Volume XII, Issue XVIII

Phantasies

By George MacDonald, Chapter 12

Chained is the Spring. The night-wind bold

Blows over the hard earth;

Time is not more confused and cold,

Nor keeps more wintry mirth.

Yet blow, and roll the world about;

Blow, Time--blow, winter's Wind!

Through chinks of Time, heaven peepeth out,

And Spring the frost behind."

~ G. E. M.

They who believe in the influences of the stars over the fates of men, are, in feeling at least, nearer the truth than they who regard the heavenly bodies as related to them merely by a common obedience to an external law. All that man sees has to do with man. Worlds cannot be without an intermundane relationship. The community of the centre of all creation suggests an interradiating connection and dependence of the parts. Else a grander idea is conceivable than that which is already imbodied. The blank, which is only a forgotten life, lying behind the consciousness, and the misty splendour, which is an undeveloped life, lying before it, may be full of mysterious revelations of other connexions with the worlds around us, than those of science and poetry. No shining belt or gleaming moon, no red and green glory in a self-encircling twin-star, but has a relation with the hidden things of a man's soul, and, it may be, with the secret history of his body as well. They are portions of the living house wherein he abides.

Through the realms of the monarch Sun

Creeps a world, whose course had begun,

On a weary path with a weary pace,

Before the Earth sprang forth on her race:

But many a time the Earth had sped

Around the path she still must tread,

Ere the elder planet, on leaden wing,

Once circled the court of the planet's king.

There, in that lonely and distant star,

The seasons are not as our seasons are;

But many a year hath Autumn to dress

The trees in their matron loveliness;

As long hath old Winter in triumph to go

O'er beauties dead in his vaults below;

And many a year the Spring doth wear

Combing the icicles from her hair;

And Summer, dear Summer, hath years of June,

With large white clouds, and cool showers at noon:

And a beauty that grows to a weight like grief,

Till a burst of tears is the heart's relief.

Children, born when Winter is king,

May never rejoice in the hoping Spring;

Though their own heart-buds are bursting with joy,

And the child hath grown to the girl or boy;

But may die with cold and icy hours

Watching them ever in place of flowers.

And some who awake from their primal sleep,

When the sighs of Summer through forests creep,

Live, and love, and are loved again;

Seek for pleasure, and find its pain;

Sink to their last, their forsaken sleeping,

With the same sweet odours around them creeping.

Now the children, there, are not born as the children are born in worlds nearer to the sun. For they arrive no one knows how. A maiden, walking alone, hears a cry: for even there a cry is the first utterance; and searching about, she findeth, under an overhanging rock, or within a clump of bushes, or, it may be, betwixt gray stones on the side of a hill, or in any other sheltered and unexpected spot, a little child. This she taketh tenderly, and beareth home with joy, calling out, "Mother, mother"--if so be that her mother lives--"I have got a baby--I have found a child!" All the household gathers round to see;--"Where is it? What is it like? Where did you find it?" and such-like questions, abounding. And thereupon she relates the whole story of the discovery; for by the circumstances, such as season of the year, time of the day, condition of the air, and such like, and, especially, the peculiar and never-repeated aspect of the heavens and earth at the time, and the nature of the place of shelter wherein it is found, is determined, or at least indicated, the nature of the child thus discovered. Therefore, at certain seasons, and in certain states of the weather, according, in part, to their own fancy, the young women go out to look for children. They generally avoid seeking them, though they cannot help sometimes finding them, in places and with circumstances uncongenial to their peculiar likings. But no sooner is a child found, than its claim for protection and nurture obliterates all feeling of choice in the matter. Chiefly, however, in the season of summer, which lasts so long, coming as it does after such long intervals; and mostly in the warm evenings, about the middle of twilight; and principally in the woods and along the river banks, do the maidens go looking for children just as children look for flowers. And ever as the child grows, yea, more and more as he advances in years, will his face indicate to those who understand the spirit of Nature, and her utterances in the face of the world, the nature of the place of his birth, and the other circumstances thereof; whether a clear morning sun guided his mother to the nook whence issued the boy's low cry; or at eve the lonely maiden (for the same woman never finds a second, at least while the first lives) discovers the girl by the glimmer of her white skin, lying in a nest like that of the lark, amid long encircling grasses, and the upward-gazing eyes of the lowly daisies; whether the storm bowed the forest trees around, or the still frost fixed in silence the else flowing and babbling stream.

