Volume XIII, Issue X

Apollonius

By Bob Kirchman

Copyright © 2017, The Kirchman Studio, all rights reserved

Chapter 4: Apollonius Takes Charge

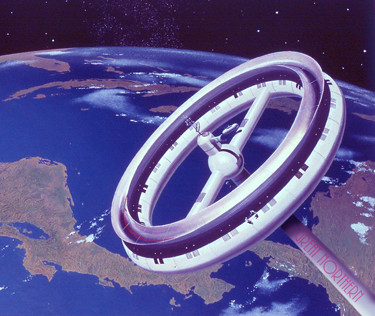

In the endless light of the midnight sun the supplying of Great Northern from linear induction shuttles proceeded round the clock. Soon the voyage would begin. Cohen and Ben Gurion shuttled down to meet with Zimmerman. A plan was laid out for command of the Great Northern and oversight of the colonists on board. Once shuttled to the Martian surface, the colony would be administered by the Alaska Autonimous Republic and Israel, but there would be no official presence of either nation there. Because AAR/Israel operated the only ship capable of supplying the colony, this would be enforceable from Earth. Should the colony divert from the agreed upon mission and somehow challenge this chain of command, supply by Great Northern could be suspended. If, as Apollonius had hinted, there were great resources to be found beneath the planet’s surface, the mining off them might finance additional long-distance ships and allow for annual and then twice-yearly visits and departures. George Apollonius might have detested the added oversight over the mission but he was gracious as he nodded to it. Soon the craft would be underway and he would be pretty much in charge of everything anyway. The crew would be busied by the operation of the ship and the colonists would be under his leadership as they traveled outward. Finally, Apollonius came aboard on the last Earth shuttle. He and 29 colonists made up the passenger manifest as the Zimmerman Organization had exercised no hesitation in disqualifying those it felt it needed to. That number could be shuttled down to the Martian surface in the ten Mars shuttles she carried. These craft would remain on the planet. Should an emergency force evacuation of the planet, all the colonists could take off in these craft and with emergency rationing in place, make it back to Earth orbit if need be. Future missions would add more ‘lifeboat’ craft to the colony.

George Apollonius took up residence in the VIP suite, the only quarters that came close to being spacious on the craft. The other 29 colonists were still crowded, though there were empty bunks. The chief surgeon and the engineers for the colony had slightly larger quarters but the cramped nature of the compartments brought to mind ocean voyages in sailing ships. The nine crewmen who would remain on Great Northern had slightly larger cabins than the higher ranking colonists. Due to the staggering of hours on duty, each crew member occupied a single cabin but because all but one were married, the couples enjoyed the luxury of a two-room suite apiece. There were ten crew cabins and a wardroom where the crew would take their meals, watch movies, read and enjoy large-screen Skype conversation with family and friends on Earth. Exercise could be had on some equipment there as well and all of the crew used the gravity ring as a sort of perpetual track for running. Apollonius rarely left his cabin. He was the oldest person on board but the colonists knew that he would be governor of the new settlement and pretty much deferred to his commands.

The settlers were a rather raggedy lot, some prisoners taking up the offer of land and a future in a new world, some were adventure seekers who possessed skills needed for the venture. Others seemed to be of a quiet mysterious sort. They had skills, of course, but they seemed to fit some profile set by Apollonius himself. The selection process in the end rather resembled final jury selection for a drug trial. Zimmerman and Apollonius faced off like prosecution attorney and defense attorney and took turns questioning the final pool of applicants. Elizabeth O’Malley and Hannah were always at Rupert’s side. He requested that, knowing that in the combined pool of their insight he probably would have not agreed so readily to the mission in the first place. In the name of ‘diversity’ or in claims of potential ineptitude, team Zimmerman was able to reduce substantially the number of people suspected of being Apollonius stooges. Still, in the end there was a small group that they noted Cohen and Ben Gurion should watch closely. Twenty-nine men and women and Apollonius would initially man the Mars station. Though they could have sent fifty cramped in the initial voyage, it was remembered that the Great Lake freighters could be operated quite smoothly with a crew of thirty or less. Crewmen would perform varied functions as needed and could be trained to do other functions en route. When cabin fever rose to a head, a crew this size could blow off steam with a few fights and life would settle down again. Full-blown mutiny was unlikely.

