Volume XIII, Issue XVIII

Apollonius

By Bob Kirchman

Copyright © 2017, The Kirchman Studio, all rights reserved

Chapter 13: The Long Road Home

A new crater now scarred the Martian surface. The colony was gone! In the shadow of some rock formations there remained some greenhouses and solar panels but it was clear that the missile intended for Great Northern had fallen and detonated so as to kill the colonists instead. Sarah wiped her eyes frequently as she manned scanning equipment. “Had ANYONE survived?” she wondered. But if they did, what would become of them. All of the landing craft appeared to have been destroyed along with the colony and as this was a contingency unforeseen, there was no landing craft left with the Great Northern capable of going to the planet’s surface and returning. If indeed anyone had survived the blast they would be marooned. It would be two years before Great Northern could return and if a smaller craft were readied it would probably take six months to do so. Sarah anxiously scanned the surface each time the ship orbited above. Nothing! No sign of life appeared. No radio call for help ever came. The radiation readings from the planet suggested there would be little chance of survival anyway. Finally, with great regret, Ben-Gurion gave orders to burn the main engine and insert Great Northern into Earth Return Trajectory. It was a lonely feeling as the craft slowly gained escape momentum. Sarah was reminded of a similar moment portrayed in the movie version of an old James Michener novel where an apocryphal Apollo 18’s lunar lander crashed into the lunar surface and the command module pilot returned to Earth alone as James Taylor’s “Sweet Baby James” played as background music. In reality the lunar program had ended with Apollo 17 and LEM pilot Gene Cernan, aware of the risky nature of this craft, uttered the last words spoken from the surface of the moon: “Let’s get this mother out of here.”

If the truth be known, Abiyah Ben-Gurian must have said something similar as he eased the starship out of orbit. Only his wife knows what he said though. In communication with Earth he was cool and emotionless… but his eyes flowed with the emotion his voice covered. Sarah and Abiyah could read each other’s subtle voice inflections and facial expressions. They mourned together unashamedly.

Although their communications with Earth were crisp and professional, life aboard Great Northern eased into a relaxed sort of waiting. Sarah’s female colleagues surprised her with a baby shower and their inventiveness in creating infant clothing and toys from space supplies knew no boundaries. The good doctor moved out of the crew quarters so a nursery would be created. All would be found out upon return docking anyway so the sparse cabin became a study in pink and blue. Major Johnson even painted a little mural of children running and doing cartwheels under an apple tree as birds flew overhead. The good doctor started experimenting with a concoction of a sort of formula made from space foods should it become necessary. The due date approached as the ship traveled along the free return trajectory. Abiyah and Sarah actually enjoyed the suspense of not knowing the gender of their baby. Then one day Sarah, after a long and difficult labor, laid eyes on her son! The boy was a good nurser and the formula concoction was not needed. The two decisive pilots had discussed names, but now they gave themselves the luxury of time in deciding what to call him. Abiyah even jokingly assigned him a number but his wife ended that with one look. Now the crew flowed in the sequence of tasks necessary to begin braking into the same orbit they had left from. ‘Katherine,” their faithful trajectory computer whirred and spit out instructions to the retro engines. Soon the great mission to Mars would be over. Debriefing was planned to take place at Cape Lisbon and extended debriefing would occur at the town of Shalom inside the biosphere complex at Big Diomede. This would provide the astronauts with some privacy as they tried to make the transition back to Earth life. No doubt, there would be ticker tape parades and tours to be done but that could wait. A fairly curt press release would suffice for now.

After Apollo 11 returned from the moon, the press became bored with space exploration and did not even bother to cover the shuttle missions. They remained in this frame of mind until two shuttles were destroyed in terrible accidents and then they pretty much lobbied the shuttle program out of existence. Cape Lisbon’s linear induction launcher marked the true beginning of regular and safe transfer to orbit even though its Northern location meant that the heavy unmanned payloads and parts of space stations were still delivered by large boosters from launch sites closer to the Equator. Being sequestered on Big Diomede would give the astronauts time to think. Book contacts were already put forth and the crew would be hard at work for the next year to meet them. Sarah wondered to herself about the change. Abiyah would not take well to retirement. She was now taking on motherhood with the same energy she had poured into her work as a pilot and astronaut. What bothered her was the probability that once they stepped out of the biosphere they would be living in a fishbowl.