After they grow up, the men and women are but little together. There is this peculiar difference between them, which likewise distinguishes the women from those of the earth. The men alone have arms; the women have only wings. Resplendent wings are they, wherein they can shroud themselves from head to foot in a panoply of glistering glory. By these wings alone, it may frequently be judged in what seasons, and under what aspects, they were born. From those that came in winter, go great white wings, white as snow; the edge of every feather shining like the sheen of silver, so that they flash and glitter like frost in the sun. But underneath, they are tinged with a faint pink or rose-colour. Those born in spring have wings of a brilliant green, green as grass; and towards the edges the feathers are enamelled like the surface of the grass-blades. These again are white within. Those that are born in summer have wings of a deep rose-colour, lined with pale gold. And those born in autumn have purple wings, with a rich brown on the inside. But these colours are modified and altered in all varieties, corresponding to the mood of the day and hour, as well as the season of the year; and sometimes I found the various colours so intermingled, that I could not determine even the season, though doubtless the hieroglyphic could be deciphered by more experienced eyes. One splendour, in particular, I remember--wings of deep carmine, with an inner down of warm gray, around a form of brilliant whiteness. She had been found as the sun went down through a low sea-fog, casting crimson along a broad sea-path into a little cave on the shore, where a bathing maiden saw her lying. But though I speak of sun and fog, and sea and shore, the world there is in some respects very different from the earth whereon men live. For instance, the waters reflect no forms. To the unaccustomed eye they appear, if undisturbed, like the surface of a dark metal, only that the latter would reflect indistinctly, whereas they reflect not at all, except light which falls immediately upon them. This has a great effect in causing the landscapes to differ from those on the earth. On the stillest evening, no tall ship on the sea sends a long wavering reflection almost to the feet of him on shore; the face of no maiden brightens at its own beauty in a still forest-well. The sun and moon alone make a glitter on the surface. The sea is like a sea of death, ready to ingulf and never to reveal: a visible shadow of oblivion. Yet the women sport in its waters like gorgeous sea-birds. The men more rarely enter them. But, on the contrary, the sky reflects everything beneath it, as if it were built of water like ours. Of course, from its concavity there is some distortion of the reflected objects; yet wondrous combinations of form are often to be seen in the overhanging depth. And then it is not shaped so much like a round dome as the sky of the earth, but, more of an egg-shape, rises to a great towering height in the middle, appearing far more lofty than the other. When the stars come out at night, it shows a mighty cupola, "fretted with golden fires," wherein there is room for all tempests to rush and rave.

One evening in early summer, I stood with a group of men and women on a steep rock that overhung the sea. They were all questioning me about my world and the ways thereof. In making reply to one of their questions, I was compelled to say that children are not born in the Earth as with them. Upon this I was assailed with a whole battery of inquiries, which at first I tried to avoid; but, at last, I was compelled, in the vaguest manner I could invent, to make some approach to the subject in question. Immediately a dim notion of what I meant, seemed to dawn in the minds of most of the women. Some of them folded their great wings all around them, as they generally do when in the least offended, and stood erect and motionless. One spread out her rosy pinions, and flashed from the promontory into the gulf at its foot. A great light shone in the eyes of one maiden, who turned and walked slowly away, with her purple and white wings half dispread behind her. She was found, the next morning, dead beneath a withered tree on a bare hill-side, some miles inland. They buried her where she lay, as is their custom; for, before they die, they instinctively search for a spot like the place of their birth, and having found one that satisfies them, they lie down, fold their wings around them, if they be women, or cross their arms over their breasts, if they are men, just as if they were going to sleep; and so sleep indeed. The sign or cause of coming death is an indescribable longing for something, they know not what, which seizes them, and drives them into solitude, consuming them within, till the body fails. When a youth and a maiden look too deep into each other's eyes, this longing seizes and possesses them; but instead of drawing nearer to each other, they wander away, each alone, into solitary places, and die of their desire. But it seems to me, that thereafter they are born babes upon our earth: where, if, when grown, they find each other, it goes well with them; if not, it will seem to go ill. But of this I know nothing. When I told them that the women on the Earth had not wings like them, but arms, they stared, and said how bold and masculine they must look; not knowing that their wings, glorious as they are, are but undeveloped arms.

