiling; "if we could succeed in suppressing weight as they suppress pain by anaesthesia, that would change the face of modern society!"

Yes," cried Michel, full of his subject, "destroy weight, and no more burdens!"

Well said," replied Barbicane; "but if nothing had any weight, nothing would keep in its place, not even your hat on your head, worthy Michel; nor your house, whose stones only adhere by weight; nor a boat, whose stability on the waves is only caused by weight; not even the ocean, whose waves would no longer be equalized by terrestrial attraction; and lastly, not even the atmosphere, whose atoms, being no longer held in their places, would disperse in space!"

That is tiresome," retorted Michel; "nothing like these matter-of-fact people for bringing one back to the bare reality."

But console yourself, Michel," continued Barbicane, "for if no orb exists from whence all laws of weight are banished, you are at least going to visit one where it is much less than on the earth."

The moon?"

Yes, the moon, on whose surface objects weigh six times less than on the earth, a phenomenon easy to prove."

And we shall feel it?" asked Michel.

Evidently, as two hundred pounds will only weigh thirty pounds on the surface of the moon."

And our muscular strength will not diminish?"

Not at all; instead of jumping one yard high, you will rise eighteen feet high."

But we shall be regular Herculeses in the moon!" exclaimed Michel.

Yes," replied Nicholl; "for if the height of the Selenites is in proportion to the density of their globe, they will be scarcely a foot high."

Lilliputians!" ejaculated Michel; "I shall play the part of Gulliver. We are going to realize the fable of the giants. This is the advantage of leaving one's own planet and over-running the solar world."

One moment, Michel," answered Barbicane; "if you wish to play the part of Gulliver, only visit the inferior planets, such as Mercury, Venus, or Mars, whose density is a little less than that of the earth; but do not venture into the great planets, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune; for there the order will be changed, and you will become Lilliputian."

And in the sun?"

In the sun, if its density is thirteen hundred and twenty-four thousand times greater, and the attraction is twenty-seven times greater than on the surface of our globe, keeping everything in proportion, the inhabitants ought to be at least two hundred feet high."

By Jove!" exclaimed Michel; "I should be nothing more than a pigmy, a shrimp!"

Gulliver with the giants," said Nicholl.

Just so," replied Barbicane.

And it would not be quite useless to carry some pieces of artillery to defend oneself."

Good," replied Nicholl; "your projectiles would have no effect on the sun; they would fall back upon the earth after some minutes."

That is a strong remark."

It is certain," replied Barbicane; "the attraction is so great on this enormous orb, that an object weighing 70,000 pounds on the earth would weigh but 1,920 pounds on the surface of the sun. If you were to fall upon it you would weigh-- let me see-- about 5,000 pounds, a weight which you would never be able to raise again."

The devil!" said Michel; "one would want a portable crane. However, we will be satisfied with the moon for the present; there at least we shall cut a great figure. We will see about the sun by and by."

CHAPTER IX, THE CONSEQUENCES OF A DEVIATION

Barbicane had now no fear of the issue of the journey, at least as far as the projectile's impulsive force was concerned; its own speed would carry it beyond the neutral line; it would certainly not return to earth; it would certainly not remain motionless on the line of attraction. One single hypothesis remained to be realized, the arrival of the projectile at its destination by the action of the lunar attraction.

It was in reality a fall of 8,296 leagues on an orb, it is true, where weight could only be reckoned at one sixth of terrestrial weight; a formidable fall, nevertheless, and one against which every precaution must be taken without delay.

These precautions were of two sorts, some to deaden the shock when the projectile should touch the lunar soil, others to delay the fall, and consequently make it less violent.

To deaden the shock, it was a pity that Barbicane was no longer able to employ the means which had so ably weakened the shock at departure, that is to say, by water used as springs and the partition breaks.

The partitions still existed, but water failed, for they could not use their reserve, which was precious, in case during the first days the liquid element should be found wanting on lunar soil.

And indeed this reserve would have been quite insufficient for a spring. The layer of water stored in the projectile at the time of starting upon their journey occupied no less than three feet in depth, and spread over a surface of not less than fifty-four square feet. Besides, the cistern did not contain one-fifth part of it; they must therefore give up this efficient means of deadening the shock of arrival. Happily, Barbicane, not content with employing water, had furnished the movable disc with strong spring plugs, destined to lessen the shock against the base after the breaking of the horizontal partitions. These plugs still existed; they had only to readjust them and replace the movable disc; every piece, easy to handle, as their weight was now scarcely felt, was quickly mounted.

