Volume XIII, Issue VIII

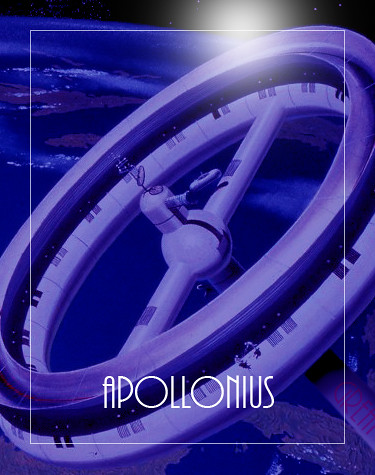

Apollonius

By Bob Kirchman

Copyright © 2017, The Kirchman Studio, all rights reserved

Chapter 2: The Great Northern

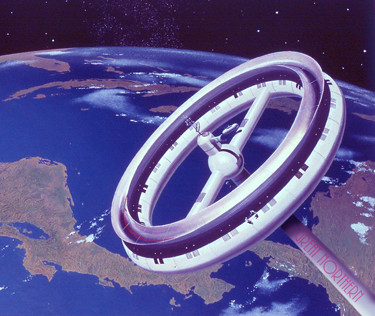

The Starship Great Northern rode in Geosynchronous Earth Orbit at Space Station/Assembly Center 005 of the Alaska Autonimous Republic. Indeed the crafty Apollonius had spun a tale of potential benefits to mankind. Also, he had invoked an odd chapter in England’s history where convicts and other undesirables were sent to colonize the remote island sub-continent of Australia and there they established a great nation. From 1788 to 1868, about 160,000 convicts were sent to penal colonies there. It was the unforeseen second chance that gave many Australians a hope and a future. Zimmerman, for his part was always willing to listen to any alternative to incarceration. His own incarceration in a U.S. Federal Prison weighed heavy upon him… that and the notion that Theodor Herzl had put forth that there could indeed be a society without prisons! Apollonius had opened his checkbook and the project had been accomplished in record time to build an interplanetary star ship. Cape Lisbon International Spaceport, for its part, provided new and unheard of economy and reliability putting men and materials in orbit. And so the ship, capable of carrying fifty souls on the nine month journey to mars orbited ‘at anchor’ at SSAC005. The ship was being stocked with 3D printers and plans for much of the space colony’s needed machinery, which would be created on the planet’s surface. The unmanned probe had already been sent and would confirm the resources were there to construct what the colonists required. The plan was to expand from the initial living pods out into a full-scale biosphere, much resembling the one on Big Diomede, to protect the colonists from the effects of Mars’s thin atmosphere which was mainly CO2. In the Zimmerman Organization offices in Wales, greenhouse designs originally created for the tundra were being reconfigured for use on Mars. The parts were also being redesigned for ‘printing’ in factories on the planet itself. Botanists were collecting and cultivating plants that would refresh the atmosphere even as they provided food for the settlers. “Eventually we’ll need to establish a colony of 40,000 people in order to allow for a healthy and diverse stock.” Apollonius had said. Still, the initial mission was defined by the limitations of budget and practicality.

The Great Northern had a forward section with a rotating centrifugal ring to create the sensation of gravity for the passengers and crew. It was compact but comfortable. Portholes in the compartments offset the claustrophobic compactness. The ship had been assembled from components destined for platform SS/AC006, the next orbital station to be built, and fitted with a fusion engine to become a large space-going vessel. The fusion engine was at the end of a long tube to the rear of the configuration and the bridge sat directly in front of the gravity ring section. At the helm was Captain Abiyah Ben Gurion, a veteran of the Israeli Air Force. A thoughtful man who spoke little, he had been at the top of his class in astronaut training and was given the opportunity to pilot the first mission to Mars. There was to be no forced assignment to this mission by Zimmerman’s decree. Even the ’settlers’ were to be volunteers. On this point he had won over Apollonius’s insistence that the crew be chosen by George himself and ordered on the mission. The result was a tight group of hard-core military personnel as crew and an odd mix of adventure seekers and condemned men and women who did not fit into society in the potential pool of settlers. Zimmerman and Apollonius would oversee the final selection. Captain Ben Gurion was typical of the crewmen, a silent loner who kept to himself but was known for his devotion to his fellow airmen. He was not unlike those seamen of old who captained oceangoing vessels under sail. His passion was music and he earned the nickname ’Nemo’ from the fact that he had a little midi keyboard in his cabin and the strains of his music often spilled out into the passageways. The crew loved it and almost never addressed him as anything but.