But see the power of this book, that, while recounting what I can recall of its contents, I write as if myself had visited the far-off planet, learned its ways and appearances, and conversed with its men and women. And so, while writing, it seemed to me that I had. The book goes on with the story of a maiden, who, born at the close of autumn, and living in a long, to her endless winter, set out at last to find the regions of spring; for, as in our earth, the seasons are divided over the globe. It begins something like this:

She watched them dying for many a day,

Dropping from off the old trees away,

One by one; or else in a shower

Crowding over the withered flower

For as if they had done some grievous wrong,

The sun, that had nursed them and loved them so long,

Grew weary of loving, and, turning back,

Hastened away on his southern track;

And helplessly hung each shrivelled leaf,

Faded away with an idle grief.

And the gusts of wind, sad Autumn's sighs,

Mournfully swept through their families;

Casting away with a helpless moan

All that he yet might call his own,

As the child, when his bird is gone for ever,

Flingeth the cage on the wandering river.

And the giant trees, as bare as Death,

Slowly bowed to the great Wind's breath;

And groaned with trying to keep from groaning

Amidst the young trees bending and moaning.

And the ancient planet's mighty sea

Was heaving and falling most restlessly,

And the tops of the waves were broken and white,

Tossing about to ease their might;

And the river was striving to reach the main,

And the ripple was hurrying back again.

Nature lived in sadness now;

Sadness lived on the maiden's brow,

As she watched, with a fixed, half-conscious eye,

One lonely leaf that trembled on high,

Till it dropped at last from the desolate bough--

Sorrow, oh, sorrow! 'tis winter now.

And her tears gushed forth, though it was but a leaf,

For little will loose the swollen fountain of grief:

When up to the lip the water goes,

It needs but a drop, and it overflows.

Oh! many and many a dreary year

Must pass away ere the buds appear:

Many a night of darksome sorrow

Yield to the light of a joyless morrow,

Ere birds again, on the clothed trees

, Shall fill the branches with melodies.

She will dream of meadows with wakeful streams;

Of wavy grass in the sunny beams;

Of hidden wells that soundless spring,

Hoarding their joy as a holy thing;

Of founts that tell it all day long

To the listening woods, with exultant song;

She will dream of evenings that die into nights,

Where each sense is filled with its own delights,

And the soul is still as the vaulted sky,

Lulled with an inner harmony;

And the flowers give out to the dewy night,

Changed into perfume, the gathered light;

And the darkness sinks upon all their host,

Till the sun sail up on the eastern coast--

She will wake and see the branches bare,

Weaving a net in the frozen air.

The story goes on to tell how, at last, weary with wintriness, she travelled towards the southern regions of her globe, to meet the spring on its slow way northwards; and how, after many sad adventures, many disappointed hopes, and many tears, bitter and fruitless, she found at last, one stormy afternoon, in a leafless forest, a single snowdrop growing betwixt the borders of the winter and spring. She lay down beside it and died. I almost believe that a child, pale and peaceful as a snowdrop, was born in the Earth within a fixed season from that stormy afternoon.

(to be continued)

Building Bridges

A history of bridge building.

PONTIFUS, The Bridge Builder's Tale

[click to read]

The History of Serial Fiction

Serials have existed in fiction for a very long time. Books were expensive back in the 19th century, so they were printed in installments in order to keep the price low. Charles Dickens, often heralded as one of the greatest early self-publishers, was also one of the most successful writers of serialized fiction. Another big name, Alexandre Dumas, was a very prolific serial novelist, publishing both The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers in serial format. In fact, serialization worked so well, it was considered the way to go by popular authors during the time." -- Samantha Warren

THYME Magazine presents, in serial form, the story of a man who challenged the proposition that something he wanted to achieve was "impossible." Based on history, depicted in the future, Pontifus is a tale of human triumph in the face of challenges such as face us today. (read more)

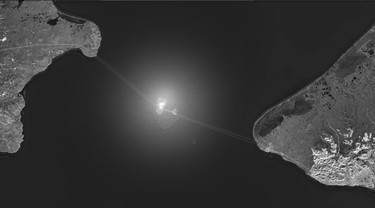

Sunlight reflects from the biosphere domes of Big Diomede in this photograph of the Bering Strait Bridge from space.