The Lindberghs could travel in the end and get away from it all for at least a while. Anne was able to raise five children. I just don’t see how though.” Sarah opined.

Ben Gurion thought for a minute: “The only thing left for us really is to somehow find a way to quietly pass along the things we’ve learned. Please note my emphasis on QUIETLY, if you will dearest.”

I sure don’t want to end up in some walled compound full of diplomats!” Sarah answered. “I do think there is a place where we might be useful, but not on public display.”

Sarah was ambivalent, however, about the possibility of assignment to Cape Lisbon, though that was certainly isolated. She had a child now and that changed her desires as to where she would live. Childless, she would probably not have thought twice about herself and her husband joining the ‘Baltimore Gun Club,’[1.] as the linear induction launch team called themselves. This was not a reference to their love of outdoor sports. The name came from Jules Verne’s novel ‘From the Earth to the Moon’[2.] [3.] and it referred to the munitions experts who built the large cannon from which Verne’s fictional spacecraft was launched. The Cape Lisbon team lived in a fairly austere environment. “No place to raise a child,” she mused to herself.

Between the little college with the community church and parsonage and the Zimmerman family compound there were some as yet unoccupied faculty houses for the college. Here the astronauts were to finalize their debriefing and writing. Ben-Gurion and his wife were given the one closest to the college where they would have access to people and resources as they finished their work. Sarah carried her infant son into the garden to calm his crying one afternoon. She was at first startled when a lady filling her hummingbird feeder with clear nectar looked up and saw her from the adjoining yard. “May I try holding the little fellow?” the neighbor asked… “Oh, please excuse the paint on my hands… I assure you it is dry and nursery-safe non-toxic. Mural painting today, if you must know”

And so, the copilot of the Great Northern happily surveyed a little place with very down to earth beauty and simplicity and thought: “I think I might just like it here.”

(to be continued)

Around the World in 80 Days

By Jules Verne, Chapter XXX

In which Phileas Fogg Simply Does His Duty

Three passengers including Passepartout had disappeared. Had they been killed in the struggle? Were they taken prisoners by the Sioux? It was impossible to tell.

There were many wounded, but none mortally. Colonel Proctor was one of the most seriously hurt; he had fought bravely, and a ball had entered his groin. He was carried into the station with the other wounded passengers, to receive such attention as could be of avail.

Aouda was safe; and Phileas Fogg, who had been in the thickest of the fight, had not received a scratch. Fix was slightly wounded in the arm. But Passepartout was not to be found, and tears coursed down Aouda’s cheeks.

All the passengers had got out of the train, the wheels of which were stained with blood. From the tyres and spokes hung ragged pieces of flesh. As far as the eye could reach on the white plain behind, red trails were visible. The last Sioux were disappearing in the south, along the banks of Republican River.

Mr. Fogg, with folded arms, remained motionless. He had a serious decision to make. Aouda, standing near him, looked at him without speaking, and he understood her look. If his servant was a prisoner, ought he not to risk everything to rescue him from the Indians? “I will find him, living or dead,” said he quietly to Aouda.

Ah, Mr. — Mr. Fogg!” cried she, clasping his hands and covering them with tears.

Living,” added Mr. Fogg, “if we do not lose a moment.”

Phileas Fogg, by this resolution, inevitably sacrificed himself; he pronounced his own doom. The delay of a single day would make him lose the steamer at New York, and his bet would be certainly lost. But as he thought, “It is my duty,” he did not hesitate.

The commanding officer of Fort Kearney was there. A hundred of his soldiers had placed themselves in a position to defend the station, should the Sioux attack it.

Sir,” said Mr. Fogg to the captain, “three passengers have disappeared.”