Zimmerman and Ben Gurion did not fail to consider the possibility, however, that Apollonius might have some reason in his mind to take over the ship. He was a smooth persuader as he had been on Earth, using his fortune to influence the leadership of the world. It was clear to everyone that this was ‘his’ colony on Mars. The Federalism of AAR and Israel would not quibble with that. All of the colonists were duly warned/informed of this. Apollonius’s Billions were funding the venture so essentially the creepy old billionaire was ‘buying’ the first house on Mars. The Zimmermans doubted it would ever become a colony of 40,000 souls, however, and Cohen and Ben Gurion would still have the honor of first setting foot on the Martian surface. They would lay no claim, rather the colony would be like the bases of exploration in Antarctica… operated by their respective countries but on soil that was considered open to all mankind. Research would be done, resources would be sought. It was like the beginning of a new Century of exploration but the reality was that Sixteenth Century explorers had found ready access to the new world’s treasure. Mars would not likely offer such opportunities. Cohen and Ben Gurion, once they had established that it was safe, would return to Great Northern and the colonists themselves, who would train en route, would monitor their one-way descent to the ‘new colony.’

Abiyah told Sarah that she should go down the ladder first and be like Neil Armstrong in the history books. “It’s not likely you’ll meet a bear or anything down there, and you’ll have one whale of a story to tell the grandkids someday!”

You are too modest, Abiyah!” She responded, recounting many of the heroic man’s past achievements and victories.

Yes, but in the realm of great exploits,” Ben Gurion continued, “You need to catch up with me.”

Alright then, we’ll jump down together.” Sarah said dreamily. “That would be so romantic. History would say we touched a new world together, husband and wife!”

If I don’t push you first!”

(to be continued)

Around the World in 80 Days

By Jules Verne, Chapter IX

In which the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean Prove Propitious to the Designs of Phileas Fogg

The distance between Suez and Aden is precisely thirteen hundred and ten miles, and the regulations of the company allow the steamers one hundred and thirty-eight hours in which to traverse it. The Mongolia, thanks to the vigorous exertions of the engineer, seemed likely, so rapid was her speed, to reach her destination considerably within that time. The greater part of the passengers from Brindisi were bound for India some for Bombay, others for Calcutta by way of Bombay, the nearest route thither, now that a railway crosses the Indian peninsula. Among the passengers was a number of officials and military officers of various grades, the latter being either attached to the regular British forces or commanding the Sepoy troops, and receiving high salaries ever since the central government has assumed the powers of the East India Company: for the sub-lieutenants get 280 pounds, brigadiers, 2,400 pounds, and generals of divisions, 4,000 pounds. What with the military men, a number of rich young Englishmen on their travels, and the hospitable efforts of the purser, the time passed quickly on the Mongolia. The best of fare was spread upon the cabin tables at breakfast, lunch, dinner, and the eight o’clock supper, and the ladies scrupulously changed their toilets twice a day; and the hours were whirled away, when the sea was tranquil, with music, dancing, and games.

But the Red Sea is full of caprice, and often boisterous, like most long and narrow gulfs. When the wind came from the African or Asian coast the Mongolia, with her long hull, rolled fearfully. Then the ladies speedily disappeared below; the pianos were silent; singing and dancing suddenly ceased. Yet the good ship ploughed straight on, unretarded by wind or wave, towards the straits of Bab-el-Mandeb. What was Phileas Fogg doing all this time? It might be thought that, in his anxiety, he would be constantly watching the changes of the wind, the disorderly raging of the billows — every chance, in short, which might force the Mongolia to slacken her speed, and thus interrupt his journey. But, if he thought of these possibilities, he did not betray the fact by any outward sign.

Always the same impassible member of the Reform Club, whom no incident could surprise, as unvarying as the ship’s chronometers, and seldom having the curiosity even to go upon the deck, he passed through the memorable scenes of the Red Sea with cold indifference; did not care to recognise the historic towns and villages which, along its borders, raised their picturesque outlines against the sky; and betrayed no fear of the dangers of the Arabic Gulf, which the old historians always spoke of with horror, and upon which the ancient navigators never ventured without propitiating the gods by ample sacrifices. How did this eccentric personage pass his time on the Mongolia? He made his four hearty meals every day, regardless of the most persistent rolling and pitching on the part of the steamer; and he played whist indefatigably, for he had found partners as enthusiastic in the game as himself. A tax-collector, on the way to his post at Goa; the Rev. Decimus Smith, returning to his parish at Bombay; and a brigadier-general of the English army, who was about to rejoin his brigade at Benares, made up the party, and, with Mr. Fogg, played whist by the hour together in absorbing silence.