The twin spans of the Bering Strait Bridge. The original span (closest) is the Charles Alton Ellis Memorial Bridge. The second span is the Joseph Baermann Strauss Memorial Bridge.

The twin spans stretching to the West and Asia.

Alaska A2.

Copyright © 2017, The Kirchman Studio, all rights reserved

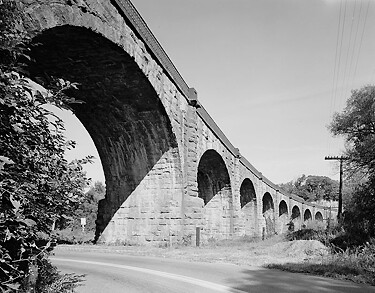

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Stone Bridges Built to Endure

The Valley Railroad, a branch of the Baltimore and Ohio, once ran all the way to Lexington, Virginia crossing this fine stone bridge. Photos by Bob Kirchman.

Although American railroads became known for wooden trestles and iron bridges, it is worth noting that the engineers of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad built fine stone bridges with smooth roman arches in the early days of the railroad. Two particularly fine examples are this bridge near Staunton, Virginia and the Thomas Viaduct on the road between Baltimore and Washington DC which still carries trains today.

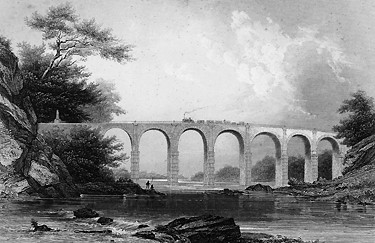

The Thomas Viaduct spans the Patapsco River and Patapsco Valley between Relay and Elkridge, Maryland, USA. It was commissioned by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; built between July 4, 1833, and July 4, 1835; and named for Philip E. Thomas, the company's first president.

At its completion, the Thomas Viaduct was the largest bridge in the United States and the country's first multi-span masonry railroad bridge to be built on a curve. It remains the world's oldest multiple arched stone railroad bridge. In 1964, it was designated as a National Historic Landmark.

The viaduct is now owned and operated by CSX Transportation and still in use today, making it one of the oldest railroad bridges still in service.

This Roman-arch stone bridge is divided into eight spans. It was designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, II, then B and O's assistant engineer and later its chief engineer. The main design problem to overcome was that of constructing such a large bridge on a curve. The design called for several variations in span and pier widths between the opposite sides of the structure. This problem was solved by having the lateral pier faces laid out on radial lines, making the piers essentially wedge-shaped and fitted to the 4-degree curve.

The viaduct was built by John McCartney of Ohio, who received the contract after completing the Patterson Viaduct. Caspar Wever, the railroad's chief of construction, supervised the work.

The span of the viaduct is 612 feet (187 m) long; the individual arches are roughly 58 feet (18 m) in span, with a height of 59 feet (18 m) from the water level to the base of the rail. The width at the top of the spandrel wall copings is 26 feet 4 inches (8 m). The bridge is constructed using a rough-dressed Maryland granite ashlar from Patapsco River quarries, known as Woodstock granite.[6] A wooden-floored walkway built for pedestrian and railway employee use is four feet wide and supported by cast iron brackets and edged with ornamental cast iron railings. The viaduct contains 24,476 cubic yards (18,713 m3) of masonry and cost $142,236.51, an estimated $2,769,917.36 in 2007 dollars. [Wikipedia]

The Thomas Viaduct across the Patapsco River. Library of Congress Photo. [1.]

Riding Railroading's Romantic Beginnings

Wind Power on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

AEolus sails down the Baltimore and Ohio tracks. From the Collections of the B and O Railroad Museum, used with permission.

A recent CSX Transportation radio spot invites canines in cars to "ride the wind, doggies!" It is a reference to the open roads created by CSX trains taking freight off the highways and a doggie's desire to ride in a car with his head sticking out of the open window. Railroading's early days briefly offered another opportunity to "ride the wind" as a unique experiment in motive power took place on America's first operating rail line.

In the early days of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the motive power was provided by horses. The carriages were pulled along the tracks by fine animals selected for this purpose. The building that housed stables and a blacksmith shop in Ellicott's Mills still stands. But horsepower would soon become a standard instead of a literal fact. Peter Cooper's small locomotive with its upright boiler would define the future of railroading. Still, there was a brief period in railroad history where passengers could literally ride the wind.