Nemo would be a man without a country for the duration of the two-year voyage. It would take about nine months to get there and then require about six months of orbiting the planet in a support capacity to the colony. After that, there would be the long return trip. The plan was to rotate crews each trip but Nemo secretly wished he could stay on for longer. “Not to worry,” he thought to himself. “Distinguish yourself in command and there won’t be many who seek to take it from you.”

(to be continued)

The Eclipse of 08.21.2017

The eclipse reaches totality as recorded by a NASA telescope in Madras, Oregon. NASA Image.

The International Space Station, with a crew of six onboard, is seen in silhouette as it transits the Sun at roughly five miles per second during a partial solar eclipse, Monday, Aug. 21, 2017 from Ross Lake, Northern Cascades National Park, Washington. Onboard as part of Expedition 52 are: NASA astronauts Peggy Whitson, Jack Fischer, and Randy Bresnik; Russian cosmonauts Fyodor Yurchikhin and Sergey Ryazanskiy; and ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Paolo Nespoli. A total solar eclipse swept across a narrow portion of the contiguous United States from Lincoln Beach, Oregon to Charleston, South Carolina. A partial solar eclipse was visible across the entire North American continent along with parts of South America, Africa, and Europe. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

The eclipse paints a 'pinhole camera' image through the trees in Staunton, Virginia. Photos by Bob Kirchman.

Around the World in 80 Days

By Jules Verne, Chapter VI

In which Fix, the Detective, Betrays a Very Natural Impatience

The circumstances under which this telegraphic dispatch about Phileas Fogg was sent were as follows:

The steamer Mongolia, belonging to the Peninsular and Oriental Company, built of iron, of two thousand eight hundred tons burden, and five hundred horse-power, was due at eleven o’clock a.m. on Wednesday, the 9th of October, at Suez. The Mongolia plied regularly between Brindisi and Bombay via the Suez Canal, and was one of the fastest steamers belonging to the company, always making more than ten knots an hour between Brindisi and Suez, and nine and a half between Suez and Bombay.

Two men were promenading up and down the wharves, among the crowd of natives and strangers who were sojourning at this once straggling village — now, thanks to the enterprise of M. Lesseps, a fast-growing town. One was the British consul at Suez, who, despite the prophecies of the English Government, and the unfavourable predictions of Stephenson, was in the habit of seeing, from his office window, English ships daily passing to and fro on the great canal, by which the old roundabout route from England to India by the Cape of Good Hope was abridged by at least a half. The other was a small, slight-built personage, with a nervous, intelligent face, and bright eyes peering out from under eyebrows which he was incessantly twitching. He was just now manifesting unmistakable signs of impatience, nervously pacing up and down, and unable to stand still for a moment. This was Fix, one of the detectives who had been dispatched from England in search of the bank robber; it was his task to narrowly watch every passenger who arrived at Suez, and to follow up all who seemed to be suspicious characters, or bore a resemblance to the description of the criminal, which he had received two days before from the police headquarters at London. The detective was evidently inspired by the hope of obtaining the splendid reward which would be the prize of success, and awaited with a feverish impatience, easy to understand, the arrival of the steamer Mongolia.

So you say, consul,” asked he for the twentieth time, “that this steamer is never behind time?”

No, Mr. Fix,” replied the consul. “She was bespoken yesterday at Port Said, and the rest of the way is of no account to such a craft. I repeat that the Mongolia has been in advance of the time required by the company’s regulations, and gained the prize awarded for excess of speed.”

Does she come directly from Brindisi?”

Directly from Brindisi; she takes on the Indian mails there, and she left there Saturday at five p.m. Have patience, Mr. Fix; she will not be late. But really, I don’t see how, from the description you have, you will be able to recognise your man, even if he is on board the Mongolia.”