The different pieces were fitted without trouble, it being only a matter of bolts and screws; tools were not wanting, and soon the reinstated disc lay on steel plugs, like a table on its legs. One inconvenience resulted from the replacing of the disc, the lower window was blocked up; thus it was impossible for the travelers to observe the moon from that opening while they were being precipitated perpendicularly upon her; but they were obliged to give it up; even by the side openings they could still see vast lunar regions, as an aeronaut sees the earth from his car.

This replacing of the disc was at least an hour's work. It was past twelve when all preparations were finished. Barbicane took fresh observations on the inclination of the projectile, but to his annoyance it had not turned over sufficiently for its fall; it seemed to take a curve parallel to the lunar disc. The orb of night shone splendidly into space, while opposite, the orb of day blazed with fire.

Their situation began to make them uneasy.

Are we reaching our destination?" said Nicholl.

Let us act as if we were about reaching it," replied Barbicane.

You are sceptical," retorted Michel Ardan. "We shall arrive, and that, too, quicker than we like."

This answer brought Barbicane back to his preparations, and he occupied himself with placing the contrivances intended to break their descent. We may remember the scene of the meeting held at Tampa Town, in Florida, when Captain Nicholl came forward as Barbicane's enemy and Michel Ardan's adversary. To Captain Nicholl's maintaining that the projectile would smash like glass, Michel replied that he would break their fall by means of rockets properly placed.

Thus, powerful fireworks, taking their starting-point from the base and bursting outside, could, by producing a recoil, check to a certain degree the projectile's speed. These rockets were to burn in space, it is true; but oxygen would not fail them, for they could supply themselves with it, like the lunar volcanoes, the burning of which has never yet been stopped by the want of atmosphere round the moon.

Barbicane had accordingly supplied himself with these fireworks, enclosed in little steel guns, which could be screwed on to the base of the projectile. Inside, these guns were flush with the bottom; outside, they protruded about eighteen inches. There were twenty of them. An opening left in the disc allowed them to light the match with which each was provided. All the effect was felt outside. The burning mixture had already been rammed into each gun. They had, then, nothing to do but raise the metallic buffers fixed in the base, and replace them by the guns, which fitted closely in their places.

This new work was finished about three o'clock, and after taking all these precautions there remained but to wait. But the projectile was perceptibly nearing the moon, and evidently succumbed to her influence to a certain degree; though its own velocity also drew it in an oblique direction. From these conflicting influences resulted a line which might become a tangent. But it was certain that the projectile would not fall directly on the moon; for its lower part, by reason of its weight, ought to be turned toward her.

Barbicane's uneasiness increased as he saw his projectile resist the influence of gravitation. The Unknown was opening before him, the Unknown in interplanetary space. The man of science thought he had foreseen the only three hypotheses possible-- the return to the earth, the return to the moon, or stagnation on the neutral line; and here a fourth hypothesis, big with all the terrors of the Infinite, surged up inopportunely. To face it without flinching, one must be a resolute savant like Barbicane, a phlegmatic being like Nicholl, or an audacious adventurer like Michel Ardan.

Conversation was started upon this subject. Other men would have considered the question from a practical point of view; they would have asked themselves whither their projectile carriage was carrying them. Not so with these; they sought for the cause which produced this effect.

So we have become diverted from our route," said Michel; "but why?"

I very much fear," answered Nicholl, "that, in spite of all precautions taken, the Columbiad was not fairly pointed. An error, however small, would be enough to throw us out of the moon's attraction."

Then they must have aimed badly?" asked Michel.

I do not think so," replied Barbicane. "The perpendicularity of the gun was exact, its direction to the zenith of the spot incontestible; and the moon passing to the zenith of the spot, we ought to reach it at the full. There is another reason, but it escapes me."

Are we not arriving too late?" asked Nicholl.

Too late?" said Barbicane.

Yes," continued Nicholl. "The Cambridge Observatory's note says that the transit ought to be accomplished in ninety-seven hours thirteen minutes and twenty seconds; which means to say, that sooner the moon will not be at the point indicated, and later it will have passed it."

True," replied Barbicane. "But we started the 1st of December, at thirteen minutes and twenty-five seconds to eleven at night; and we ought to arrive on the 5th at midnight, at the exact moment when the moon would be full; and we are now at the 5th of December. It is now half-past three in the evening; half-past eight ought to see us at the end of our journey. Why do we not arrive?"