Dead?” asked the captain.

Dead or prisoners; that is the uncertainty which must be solved. Do you propose to pursue the Sioux?”

That’s a serious thing to do, sir,” returned the captain. “These Indians may retreat beyond the Arkansas, and I cannot leave the fort unprotected.”

The lives of three men are in question, sir,” said Phileas Fogg.

Doubtless; but can I risk the lives of fifty men to save three?”

I don’t know whether you can, sir; but you ought to do so.”

Nobody here,” returned the other, “has a right to teach me my duty.”

Very well,” said Mr. Fogg, coldly. “I will go alone.”

You, sir!” cried Fix, coming up; “you go alone in pursuit of the Indians?”

Would you have me leave this poor fellow to perish — him to whom every one present owes his life? I shall go.”

No, sir, you shall not go alone,” cried the captain, touched in spite of himself. “No! you are a brave man. Thirty volunteers!” he added, turning to the soldiers.

The whole company started forward at once. The captain had only to pick his men. Thirty were chosen, and an old sergeant placed at their head.

Thanks, captain,” said Mr. Fogg.

Will you let me go with you?” asked Fix.

Do as you please, sir. But if you wish to do me a favour, you will remain with Aouda. In case anything should happen to me —”

A sudden pallor overspread the detective’s face. Separate himself from the man whom he had so persistently followed step by step! Leave him to wander about in this desert! Fix gazed attentively at Mr. Fogg, and, despite his suspicions and of the struggle which was going on within him, he lowered his eyes before that calm and frank look.

I will stay,” said he.

A few moments after, Mr. Fogg pressed the young woman’s hand, and, having confided to her his precious carpet-bag, went off with the sergeant and his little squad. But, before going, he had said to the soldiers, “My friends, I will divide five thousand dollars among you, if we save the prisoners.”

It was then a little past noon.

Aouda retired to a waiting-room, and there she waited alone, thinking of the simple and noble generosity, the tranquil courage of Phileas Fogg. He had sacrificed his fortune, and was now risking his life, all without hesitation, from duty, in silence.

Fix did not have the same thoughts, and could scarcely conceal his agitation. He walked feverishly up and down the platform, but soon resumed his outward composure. He now saw the folly of which he had been guilty in letting Fogg go alone. What! This man, whom he had just followed around the world, was permitted now to separate himself from him! He began to accuse and abuse himself, and, as if he were director of police, administered to himself a sound lecture for his greenness.

I have been an idiot!” he thought, “and this man will see it. He has gone, and won’t come back! But how is it that I, Fix, who have in my pocket a warrant for his arrest, have been so fascinated by him? Decidedly, I am nothing but an ass!”

So reasoned the detective, while the hours crept by all too slowly. He did not know what to do. Sometimes he was tempted to tell Aouda all; but he could not doubt how the young woman would receive his confidences. What course should he take? He thought of pursuing Fogg across the vast white plains; it did not seem impossible that he might overtake him. Footsteps were easily printed on the snow! But soon, under a new sheet, every imprint would be effaced.

Fix became discouraged. He felt a sort of insurmountable longing to abandon the game altogether. He could now leave Fort Kearney station, and pursue his journey homeward in peace.

Towards two o’clock in the afternoon, while it was snowing hard, long whistles were heard approaching from the east. A great shadow, preceded by a wild light, slowly advanced, appearing still larger through the mist, which gave it a fantastic aspect. No train was expected from the east, neither had there been time for the succour asked for by telegraph to arrive; the train from Omaha to San Francisco was not due till the next day. The mystery was soon explained.

The locomotive, which was slowly approaching with deafening whistles, was that which, having been detached from the train, had continued its route with such terrific rapidity, carrying off the unconscious engineer and stoker. It had run several miles, when, the fire becoming low for want of fuel, the steam had slackened; and it had finally stopped an hour after, some twenty miles beyond Fort Kearney. Neither the engineer nor the stoker was dead, and, after remaining for some time in their swoon, had come to themselves. The train had then stopped. The engineer, when he found himself in the desert, and the locomotive without cars, understood what had happened. He could not imagine how the locomotive had become separated from the train; but he did not doubt that the train left behind was in distress.