As for Passepartout, he, too, had escaped sea-sickness, and took his meals conscientiously in the forward cabin. He rather enjoyed the voyage, for he was well fed and well lodged, took a great interest in the scenes through which they were passing, and consoled himself with the delusion that his master’s whim would end at Bombay. He was pleased, on the day after leaving Suez, to find on deck the obliging person with whom he had walked and chatted on the quays.

If I am not mistaken,” said he, approaching this person, with his most amiable smile, “you are the gentleman who so kindly volunteered to guide me at Suez?”

Ah! I quite recognise you. You are the servant of the strange Englishman —”

Just so, monsieur —”

Fix.”

Monsieur Fix,” resumed Passepartout, “I’m charmed to find you on board. Where are you bound?”

Like you, to Bombay.”

That’s capital! Have you made this trip before?”

Several times. I am one of the agents of the Peninsular Company.”

Then you know India?”

Why yes,” replied Fix, who spoke cautiously.

A curious place, this India?”

Oh, very curious. Mosques, minarets, temples, fakirs, pagodas, tigers, snakes, elephants! I hope you will have ample time to see the sights.”

I hope so, Monsieur Fix. You see, a man of sound sense ought not to spend his life jumping from a steamer upon a railway train, and from a railway train upon a steamer again, pretending to make the tour of the world in eighty days! No; all these gymnastics, you may be sure, will cease at Bombay.”

And Mr. Fogg is getting on well?” asked Fix, in the most natural tone in the world.

Quite well, and I too. I eat like a famished ogre; it’s the sea air.”

But I never see your master on deck.”

Never; he hasn’t the least curiosity.”

Do you know, Mr. Passepartout, that this pretended tour in eighty days may conceal some secret errand — perhaps a diplomatic mission?”

Faith, Monsieur Fix, I assure you I know nothing about it, nor would I give half a crown to find out.”

After this meeting, Passepartout and Fix got into the habit of chatting together, the latter making it a point to gain the worthy man’s confidence. He frequently offered him a glass of whiskey or pale ale in the steamer bar-room, which Passepartout never failed to accept with graceful alacrity, mentally pronouncing Fix the best of good fellows.

Meanwhile the Mongolia was pushing forward rapidly; on the 13th, Mocha, surrounded by its ruined walls whereon date-trees were growing, was sighted, and on the mountains beyond were espied vast coffee-fields. Passepartout was ravished to behold this celebrated place, and thought that, with its circular walls and dismantled fort, it looked like an immense coffee-cup and saucer. The following night they passed through the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb, which means in Arabic The Bridge of Tears, and the next day they put in at Steamer Point, north-west of Aden harbour, to take in coal. This matter of fuelling steamers is a serious one at such distances from the coal-mines; it costs the Peninsular Company some eight hundred thousand pounds a year. In these distant seas, coal is worth three or four pounds sterling a ton.

The Mongolia had still sixteen hundred and fifty miles to traverse before reaching Bombay, and was obliged to remain four hours at Steamer Point to coal up. But this delay, as it was foreseen, did not affect Phileas Fogg’s programme; besides, the Mongolia, instead of reaching Aden on the morning of the 15th, when she was due, arrived there on the evening of the 14th, a gain of fifteen hours.

Mr. Fogg and his servant went ashore at Aden to have the passport again visaed; Fix, unobserved, followed them. The visa procured, Mr. Fogg returned on board to resume his former habits; while Passepartout, according to custom, sauntered about among the mixed population of Somanlis, Banyans, Parsees, Jews, Arabs, and Europeans who comprise the twenty-five thousand inhabitants of Aden. He gazed with wonder upon the fortifications which make this place the Gibraltar of the Indian Ocean, and the vast cisterns where the English engineers were still at work, two thousand years after the engineers of Solomon.