A man rather feels the presence of these fellows, consul, than recognises them. You must have a scent for them, and a scent is like a sixth sense which combines hearing, seeing, and smelling. I’ve arrested more than one of these gentlemen in my time, and, if my thief is on board, I’ll answer for it; he’ll not slip through my fingers.”

I hope so, Mr. Fix, for it was a heavy robbery.”

A magnificent robbery, consul; fifty-five thousand pounds! We don’t often have such windfalls. Burglars are getting to be so contemptible nowadays! A fellow gets hung for a handful of shillings!”

Mr. Fix,” said the consul, “I like your way of talking, and hope you’ll succeed; but I fear you will find it far from easy. Don’t you see, the description which you have there has a singular resemblance to an honest man?”

Consul,” remarked the detective, dogmatically, “great robbers always resemble honest folks. Fellows who have rascally faces have only one course to take, and that is to remain honest; otherwise they would be arrested off-hand. The artistic thing is, to unmask honest countenances; it’s no light task, I admit, but a real art.”

Mr. Fix evidently was not wanting in a tinge of self-conceit.

Little by little the scene on the quay became more animated; sailors of various nations, merchants, ship-brokers, porters, fellahs, bustled to and fro as if the steamer were immediately expected. The weather was clear, and slightly chilly. The minarets of the town loomed above the houses in the pale rays of the sun. A jetty pier, some two thousand yards along, extended into the roadstead. A number of fishing-smacks and coasting boats, some retaining the fantastic fashion of ancient galleys, were discernible on the Red Sea.

As he passed among the busy crowd, Fix, according to habit, scrutinised the passers-by with a keen, rapid glance.

It was now half-past ten.

The steamer doesn’t come!” he exclaimed, as the port clock struck.

She can’t be far off now,” returned his companion.

How long will she stop at Suez?”

Four hours; long enough to get in her coal. It is thirteen hundred and ten miles from Suez to Aden, at the other end of the Red Sea, and she has to take in a fresh coal supply.”

And does she go from Suez directly to Bombay?”

Without putting in anywhere.”

Good!” said Fix. “If the robber is on board he will no doubt get off at Suez, so as to reach the Dutch or French colonies in Asia by some other route. He ought to know that he would not be safe an hour in India, which is English soil.”

Unless,” objected the consul, “he is exceptionally shrewd. An English criminal, you know, is always better concealed in London than anywhere else.”

This observation furnished the detective food for thought, and meanwhile the consul went away to his office. Fix, left alone, was more impatient than ever, having a presentiment that the robber was on board the Mongolia. If he had indeed left London intending to reach the New World, he would naturally take the route via India, which was less watched and more difficult to watch than that of the Atlantic. But Fix’s reflections were soon interrupted by a succession of sharp whistles, which announced the arrival of the Mongolia. The porters and fellahs rushed down the quay, and a dozen boats pushed off from the shore to go and meet the steamer. Soon her gigantic hull appeared passing along between the banks, and eleven o’clock struck as she anchored in the road. She brought an unusual number of passengers, some of whom remained on deck to scan the picturesque panorama of the town, while the greater part disembarked in the boats, and landed on the quay.

Fix took up a position, and carefully examined each face and figure which made its appearance. Presently one of the passengers, after vigorously pushing his way through the importunate crowd of porters, came up to him and politely asked if he could point out the English consulate, at the same time showing a passport which he wished to have visaed. Fix instinctively took the passport, and with a rapid glance read the description of its bearer. An involuntary motion of surprise nearly escaped him, for the description in the passport was identical with that of the bank robber which he had received from Scotland Yard.

Is this your passport?” asked he.

No, it’s my master’s.”

And your master is —”

He stayed on board.”

But he must go to the consul’s in person, so as to establish his identity.”

Oh, is that necessary?”

Quite indispensable.”

And where is the consulate?”

There, on the corner of the square,” said Fix, pointing to a house two hundred steps off.

I’ll go and fetch my master, who won’t be much pleased, however, to be disturbed.”

The passenger bowed to Fix, and returned to the steamer.