He did not hesitate what to do. It would be prudent to continue on to Omaha, for it would be dangerous to return to the train, which the Indians might still be engaged in pillaging. Nevertheless, he began to rebuild the fire in the furnace; the pressure again mounted, and the locomotive returned, running backwards to Fort Kearney. This it was which was whistling in the mist.

The travellers were glad to see the locomotive resume its place at the head of the train. They could now continue the journey so terribly interrupted.

Aouda, on seeing the locomotive come up, hurried out of the station, and asked the conductor, “Are you going to start?”

At once, madam.”

But the prisoners, our unfortunate fellow-travellers —”

I cannot interrupt the trip,” replied the conductor. “We are already three hours behind time.”

And when will another train pass here from San Francisco?”

To-morrow evening, madam.”

To-morrow evening! But then it will be too late! We must wait —”

It is impossible,” responded the conductor. “If you wish to go, please get in.”

I will not go,” said Aouda.

Fix had heard this conversation. A little while before, when there was no prospect of proceeding on the journey, he had made up his mind to leave Fort Kearney; but now that the train was there, ready to start, and he had only to take his seat in the car, an irresistible influence held him back. The station platform burned his feet, and he could not stir. The conflict in his mind again began; anger and failure stifled him. He wished to struggle on to the end.

Meanwhile the passengers and some of the wounded, among them Colonel Proctor, whose injuries were serious, had taken their places in the train. The buzzing of the over-heated boiler was heard, and the steam was escaping from the valves. The engineer whistled, the train started, and soon disappeared, mingling its white smoke with the eddies of the densely falling snow.

The detective had remained behind.

Several hours passed. The weather was dismal, and it was very cold. Fix sat motionless on a bench in the station; he might have been thought asleep. Aouda, despite the storm, kept coming out of the waiting-room, going to the end of the platform, and peering through the tempest of snow, as if to pierce the mist which narrowed the horizon around her, and to hear, if possible, some welcome sound. She heard and saw nothing. Then she would return, chilled through, to issue out again after the lapse of a few moments, but always in vain.

Evening came, and the little band had not returned. Where could they be? Had they found the Indians, and were they having a conflict with them, or were they still wandering amid the mist? The commander of the fort was anxious, though he tried to conceal his apprehensions. As night approached, the snow fell less plentifully, but it became intensely cold. Absolute silence rested on the plains. Neither flight of bird nor passing of beast troubled the perfect calm.

Throughout the night Aouda, full of sad forebodings, her heart stifled with anguish, wandered about on the verge of the plains. Her imagination carried her far off, and showed her innumerable dangers. What she suffered through the long hours it would be impossible to describe.

Fix remained stationary in the same place, but did not sleep. Once a man approached and spoke to him, and the detective merely replied by shaking his head.

Thus the night passed. At dawn, the half-extinguished disc of the sun rose above a misty horizon; but it was now possible to recognise objects two miles off. Phileas Fogg and the squad had gone southward; in the south all was still vacancy. It was then seven o’clock.

The captain, who was really alarmed, did not know what course to take.

Should he send another detachment to the rescue of the first? Should he sacrifice more men, with so few chances of saving those already sacrificed? His hesitation did not last long, however. Calling one of his lieutenants, he was on the point of ordering a reconnaissance, when gunshots were heard. Was it a signal? The soldiers rushed out of the fort, and half a mile off they perceived a little band returning in good order.

Mr. Fogg was marching at their head, and just behind him were Passepartout and the other two travellers, rescued from the Sioux.

They had met and fought the Indians ten miles south of Fort Kearney. Shortly before the detachment arrived, Passepartout and his companions had begun to struggle with their captors, three of whom the Frenchman had felled with his fists, when his master and the soldiers hastened up to their relief.