Very curious, very curious,” said Passepartout to himself, on returning to the steamer. “I see that it is by no means useless to travel, if a man wants to see something new.” At six p.m. the Mongolia slowly moved out of the roadstead, and was soon once more on the Indian Ocean. She had a hundred and sixty-eight hours in which to reach Bombay, and the sea was favourable, the wind being in the north-west, and all sails aiding the engine. The steamer rolled but little, the ladies, in fresh toilets, reappeared on deck, and the singing and dancing were resumed. The trip was being accomplished most successfully, and Passepartout was enchanted with the congenial companion which chance had secured him in the person of the delightful Fix. On Sunday, October 20th, towards noon, they came in sight of the Indian coast: two hours later the pilot came on board. A range of hills lay against the sky in the horizon, and soon the rows of palms which adorn Bombay came distinctly into view. The steamer entered the road formed by the islands in the bay, and at half-past four she hauled up at the quays of Bombay.

Phileas Fogg was in the act of finishing the thirty-third rubber of the voyage, and his partner and himself having, by a bold stroke, captured all thirteen of the tricks, concluded this fine campaign with a brilliant victory.

The Mongolia was due at Bombay on the 22nd; she arrived on the 20th. This was a gain to Phileas Fogg of two days since his departure from London, and he calmly entered the fact in the itinerary, in the column of gains.

(to be continued)

Bejeweled Clover. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Around the World in 80 Days

By Jules Verne, Chapter X

In which Passepartout is Only Too Glad to Get off with the Loss of His Shoes

Everybody knows that the great reversed triangle of land, with its base in the north and its apex in the south, which is called India, embraces fourteen hundred thousand square miles, upon which is spread unequally a population of one hundred and eighty millions of souls. The British Crown exercises a real and despotic dominion over the larger portion of this vast country, and has a governor-general stationed at Calcutta, governors at Madras, Bombay, and in Bengal, and a lieutenant-governor at Agra.

But British India, properly so called, only embraces seven hundred thousand square miles, and a population of from one hundred to one hundred and ten millions of inhabitants. A considerable portion of India is still free from British authority; and there are certain ferocious rajahs in the interior who are absolutely independent. The celebrated East India Company was all-powerful from 1756, when the English first gained a foothold on the spot where now stands the city of Madras, down to the time of the great Sepoy insurrection. It gradually annexed province after province, purchasing them of the native chiefs, whom it seldom paid, and appointed the governor-general and his subordinates, civil and military. But the East India Company has now passed away, leaving the British possessions in India directly under the control of the Crown. The aspect of the country, as well as the manners and distinctions of race, is daily changing.

Formerly one was obliged to travel in India by the old cumbrous methods of going on foot or on horseback, in palanquins or unwieldly coaches; now fast steamboats ply on the Indus and the Ganges, and a great railway, with branch lines joining the main line at many points on its route, traverses the peninsula from Bombay to Calcutta in three days. This railway does not run in a direct line across India. The distance between Bombay and Calcutta, as the bird flies, is only from one thousand to eleven hundred miles; but the deflections of the road increase this distance by more than a third.

The general route of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway is as follows: Leaving Bombay, it passes through Salcette, crossing to the continent opposite Tannah, goes over the chain of the Western Ghauts, runs thence north-east as far as Burhampoor, skirts the nearly independent territory of Bundelcund, ascends to Allahabad, turns thence eastwardly, meeting the Ganges at Benares, then departs from the river a little, and, descending south-eastward by Burdivan and the French town of Chandernagor, has its terminus at Calcutta.

The passengers of the Mongolia went ashore at half-past four p.m.; at exactly eight the train would start for Calcutta.

Mr. Fogg, after bidding good-bye to his whist partners, left the steamer, gave his servant several errands to do, urged it upon him to be at the station promptly at eight, and, with his regular step, which beat to the second, like an astronomical clock, directed his steps to the passport office. As for the wonders of Bombay its famous city hall, its splendid library, its forts and docks, its bazaars, mosques, synagogues, its Armenian churches, and the noble pagoda on Malabar Hill, with its two polygonal towers — he cared not a straw to see them. He would not deign to examine even the masterpieces of Elephanta, or the mysterious hypogea, concealed south-east from the docks, or those fine remains of Buddhist architecture, the Kanherian grottoes of the island of Salcette.