Evan Thomas of Baltimore constructed an experimental wicker car with a sail which he named the "AEolus." When there was enough wind blowing in direction to make it functional it was operated on the tracks between Baltimore and Ellicott's Mills.

The Russian Ambassador, Baron de Krudner came to observe the operationof the experimental car and actually handled the sail on the trip. He was presented by the President of the railroad with a model of the car. This led to an exchange of American engineers who helped construct Russia's rail system.

The demonstration of Cooper's steam locomotive set the direction for railroad operation. The Fourth Annual Report of the B and O Railroad in 1830 states:

Experience with regard to the celerity of the conveyance of passengers during the preceeding four months on the first 13 miles of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, is of the most cheerful and convincing character. The practicability of maintaining a speed of 10 miles per hour with horses has been exhibited. With proper relays,this rate of traveling may be continued through any length of railway, the ascent and descents of which shall not exceed about 30 feet per mile.

Within the last few months, the improvements to locomotive steam engines have been such as to insure their general use on all railways of suitable gradation, and where fuel is cheap." [2.]

Wood and coal would fuel the first boilers. Riding the train could be a dirty experience as smoke and cinders wreaked havoc on the wardrobes of female travelers. Clean coal was used and promoted by the New York Central in this little rhyme:

Says Phoebe Snow

about to go

upon a trip to Buffalo

"My gown stays white

from morn till night

Upon the Road of Anthracite"

The modern railroad saw the use of diesel and electric power. Welded rails and modern track alignment would finally create the illusion of a smooth and effortless glide down the tracks.

21st Century railroads would like to harness the energy of wind farms to power their catenaries [the overhead wires providing power to locomotives], but even now, as during the Nineteenth Century, the winds remain as fickle as they are romantic.

2. The early motive power of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad By Joseph Snowden Bell, p. 5.

1858 Engraving of the Thomas Viaduct on the then Baltimore and Washington Railroad, a subsidiary of the Baltimore and Ohio.

Engraving from The United States Illustrated, Charles A. Dana, Editor, c. 1858. Retrieved from Historic American Engineering Record; Library of Congress [3.]

Viaduct of the Baltimore and Washington Railroad

from The United States Illustrated, Charles A. Dana, Editor, c. 1858

The traveler may well discern in the viaduct of a railroad, a monumental atonement on the part of surveyors and engineers for the injuries their labors elsewhere inflict upon the picturesque beauty of the landscape. Who has not hailed with delight, upon many a railway, the passage over some viaduct, and welcomed it amid the journey through dust and cinders, as the pilgrim over the African desert welcomes the oasis and its well of crystal water? Underneath, tons of smoothly hewn granite press deeply into the bed of the river, a whiff of whose cooling vapor, at least, comes into the passenger’s nostrils, as he dashes over a superstructure, the length of which would have been the admiration of the Romans, whose creek like Tiber might have provoked the sneer of a “go ahead” engineer.

The “Pons Narniensis,” whose framer was the imperial Augustus; the arches of Trajan over the Danube, and the bridge of Alcántara across the Spanish Tagus, have long been famous in ancient history, whilst America, for the accommodation of no imperial cortege, but of the masses of the people, has rivalled them all in her numerous railroad viaducts, and especially in the Starrucca Viaduct upon the Erie Railroad.

The one given in the engraving was of the first built in the country, although exceeded by the one above named in length, breadth, height, and the span of the arches, it is not surpassed for beauty of location and compactness of execution. But alas, by only one or two of the thousand passengers who rush along its surface, is this beauty and compactness noticed. Now and then a passenger drops off at the neighboring station, intent upon converting his walking staff into a fishing rod, beside the shadow of its arches, or about once in a twelvemonth a detention upon the neighboring “switch” allows the traveller a saunter by its railing, or a hurried clamber down the rocky ledge which confines the waters of the Patuxent (actually the Patapsco) River and in great part forms its bed.” [4.]

This station at Fort Defiance, Virginia once served the Baltimore and Ohio's Valley Railroad.

Galaxies in Pansies

Photographs by Bob Kirchman

These close-up photographs capture the feeling of Hubble Telescope photographs from space. Photos by Bob Kirchman