All were welcomed with joyful cries. Phileas Fogg distributed the reward he had promised to the soldiers, while Passepartout, not without reason, muttered to himself, “It must certainly be confessed that I cost my master dear!”

Fix, without saying a word, looked at Mr. Fogg, and it would have been difficult to analyse the thoughts which struggled within him. As for Aouda, she took her protector’s hand and pressed it in her own, too much moved to speak.

Meanwhile, Passepartout was looking about for the train; he thought he should find it there, ready to start for Omaha, and he hoped that the time lost might be regained.

The train! the train!” cried he.

Gone,” replied Fix.

And when does the next train pass here?” said Phileas Fogg.

Not till this evening.”

Ah!” returned the impassible gentleman quietly.

(to be continued)

Bridging the Golden Gate

Around the World in 80 Days

By Jules Verne, Chapter XXXI

In which Fix, the Detective, Considerably Furthers the Interests of Phileas Fogg

Phileas Fogg found himself twenty hours behind time. Passepartout, the involuntary cause of this delay, was desperate. He had ruined his master!

At this moment the detective approached Mr. Fogg, and, looking him intently in the face, said:

Seriously, sir, are you in great haste?”

Quite seriously.”

I have a purpose in asking,” resumed Fix. “Is it absolutely necessary that you should be in New York on the 11th, before nine o’clock in the evening, the time that the steamer leaves for Liverpool?”

It is absolutely necessary.”

And, if your journey had not been interrupted by these Indians, you would have reached New York on the morning of the 11th?”

Yes; with eleven hours to spare before the steamer left.”

Good! you are therefore twenty hours behind. Twelve from twenty leaves eight. You must regain eight hours. Do you wish to try to do so?”

On foot?” asked Mr. Fogg.

No; on a sledge,” replied Fix. “On a sledge with sails. A man has proposed such a method to me.”

It was the man who had spoken to Fix during the night, and whose offer he had refused.

Phileas Fogg did not reply at once; but Fix, having pointed out the man, who was walking up and down in front of the station, Mr. Fogg went up to him. An instant after, Mr. Fogg and the American, whose name was Mudge, entered a hut built just below the fort.

There Mr. Fogg examined a curious vehicle, a kind of frame on two long beams, a little raised in front like the runners of a sledge, and upon which there was room for five or six persons. A high mast was fixed on the frame, held firmly by metallic lashings, to which was attached a large brigantine sail. This mast held an iron stay upon which to hoist a jib-sail. Behind, a sort of rudder served to guide the vehicle. It was, in short, a sledge rigged like a sloop. During the winter, when the trains are blocked up by the snow, these sledges make extremely rapid journeys across the frozen plains from one station to another. Provided with more sails than a cutter, and with the wind behind them, they slip over the surface of the prairies with a speed equal if not superior to that of the express trains.

Mr. Fogg readily made a bargain with the owner of this land-craft. The wind was favourable, being fresh, and blowing from the west. The snow had hardened, and Mudge was very confident of being able to transport Mr. Fogg in a few hours to Omaha. Thence the trains eastward run frequently to Chicago and New York. It was not impossible that the lost time might yet be recovered; and such an opportunity was not to be rejected.

Not wishing to expose Aouda to the discomforts of travelling in the open air, Mr. Fogg proposed to leave her with Passepartout at Fort Kearney, the servant taking upon himself to escort her to Europe by a better route and under more favourable conditions. But Aouda refused to separate from Mr. Fogg, and Passepartout was delighted with her decision; for nothing could induce him to leave his master while Fix was with him.

It would be difficult to guess the detective’s thoughts. Was this conviction shaken by Phileas Fogg’s return, or did he still regard him as an exceedingly shrewd rascal, who, his journey round the world completed, would think himself absolutely safe in England? Perhaps Fix’s opinion of Phileas Fogg was somewhat modified; but he was nevertheless resolved to do his duty, and to hasten the return of the whole party to England as much as possible.

At eight o’clock the sledge was ready to start. The passengers took their places on it, and wrapped themselves up closely in their travelling-cloaks. The two great sails were hoisted, and under the pressure of the wind the sledge slid over the hardened snow with a velocity of forty miles an hour.