Having transacted his business at the passport office, Phileas Fogg repaired quietly to the railway station, where he ordered dinner. Among the dishes served up to him, the landlord especially recommended a certain giblet of “native rabbit,” on which he prided himself.

Mr. Fogg accordingly tasted the dish, but, despite its spiced sauce, found it far from palatable. He rang for the landlord, and, on his appearance, said, fixing his clear eyes upon him, “Is this rabbit, sir?”

Yes, my lord,” the rogue boldly replied, “rabbit from the jungles.”

And this rabbit did not mew when he was killed?”

Mew, my lord! What, a rabbit mew! I swear to you —”

Be so good, landlord, as not to swear, but remember this: cats were formerly considered, in India, as sacred animals. That was a good time.”

For the cats, my lord?”

Perhaps for the travellers as well!”

After which Mr. Fogg quietly continued his dinner. Fix had gone on shore shortly after Mr. Fogg, and his first destination was the headquarters of the Bombay police. He made himself known as a London detective, told his business at Bombay, and the position of affairs relative to the supposed robber, and nervously asked if a warrant had arrived from London. It had not reached the office; indeed, there had not yet been time for it to arrive. Fix was sorely disappointed, and tried to obtain an order of arrest from the director of the Bombay police. This the director refused, as the matter concerned the London office, which alone could legally deliver the warrant. Fix did not insist, and was fain to resign himself to await the arrival of the important document; but he was determined not to lose sight of the mysterious rogue as long as he stayed in Bombay. He did not doubt for a moment, any more than Passepartout, that Phileas Fogg would remain there, at least until it was time for the warrant to arrive.

Passepartout, however, had no sooner heard his master’s orders on leaving the Mongolia than he saw at once that they were to leave Bombay as they had done Suez and Paris, and that the journey would be extended at least as far as Calcutta, and perhaps beyond that place. He began to ask himself if this bet that Mr. Fogg talked about was not really in good earnest, and whether his fate was not in truth forcing him, despite his love of repose, around the world in eighty days!

Having purchased the usual quota of shirts and shoes, he took a leisurely promenade about the streets, where crowds of people of many nationalities — Europeans, Persians with pointed caps, Banyas with round turbans, Sindes with square bonnets, Parsees with black mitres, and long-robed Armenians — were collected. It happened to be the day of a Parsee festival. These descendants of the sect of Zoroaster — the most thrifty, civilised, intelligent, and austere of the East Indians, among whom are counted the richest native merchants of Bombay — were celebrating a sort of religious carnival, with processions and shows, in the midst of which Indian dancing-girls, clothed in rose-coloured gauze, looped up with gold and silver, danced airily, but with perfect modesty, to the sound of viols and the clanging of tambourines. It is needless to say that Passepartout watched these curious ceremonies with staring eyes and gaping mouth, and that his countenance was that of the greenest booby imaginable.

Unhappily for his master, as well as himself, his curiosity drew him unconsciously farther off than he intended to go. At last, having seen the Parsee carnival wind away in the distance, he was turning his steps towards the station, when he happened to espy the splendid pagoda on Malabar Hill, and was seized with an irresistible desire to see its interior. He was quite ignorant that it is forbidden to Christians to enter certain Indian temples, and that even the faithful must not go in without first leaving their shoes outside the door. It may be said here that the wise policy of the British Government severely punishes a disregard of the practices of the native religions.

Passepartout, however, thinking no harm, went in like a simple tourist, and was soon lost in admiration of the splendid Brahmin ornamentation which everywhere met his eyes, when of a sudden he found himself sprawling on the sacred flagging. He looked up to behold three enraged priests, who forthwith fell upon him; tore off his shoes, and began to beat him with loud, savage exclamations. The agile Frenchman was soon upon his feet again, and lost no time in knocking down two of his long-gowned adversaries with his fists and a vigorous application of his toes; then, rushing out of the pagoda as fast as his legs could carry him, he soon escaped the third priest by mingling with the crowd in the streets.

At five minutes before eight, Passepartout, hatless, shoeless, and having in the squabble lost his package of shirts and shoes, rushed breathlessly into the station.