(to be continued)

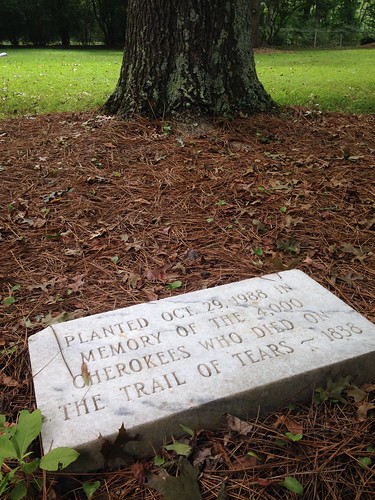

New Echota, Cherokee Nation Capital

Photos by Bob Kirchman

Many Cherokee farmers and their families were forced from small farms like this into stockades and eventually removed to Oklahoma in the 'Trail of Tears.'

It is a warm August day as I travel to Atlanta Georgia through what was once the home of a great nation. Pulling off of Interstate 75, it is a short drive to the reconstructed capital of the Cherokee, New Echota. It was never a large city but it would swell to an encampment of hundreds of people when the council was in session.

The offices of the Cherokee Nation's Phoenix, a newspaper published in both English and Cherokee.

The Phoenix printing press.

Sequoyah's 'Talking Leaves.'

The Gift of Language

How Sequoyah Gave His People Written Words

Perhaps the most remarkable man who has ever lived on Georgia soil was neither a politician, nor a soldier, nor an ecclesiastic, nor a scholar, but merely a Cherokee Indian of mixed blood. And strange to say, this Indian acquired permanent fame, neither expecting or seeking it." -- H. A. Scomp, Emory College

He was hardly someone you would predict would create such a significant contribution to his nation. George Gist was born to a Cherokee mother, Wu-teh, a member of the Paint Clan, and Nathanial Gist, an English fur trader near the village of Tushkeegee on the Tennessee River. The year was around 1760 but no one knows for sure. Learning the ways of the Cherokee, young George became a trapper and a fur trader himself. He would probably have lived out his days as a man of the forest, but he suffered a hunting accident (or possibly succumbed to a crippling disease, depending on which version of his story you read), but the young man was permanently disabled, unable to earn his living by the skills he had been taught in childhood.

George Gist developed a talent for metal working. He learned to be a blacksmith and silversmith. His disability became both a source of ridicule (Sequoyah means "pig's foot" in Cherokee) and a spur to greater things. The man was a good learner and became a competent craftsman. A man who purchased one of his pieces suggested that he sign his work, but he was unable to. He could not write! And here as well his story might have ended, but events in the greater world were to spur him to his greatest work. Sequoyah married a Cherokee woman and raised a family. They moved to Cherokee County in Georgia where George learned how to write his name from a local farmer. Later he joined other Cherokees who fought under Andrew Jackson against England in the War of 1812. Though he never learned to read or write English, Sequoyah was fascinated by the white man's ability to create "talking leaves" by making marks on paper.

As early as 1809, Sequoyah was exploring the creation of a Cherokee alphabet. Though scholars believe there may have once been a written Cherokee language that was later forgotten, there was no written Cherokee language when Sequoyah was a youth. People suspected that the white man's words "moved around on the paper," and the time was right for Cherokee to be able to read things for themselves. Cherokee soldiers could not write letters home, read military orders for themselves, or record events they wished to remember. When he returned home from the war, he worked in earnest on a phonetic alphabet of 86 letters to write the Cherokee Language. Sequoyah became something of a recluse. His friends and family ridiculed him. Some said he was insane or practicing witchcraft. Moving West to Arkansas, he continued his great work.

He found that his young daughter Ayoka could easily learn to use the syllabary and demonstrated this to his cousin, George Lowrey, who encouraged him to demonstrate the use of the syllabary to the public. In a Cherokee court case in Chattooga, he read an argument about a boundary line from a piece of paper. In 1821 the Cherokee Nation officially adopted Sequoya's alphabet and within a matter of months thousands of Cherokee learned to read and write! In 1824 the Cherokee National Council at New Echota, Georgia presented him with a silver medal. Sequoyah proudly wore it for the rest of his life. He was given a $300 annuity and his widow continued to receive it after he died.