The distance between Fort Kearney and Omaha, as the birds fly, is at most two hundred miles. If the wind held good, the distance might be traversed in five hours; if no accident happened the sledge might reach Omaha by one o’clock.

What a journey! The travellers, huddled close together, could not speak for the cold, intensified by the rapidity at which they were going. The sledge sped on as lightly as a boat over the waves. When the breeze came skimming the earth the sledge seemed to be lifted off the ground by its sails. Mudge, who was at the rudder, kept in a straight line, and by a turn of his hand checked the lurches which the vehicle had a tendency to make. All the sails were up, and the jib was so arranged as not to screen the brigantine. A top-mast was hoisted, and another jib, held out to the wind, added its force to the other sails. Although the speed could not be exactly estimated, the sledge could not be going at less than forty miles an hour.

If nothing breaks,” said Mudge, “we shall get there!”

Mr. Fogg had made it for Mudge’s interest to reach Omaha within the time agreed on, by the offer of a handsome reward.

The prairie, across which the sledge was moving in a straight line, was as flat as a sea. It seemed like a vast frozen lake. The railroad which ran through this section ascended from the south-west to the north-west by Great Island, Columbus, an important Nebraska town, Schuyler, and Fremont, to Omaha. It followed throughout the right bank of the Platte River. The sledge, shortening this route, took a chord of the arc described by the railway. Mudge was not afraid of being stopped by the Platte River, because it was frozen. The road, then, was quite clear of obstacles, and Phileas Fogg had but two things to fear — an accident to the sledge, and a change or calm in the wind.

But the breeze, far from lessening its force, blew as if to bend the mast, which, however, the metallic lashings held firmly. These lashings, like the chords of a stringed instrument, resounded as if vibrated by a violin bow. The sledge slid along in the midst of a plaintively intense melody.

Those chords give the fifth and the octave,” said Mr. Fogg.

These were the only words he uttered during the journey. Aouda, cosily packed in furs and cloaks, was sheltered as much as possible from the attacks of the freezing wind. As for Passepartout, his face was as red as the sun’s disc when it sets in the mist, and he laboriously inhaled the biting air. With his natural buoyancy of spirits, he began to hope again. They would reach New York on the evening, if not on the morning, of the 11th, and there was still some chances that it would be before the steamer sailed for Liverpool.

Passepartout even felt a strong desire to grasp his ally, Fix, by the hand. He remembered that it was the detective who procured the sledge, the only means of reaching Omaha in time; but, checked by some presentiment, he kept his usual reserve. One thing, however, Passepartout would never forget, and that was the sacrifice which Mr. Fogg had made, without hesitation, to rescue him from the Sioux. Mr. Fogg had risked his fortune and his life. No! His servant would never forget that!

While each of the party was absorbed in reflections so different, the sledge flew past over the vast carpet of snow. The creeks it passed over were not perceived. Fields and streams disappeared under the uniform whiteness. The plain was absolutely deserted. Between the Union Pacific road and the branch which unites Kearney with Saint Joseph it formed a great uninhabited island. Neither village, station, nor fort appeared. From time to time they sped by some phantom-like tree, whose white skeleton twisted and rattled in the wind. Sometimes flocks of wild birds rose, or bands of gaunt, famished, ferocious prairie-wolves ran howling after the sledge. Passepartout, revolver in hand, held himself ready to fire on those which came too near. Had an accident then happened to the sledge, the travellers, attacked by these beasts, would have been in the most terrible danger; but it held on its even course, soon gained on the wolves, and ere long left the howling band at a safe distance behind.

About noon Mudge perceived by certain landmarks that he was crossing the Platte River. He said nothing, but he felt certain that he was now within twenty miles of Omaha. In less than an hour he left the rudder and furled his sails, whilst the sledge, carried forward by the great impetus the wind had given it, went on half a mile further with its sails unspread.

It stopped at last, and Mudge, pointing to a mass of roofs white with snow, said: “We have got there!”

