Volume XI, Issue XXVII

If there was anything that bothered Rupert Zimmerman it was 'impossibility' created solely by bureaucratic convolutions. When the family packed in the car during his youth to visit the extended family in Michigan, they were inevitably faced with the Breezewood Interchange on Interstate Seventy. On Summer road trips the mighty highway's brief diversion to the old Lincoln highway resulted in gargantuan traffic jams, boiling radiators and often as many boiling tempers. Zimmerman's father REFUSED to stop at the roadside businesses who's continual lobbying fended off many a reasonable attempt to build the connection.

The lack of a connection was originally a byproduct of the funding legislation that allowed the Interstate highways to be built. Highways without tolls received the 90% Federal funding and tolls were permitted in special circumstances if they were needed to retire the bonds the state issued to build the road, but the Pennsylvania Turnpike had been built depending on the toll revenue and the Turnpike Authority was going to use ongoing tolls to support operations and maintenance of the facility. Interstate Seventy from Maryland to the Turnpike had been built by using the standard funding formula but Federal funds for the connection to the turnpike would only be given if the Turnpike became a freeway atfer the bonds were retired.

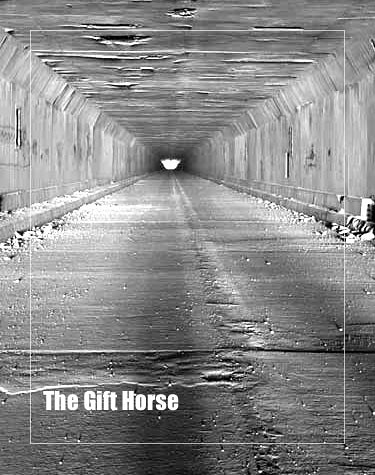

Penndot would not commit the entire amount of funding to complete the interchange, so it languished as a grade intersection onto US Thirty for decades. Service businesses rose and fell, but all considered the 'permenant' detour of Interstate Seventy crucial to their continued viability. The Turnpike Authority relocated the road around the Sideling Hill Tunnel, which they abandoned. This created a rather awkward interchange where you crossed the road you WANTED to be on by an overpass on your way to US 30 where you would double back to take the road further.

The whole scenario seemed to be taken from the age of competing railroads in the Nineteenth Century where rival roads spurned each other at what engineers would consider logical connecting points. As Rupert Zimmerman connected continents in the later part of the Twenty-first Century, the roads in Breezewood remained separated. Indeed, one would have laughed at the notion that they EVER would be connected.

But now the continents were connected. Indeed it had taken some hard negotiations and the infusion of Zimmerman money to connect Hokkaido, Japan's Northernmost Island, to the Asian mainland. The Completion of the Pan-American Highway through guerilla infested Central America was a similar challenge. Elizabeth Zimmerman O'Malley became known for her skills as a negotiator as the world was brought together. As the Zimmerman clan cut the ribbon for the new Americas Connector and rode through the tunnel under the now somewhat antiquated Panama Canal, it seemed that there was no obstacle too great, no river too wide, no mountain to high... but then there was Breezewood!

Indeed, the task of joining continents and its successful completion left Rupert Zimmerman with time on his hands. In his complex at Wales, scores of young apprentices peered into computer screens seeking to smooth the world's traffic flow. Zimmerman silently chuckled at the thought, passed along to him that you were really old when your colleagues were young enough to be your children. "Hah!," the old man thought as he walked past the office of his granddaughter, who was running the great bridge's operation now. Rupert's mind wandered to the time when his little daughter Elizabeth sat at a little table beside his drawing ponies and princesses.

Working with young people kept you young. That was what Zimmerman's experience told him anyway. For centuries father and mother had taught the skills of life to their children, who in turn taught their children. In relatively modern times the task had been relegated to 'experts' residing in the great universities. Sadly, much of the world's distress could be traced to ideas such as Marxism that flourished in the halls of academia long after they had failed as actual methods of governance. Zimmerman's young friends, the Greenes were pioneering a new interaction of academy connected to the world; one that did not isolate itself in ivory towers.

But as Zimmerman walked through the 'Labyrinth of Exile,' as he called his complex at Wales, the thought washed over him that he really was unnecessary now. He walked to the stairs and proceeded to the roof of the complex's tallest tower. He thought of the Patriarch David, Israel's great warrior-king. His undoing had begun on a rooftop. Rupert needed to stay out of his daughter's way... and now he needed to stay out of the way of his granddaughter, but firmly convinced that: "The devil find's work for idle hands," that thought propelled his hasty retreat from the rooftop. He stopped at the office of a young engineer and asked him to pull up some map images. He was not at all surprised by the top entry that came up in unfinished highway connections. It had remained so for decades. Rupert Zimmerman set is mind on Breezewood!

*******

His reception in Panama had been far warmer, Zimmerman thought, than the one he received in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. After several days of being pushed around through various offices of Penndot, Zimmerman had an audience with the Governor. Presenting her with a complete proposal of what Zimmerman Bridge and Highway would reconstruct the interchange for, he then handed her a cheque for the entire amount plus twenty per-cent for the inevitable overruns. The funds were clearly designated and the contract printed on the back of the cheque made it impossible for the funds to be diverted without a substantial penalty.

For years, a cartel of Breezewood businesses had successfully thwarted any effort to close the gap. Now they created a charge that Zimmerman was redistributing his own funds to line his own pockets! Even as the old man set up a trust to pay for 'substantial decreases in hospitality revenue,' Breezewood's lawyers lined their own pockets creating even more trumped-up charges to stall the project. Zimmerman rented a suite in one of Breezewood's hotels and made a show of having his breakfast at Perkin's or any number of Breezewood establishments. Though the old man graciously lobbied for his proposal, the local anger only intensified. There was an assassination attempt. After a bullet lodged in the wall of the pancake house behind the great builder, Pat and Elizabeth begged him to come home.

Panama and Nicaragua had been a breeze, compared to Breezewood," the old man thought. But after the assassination attempt, Penndot quickly and quietly awarded the contract for the Beezewood Connection to J. D. Eckman in Atglen, Pennsylvania. Slowly, the planning and construction began. Zimmerman admired the work of Eckman bescause they had pioneered some bridge jacking techniques. In decades past, the bridge carrying interstate 295 across the Christina River in Wilmington, Delaware had sunk on its pilings because of improperly stored sand piles at its pilings. Eckman brought in an innovative jacking system allowing the compromised pilings to be rebuilt. The bridge remained open even as its supporting structure was completely replaced.

Now the firm installed a prefabricated flyover to connect the interchange on the old section of turnpike to Interstate Seventy. Prefabrication was necessary because the 'cartel' had lobbied into place a set of 'environmental' regulations that made on-site construction impossible. Six months after permits were finally pulled, drivers sped from the interstate onto the turnpike. In the months that followed, Zimmerman's accountants held their breath, expecting a slew of lost revenue claims on the trust fund. As it turned out, Breezewood revenues actually increased. The few attempts to 'prove' otherwise and tap the fund were pretty quickly found out and prosecuted.

Zimmerman himself did not attend the opening ceremonies. He was to those outside of his circle of family and friends, seen as quite a recluse now, though his children and grandchildren would beg to differ. He DID drive through the connector, months later, in a Toyota. Three generations of Zimmerman family rode with him in the car as they drove from Virginia to Michigan.

The rebuilt Breezewood Interchange.

Copyright © 2016, The Kirchman Studio, all rights reserved