Fix, who had followed Mr. Fogg to the station, and saw that he was really going to leave Bombay, was there, upon the platform. He had resolved to follow the supposed robber to Calcutta, and farther, if necessary. Passepartout did not observe the detective, who stood in an obscure corner; but Fix heard him relate his adventures in a few words to Mr. Fogg.

I hope that this will not happen again,” said Phileas Fogg coldly, as he got into the train. Poor Passepartout, quite crestfallen, followed his master without a word. Fix was on the point of entering another carriage, when an idea struck him which induced him to alter his plan.

No, I’ll stay,” muttered he. “An offence has been committed on Indian soil. I’ve got my man.”

Just then the locomotive gave a sharp screech, and the train passed out into the darkness of the night.

(to be continued)

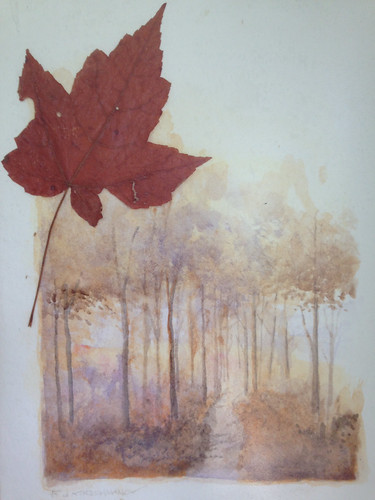

Forest, New Echota

Although the area surrounding New Echota, the Cherokee Capital, was cleared for farmland after the Cherokee Removal, the forest has returned.

Photo by Bob Kirchman.

New Echota Houses of Government

Reconstructed Supreme Courthouse. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

In 1825 New Echota was officially designated as the Cherokee Capital. The Council had been meeting in New Town (as New Echota was originally known), on the headwaters of the Oostanaula River, since 1819 and the Council house was built in 1822. Beginning in 1823, the Cherokee Supreme Court met annually to hear cases appealed from lower district courts. The Supreme Courthouse was constructed in 1829.

The government was set up similar to that of the United States, with a Legislative, Judicial and Executive Branch. The Council chose the Executive Branch officers, the Principle Chief, the Vice-Principal chief and the Treasurer.

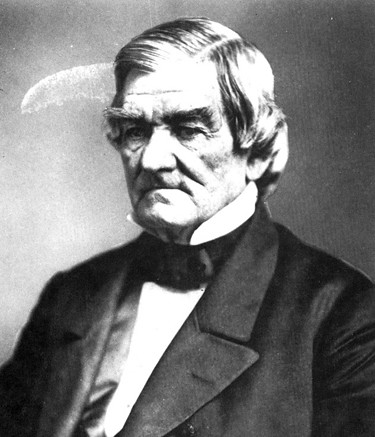

Principal Chief John Ross, who's Cherokee name was Tsan-Usdi, and is also known as Koo-wi-s-gu-wi, the name of a mythological, or rare migratory bird; served in that capacity from 1828 to 1866. He led his people through the times of the Cherokee Removal and the Civil War. Although he was only 1/8 Cherokee, the son of a Scotch Father and a Cherokee mother, he was raised traditionally. The full-blooded Cherokee recognized his skills in dealing with the United States government and the settlers around them who wanted their land. He was a tireless advocate for his people, resisting the removal. His wife Quatie, mother of their five children, died on the ‘Trail of Tears.’

Council House. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Principal Chief John Ross. Archives of the State of Georgia

Cherokee Portal

Painting by Bob Kirchman

Cherokee Portal. Bob Kirchman 1998.

I painted this little watercolor nineteen years ago when I went to another conference in Georgia. On that trip I was able to go off in the mountains and had time to paint. It was a rainy day and I felt in the soft subdued light and mist like I had been transported to another time.

Stone Mountain, near present day Atlanta, was sacred to the Cherokees and the Creeks and the two nations used it as a meeting place.