Arrived! Arrived at the station which is in daily communication, by numerous trains, with the Atlantic seaboard!

Passepartout and Fix jumped off, stretched their stiffened limbs, and aided Mr. Fogg and the young woman to descend from the sledge. Phileas Fogg generously rewarded Mudge, whose hand Passepartout warmly grasped, and the party directed their steps to the Omaha railway station.

The Pacific Railroad proper finds its terminus at this important Nebraska town. Omaha is connected with Chicago by the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad, which runs directly east, and passes fifty stations.

A train was ready to start when Mr. Fogg and his party reached the station, and they only had time to get into the cars. They had seen nothing of Omaha; but Passepartout confessed to himself that this was not to be regretted, as they were not travelling to see the sights.

The train passed rapidly across the State of Iowa, by Council Bluffs, Des Moines, and Iowa City. During the night it crossed the Mississippi at Davenport, and by Rock Island entered Illinois. The next day, which was the 10th, at four o’clock in the evening, it reached Chicago, already risen from its ruins, and more proudly seated than ever on the borders of its beautiful Lake Michigan.

Nine hundred miles separated Chicago from New York; but trains are not wanting at Chicago. Mr. Fogg passed at once from one to the other, and the locomotive of the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne, and Chicago Railway left at full speed, as if it fully comprehended that that gentleman had no time to lose. It traversed Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey like a flash, rushing through towns with antique names, some of which had streets and car-tracks, but as yet no houses. At last the Hudson came into view; and, at a quarter-past eleven in the evening of the 11th, the train stopped in the station on the right bank of the river, before the very pier of the Cunard line.

The China, for Liverpool, had started three-quarters of an hour before!

(to be continued)

Conquerors of the Impossible

'All Men are Builders at Heart'

The Spirit of Saint Louis

Lindbergh's Transatlantic Flight

Watch: The Spirit of Saint Louis [click to watch]

When I was a boy, I remember reading Charles Lindbergh’s The Spirit of Saint Louis. It is a hopeful book and sets a young person to thinking about his or her own goals and aspirations. We watched men go to the moon. Amazing achievements, rooted in IMAGO DEI – our creation in the Divine Image, served to inspire us. Sadly, we’ve lost that part of the great story. At the end of today’s issue John Stonestreet will talk about the message young people often hear today. Nihilism has replaced the optimism that characterized the fiction of our day.

For our part, I believe people of Faith have been all too quick to accept the pessimism of our day. We look forward to future bliss, but forget that the Divine promises to restore all things and that our labor in the Lord is not in vain. We forget that our inventiveness is part of the Salvation message. We are made in the Divine Image. That includes the creative spark that drives us to invent new technologies and solve problems. It makes us work to fight starvation and dig wells. It leads us to do great things.

To be sure, it can be overworked into pride and arrogance, but in that regard it is like any good thing pushed to excess. I once read a Christian book where the author said that primitive societies were ‘better’ because people were not pushed as they are in Western society. They had more time for family and contemplation the author continued. The more I pondered the author’s point, the more I wondered: “has he actually LIVED in such a culture?” As a Western missionary, he had indeed inserted himself into such a place but it was clear that he was a visitor and his Western support gave him the leisure to enjoy it.

Had he truly lived as one of such a culture, he would have seen the reality of a failed hunt and hungry children. He would have known the pain of infant mortality, often caused by contaminated water that a modern well would have eliminated. He might have experienced the terror of tribal war. In the end I determined that I was happier with the ‘problems’ of my own culture. I bring this story up merely to point out that we may not truly appreciate much of what inspiration has done to enrich our own lives. If we do not appreciate it, we probably do not pass the baton to our children.

We as a people need a good shot of hope. An honest study of our history might just give us more of that than we might imagine. In light of the latest acts of evil in our world, the need to teach hope and goodness is imperative! To that end I present the stories that I do.

In the 1957 film, The Spirit of Saint Louis, Ryan Aircraft employees are depicted signing the cowling.