Might it not be an excess of speed?" answered Nicholl; "for we know now that its initial velocity was greater than they supposed."

No! a hundred times, no!" replied Barbicane. "An excess of speed, if the direction of the projectile had been right, would not have prevented us reaching the moon. No, there has been a deviation. We have been turned out of our course."

By whom? by what?" asked Nicholl.

cannot say," replied Barbicane.

Very well, then, Barbicane," said Michel, "do you wish to know my opinion on the subject of finding out this deviation?"

Speak."

I would not give half a dollar to know it. That we have deviated is a fact. Where we are going matters little; we shall soon see. Since we are being borne along in space we shall end by falling into some center of attraction or other."

Michel Ardan's indifference did not content Barbicane. Not that he was uneasy about the future, but he wanted to know at any cost why his projectile had deviated.

But the projectile continued its course sideways to the moon, and with it the mass of things thrown out. Barbicane could even prove, by the elevations which served as landmarks upon the moon, which was only two thousand leagues distant, that its speed was becoming uniform-- fresh proof that there was no fall. Its impulsive force still prevailed over the lunar attraction, but the projectile's course was certainly bringing it nearer to the moon, and they might hope that at a nearer point the weight, predominating, would cause a decided fall.

The three friends, having nothing better to do, continued their observations; but they could not yet determine the topographical position of the satellite; every relief was leveled under the reflection of the solar rays.

They watched thus through the side windows until eight o'clock at night. The moon had grown so large in their eyes that it filled half of the firmament. The sun on one side, and the orb of night on the other, flooded the projectile with light.

At that moment Barbicane thought he could estimate the distance which separated them from their aim at no more than 700 leagues. The speed of the projectile seemed to him to be more than 200 yards, or about 170 leagues a second. Under the centripetal force, the base of the projectile tended toward the moon; but the centrifugal still prevailed; and it was probable that its rectilineal course would be changed to a curve of some sort, the nature of which they could not at present determine.

Barbicane was still seeking the solution of his insoluble problem. Hours passed without any result.

The projectile was evidently nearing the moon, but it was also evident that it would never reach her. As to the nearest distance at which it would pass her, that must be the result of two forces, attraction and repulsion, affecting its motion.

I ask but one thing," said Michel; "that we may pass near enough to penetrate her secrets."

Cursed be the thing that has caused our projectile to deviate from its course," cried Nicholl.

And, as if a light had suddenly broken in upon his mind, Barbicane answered, "Then cursed be the meteor which crossed our path."

What?" said Michel Ardan.

What do you mean?" exclaimed Nicholl.

I mean," said Barbicane in a decided tone, "I mean that our deviation is owing solely to our meeting with this erring body."

But it did not even brush us as it passed," said Michel.

What does that matter? Its mass, compared to that of our projectile, was enormous, and its attraction was enough to influence our course."

So little?" cried Nicholl.

Yes, Nicholl; but however little it might be," replied Barbicane, "in a distance of 84,000 leagues, it wanted no more to make us miss the moon."

CHAPTER X, THE OBSERVERS OF THE MOON

Barbicane had evidently hit upon the only plausible reason of this deviation. However slight it might have been, it had sufficed to modify the course of the projectile. It was a fatality. The bold attempt had miscarried by a fortuitous circumstance; and unless by some exceptional event, they could now never reach the moon's disc.

Would they pass near enough to be able to solve certain physical and geological questions until then insoluble? This was the question, and the only one, which occupied the minds of these bold travelers. As to the fate in store for themselves, they did not even dream of it.

But what would become of them amid these infinite solitudes, these who would soon want air? A few more days, and they would fall stifled in this wandering projectile. But some days to these intrepid fellows was a century; and they devoted all their time to observe that moon which they no longer hoped to reach.

The distance which had then separated the projectile from the satellite was estimated at about two hundred leagues. Under these conditions, as regards the visibility of the details of the disc, the travelers were farther from the moon than are the inhabitants of earth with their powerful telescopes.