By 1825 the Cherokee had the Bible in their own language along with hymnals and all sorts of educational materials. There was even a large group of Moravian Cherokee. Legal documents and books of every kind were available, all translated into the Cherokee Language. In 1827 The Cherokee National Council funded the printing of Tsa la gi Tsu lehesanunhi," the Cherokee Phoenix. It was the first Native American newspaper printed in the United States. It was produced in the Cherokee Capital, New Echota on a press shipped there from Boston. The paper had parallel columns in Cherokee and English, printed side by side.

Sadly, the discovery of gold in North Georgia, unscrupulous men and treachery in treaty would lead to the removal of most of the Eastern nation. Sequoyah moved to Oklahoma were he served as an envoy to Washington D.C. to assist the displaced Eastern Cherokees. He continued to serve his people as a diplomat and a statesman. Well into his eighties, he traveled West again, looking for a band of Cherokees who were said to have moved to Mexico. He took ill and died in 1843 and the location of his grave remains unknown to this day. Two species of giant redwood trees have been named in his honor, as has Sequoia National Park in California. He gave his people the gift of literacy. His contribution is unique, as he, an uneducated, seemingly undistinguished individual, created a totally new system of writing for his beloved nation.

Remembering History

After the residents of New Echota were taken away in the ‘Trail of Tears,’ the town itself disappeared. The state of Georgia had held a lottery to redistribute the land and it became farmland. The houses were taken down, save for that of Samuel Worcester, missionary to the Cherokee and Postmaster. It survived in other hands. The trees that shaded the streets were cut down. The town itself was but a memory.

In the 1960’s a group of people came together who thought it important to remember the great nation that had once occupied North Georgia. They persuaded the state of Georgia to create the present park at New Echota. The principle buildings have been reconstructed and stand in silent monument to those who were ripped from their land a century before.

Cultural Transformation

Has Isaiah 1:18 Ever Actually Happened?

By Herb Reese

[click to read]

Come now, let us settle the matter,” says the LORD. “Though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they are red as crimson, they shall be like wool.” – Isaiah 1:18

I memorized this wonderful and amazing verse as a child. At the time, I was told that it referred to my personal salvation; that when I placed my faith in Jesus Christ, God wiped all of my sin away and sees me as righteous in Christ Jesus.

Unfortunately, Isaiah 1:18 is not talking about my personal salvation – or anyone’s for that matter.

Of course, the Bible teaches in other places that at the moment of our salvation, God forgives us of all of our sin. “To the one who does not work but trusts God who justifies the ungodly, their faith is credited as righteousness,” Paul writes in Romans 4:5. But personal salvation and forgiveness is not what Isaiah 1:18 is talking about.

What Isaiah 1:18 is talking about is cultural transformation. The reason we know this is from the context. “Woe to the sinful nation!” God says to Israel in verse 4. In verse 7, God again addresses his litany to the entire nation: “Your country is desolate, your cities burned with fire.” Then He turns his anger on Israel’s political leadership: “Hear the word of the Lord, you rulers of Sodom,” (verse 10). God’s disdain for Israel even includes it’s religious leaders: “The multitude of your sacrifices, what are they to me? says the Lord. I have more than enough of burnt offerings, of rams and the fat of fattened animals” (verse 11).

In reality, what God is doing in the first sixteen verses of Isaiah 1 is making a case for judging Israel. God, as prosecutor, is about to haul the nation into court for judgement. But in verse 18, He’s saying, It’s not too late. We can settle out of court: “Come now, let us settle the matter.”

So what does God want Israel to do in order to settle out of court? In an extremely important statement that all believers need to pay very close attention to, God gives us His conditions:”Learn to do right; seek justice. Defend the oppressed. Take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow.” (read more)

Daryl Davis.

Daryl Davis's Unique Work

By Benny Johnson

[click to read]

There are many headlines in the news today about fighting white supremacy and the Ku Klux Klan with violence.

However, decades ago 58-year-old Blues musician Daryl Davis learned the most effective way to get a Klansman to give up his hood: friendship.

Daryl Davis has a unique hobby.

In his spare time, he befriends white supremacists. Lots of them. Hundreds. He goes to where they live. Meets them at their rallies. Dines with them in their homes. He gets to know them because, in his words, “How can you hate me when you don't even know me? Look at me and tell me to my face why you should lynch me.” (read more)