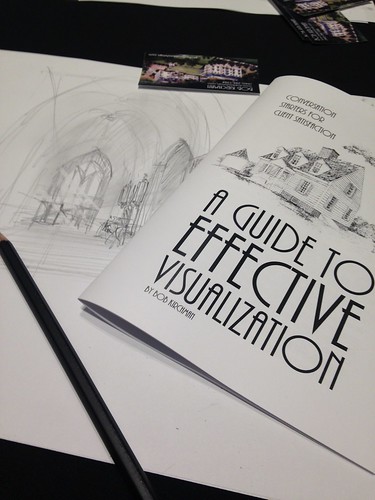

Note from Atlanta Workshop

We received this note from a participant in the AIBD Conference:

Thank you so much, Bob! Your work is amazing and the workshop gave me much better confidence in my ability to sketch my ideas for a client. I've been doing this a long time so you wouldn't think there would be a lack of confidence, but.... so it goes.” – JH

AIBD Photo.

Workshop Materials. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Bustling Atlanta. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Flooded Houston. Samaritan's Purse Photo.

Texas Needs Us

What is Helpful and What is Not

The devastation in Houston and Victoria Texas is still fresh in our memories. Samaritan’s Purse [1.] and Franklin Graham are already there, setting up bases to respond to the immediate crisis. They are well prepared to offer comfort and counseling and practical help but they will need volunteers, lots of them, as well as resources to go the distance in providing help over the months to come.

Restoring Texas will take a combined effort. Everyone from grocery chain H-E-B, Samaritan’s Purse, Southern Baptist Disaster Relief, Salvation Army and thousands of local churches and charities will roll up their sleeves and work together. In the Valley of Virginia, the birthplace of Sam Houston, God’s Pit Crew [2.] is collecting needed supplies to fill relief trailers. Not all of us can go rip out contaminated drywall but all of us can do something. That is the greatness of America.

Let us not become weary in well-doing.” But let us avoid wasted energy. We may not like Joel Osteen, but we need to get all the facts before we spend a lot of time criticizing him for not opening his church buildings to flood victims. [3.] Let’s concentrate on helping the ministries that are helping and let the others answer to God. Wait a bit before throwing out those bits of ‘news’ that don’t really serve anyone. The American Red Cross may not be the most efficient way to help anymore either, but do your own due diligence with flood charities. Erick Erickson is right to question how much of your Red Cross donation gets to the relief work, based on statistics, but he's out of line when he criticizes good ministries that have simply disagreed with him politically in the past. [4.] The truth is it will take all of us together to make a difference. [5.]

Samaritan’s Purse, Southern Baptist Disaster Relief and Salvation Army [click to visit] are among the best, but your church probably is responding too. Those we seek to help are fellow souls. Avoid the ‘Gloom and Doom’ judgment crowd. “The people of Houston right now don't need claims that the Lord has wreaked havoc on the city because sinners do what sinners do. They need to see the Lord's will and redemptive nature… God is still merciful and works to redeem.” – Jennifer LeClaire. It was not that long ago that Camille ravaged Central Virginia. As Katrina destroyed the Gulf Coast, it was compared to Camille.

My point is that we’ve been here before and we are at our best when we help our brothers and sisters. We’re all sinners, but we need to focus on the miracle of our redemption. If we truly believe the Gospel, we truly will appreciate the mercy of God.

And out of that gratitude, for the kindness of the divine in our own lives, our response should begin.

Butterfly Bush

Photos by Bob Kirchman

Dying Far From Home

One missionary I correspond with occasionally has found a unique place of outreach. Every Summer, hundreds of young college age people come to Ocean City, Maryland from Slovakia and other European nations to work in the hospitality industry there and sharpen their English. It is an exciting adventure for them.

Last Wednesday, a young woman from Slovakia, a friend of this missionary, was struck by a car as she rode her bicycle in Ocean City. Her boyfriend was with her. She was transported to the hospital in Salisbury, Maryland unconscious. She never woke up.

Her mother and her childhood pastor arrived from Slovakia and they made the decision to donate her organs. Now they are left grieving.

My own children indulged a passion for travel, engaging in such projects as working in a youth hostel in Amsterdam, teaching English in Korea, exploring New Zealand by car, building a basketball court in Thailand and going to a concert in Manchester Arena. We let our children fly, but pray as they fly beyond our familiar world. There is danger out there.

For this young woman’s family, the danger became all too real. I’m glad my friend and his wife are there to give comfort. I pray for their comfort and healing. I grieve for a family I’ve never met because I too have released that which is most precious to me to the four winds.