Indeed, we know that the instrument mounted by Lord Rosse at Parsonstown, which magnifies 6,500 times, brings the moon to within an apparent distance of sixteen leagues. And more than that, with the powerful one set up at Long's Peak, the orb of night, magnified 48,000 times, is brought to within less than two leagues, and objects having a diameter of thirty feet are seen very distinctly. So that, at this distance, the topographical details of the moon, observed without glasses, could not be determined with precision. The eye caught the vast outline of those immense depressions inappropriately called "seas," but they could not recognize their nature. The prominence of the mountains disappeared under the splendid irradiation produced by the reflection of the solar rays. The eye, dazzled as if it was leaning over a bath of molten silver, turned from it involuntarily; but the oblong form of the orb was quite clear. It appeared like a gigantic egg, with the small end turned toward the earth. Indeed the moon, liquid and pliable in the first days of its formation, was originally a perfect sphere; but being soon drawn within the attraction of the earth, it became elongated under the influence of gravitation. In becoming a satellite, she lost her native purity of form; her center of gravity was in advance of the center of her figure; and from this fact some savants draw the conclusion that the air and water had taken refuge on the opposite surface of the moon, which is never seen from the earth. This alteration in the primitive form of the satellite was only perceptible for a few moments.

The distance of the projectile from the moon diminished very rapidly under its speed, though that was much less than its initial velocity-- but eight or nine times greater than that which propels our express trains. The oblique course of the projectile, from its very obliquity, gave Michel Ardan some hopes of striking the lunar disc at some point or other. He could not think that they would never reach it. No! he could not believe it; and this opinion he often repeated. But Barbicane, who was a better judge, always answered him with merciless logic.

No, Michel, no! We can only reach the moon by a fall, and we are not falling. The centripetal force keeps us under the moon's influence, but the centrifugal force draws us irresistibly away from it."

This was said in a tone which quenched Michel Ardan's last hope.

The portion of the moon which the projectile was nearing was the northern hemisphere, that which the selenographic maps place below; for these maps are generally drawn after the outline given by the glasses, and we know that they reverse the objects. Such was the Mappa Selenographica of Boeer and Moedler which Barbicane consulted. This northern hemisphere presented vast plains, dotted with isolated mountains.

At midnight the moon was full. At that precise moment the travelers should have alighted upon it, if the mischievous meteor had not diverted their course. The orb was exactly in the condition determined by the Cambridge Observatory. It was mathematically at its perigee, and at the zenith of the twenty-eighth parallel. An observer placed at the bottom of the enormous Columbiad, pointed perpendicularly to the horizon, would have framed the moon in the mouth of the gun. A straight line drawn through the axis of the piece would have passed through the center of the orb of night. It is needless to say, that during the night of the 5th-6th of December, the travelers took not an instant's rest. Could they close their eyes when so near this new world? No! All their feelings were concentrated in one single thought:-- See! Representatives of the earth, of humanity, past and present, all centered in them! It is through their eyes that the human race look at these lunar regions, and penetrate the secrets of their satellite! A strange emotion filled their hearts as they went from one window to the other. Their observations, reproduced by Barbicane, were rigidly determined. To take them, they had glasses; to correct them, maps.

As regards the optical instruments at their disposal, they had excellent marine glasses specially constructed for this journey. They possessed magnifying powers of 100. They would thus have brought the moon to within a distance (apparent) of less than 2,000 leagues from the earth. But then, at a distance which for three hours in the morning did not exceed sixty-five miles, and in a medium free from all atmospheric disturbances, these instruments could reduce the lunar surface to within less than 1,500 yards!

(to be continued)

Volume XII, Issue XIIIc

PONTIFUS, The Bridge Builder's Tale

Copyright © 2017, The Kirchman Studio, all rights reserved

Table of Contents, Click to Enter:

Prequil: The Reckless Engineer

PONTIFUS, The Bridge Builder's Tale in Three Parts

Book 1: Dinner Stop at the End of the World

Book 2: Zimmerman's Folly

Book 3: Little House at the End of the World

NOVUS VIA, A Story of the More Perfect Way

Book 1: A Guide to the 2059/2060 World's Fair

Book 2: The Long Road Home

Book 3: The Road to Damascus

CORVINUS, A Story of Three Brothers and Their Rise to Power

Book 1: The Brothers CORVINUS

Book 2: Ascent to Power

Book 3: Behold the Man

APOLLONIUS, A Journey to a World Unseen

JOSIAH, A Time for Healing

The Gift Horse, A Short Story

Stones of Remembrance, A Short Story

ZIMMERLOOPTM, Travel in the Year 2059

Droplets

Photos by Bob Kirchman