Around the World in 80 Days

By Jules Verne, Chapter XXXII

In which Phileas Fogg Engages in a Direct Struggle with Bad Fortune

The China, in leaving, seemed to have carried off Phileas Fogg’s last hope. None of the other steamers were able to serve his projects. The Pereire, of the French Transatlantic Company, whose admirable steamers are equal to any in speed and comfort, did not leave until the 14th; the Hamburg boats did not go directly to Liverpool or London, but to Havre; and the additional trip from Havre to Southampton would render Phileas Fogg’s last efforts of no avail. The Inman steamer did not depart till the next day, and could not cross the Atlantic in time to save the wager.

Mr. Fogg learned all this in consulting his Bradshaw, which gave him the daily movements of the trans-Atlantic steamers.

Passepartout was crushed; it overwhelmed him to lose the boat by three-quarters of an hour. It was his fault, for, instead of helping his master, he had not ceased putting obstacles in his path! And when he recalled all the incidents of the tour, when he counted up the sums expended in pure loss and on his own account, when he thought that the immense stake, added to the heavy charges of this useless journey, would completely ruin Mr. Fogg, he overwhelmed himself with bitter self-accusations. Mr. Fogg, however, did not reproach him; and, on leaving the Cunard pier, only said: “We will consult about what is best to-morrow. Come.”

The party crossed the Hudson in the Jersey City ferryboat, and drove in a carriage to the St. Nicholas Hotel, on Broadway. Rooms were engaged, and the night passed, briefly to Phileas Fogg, who slept profoundly, but very long to Aouda and the others, whose agitation did not permit them to rest.

The next day was the 12th of December. From seven in the morning of the 12th to a quarter before nine in the evening of the 21st there were nine days, thirteen hours, and forty-five minutes. If Phileas Fogg had left in the China, one of the fastest steamers on the Atlantic, he would have reached Liverpool, and then London, within the period agreed upon.

Mr. Fogg left the hotel alone, after giving Passepartout instructions to await his return, and inform Aouda to be ready at an instant’s notice. He proceeded to the banks of the Hudson, and looked about among the vessels moored or anchored in the river, for any that were about to depart. Several had departure signals, and were preparing to put to sea at morning tide; for in this immense and admirable port there is not one day in a hundred that vessels do not set out for every quarter of the globe. But they were mostly sailing vessels, of which, of course, Phileas Fogg could make no use.

He seemed about to give up all hope, when he espied, anchored at the Battery, a cable’s length off at most, a trading vessel, with a screw, well-shaped, whose funnel, puffing a cloud of smoke, indicated that she was getting ready for departure.

Phileas Fogg hailed a boat, got into it, and soon found himself on board the Henrietta, iron-hulled, wood-built above. He ascended to the deck, and asked for the captain, who forthwith presented himself. He was a man of fifty, a sort of sea-wolf, with big eyes, a complexion of oxidised copper, red hair and thick neck, and a growling voice.

The captain?” asked Mr. Fogg.

I am the captain.”

I am Phileas Fogg, of London.”

And I am Andrew Speedy, of Cardiff.”

You are going to put to sea?”

In an hour.”

You are bound for —”

Bordeaux.”

And your cargo?”

No freight. Going in ballast.”

Have you any passengers?”

No passengers. Never have passengers. Too much in the way.”

Is your vessel a swift one?”

Between eleven and twelve knots. The Henrietta, well known.”

Will you carry me and three other persons to Liverpool?”

To Liverpool? Why not to China?”

I said Liverpool.”

No!”

No?”

No. I am setting out for Bordeaux, and shall go to Bordeaux.”

Money is no object?”

None.”

The captain spoke in a tone which did not admit of a reply.

But the owners of the Henrietta —” resumed Phileas Fogg.

The owners are myself,” replied the captain. “The vessel belongs to me.”

I will freight it for you.”

No.”

I will buy it of you.”

No.”

Phileas Fogg did not betray the least disappointment; but the situation was a grave one. It was not at New York as at Hong Kong, nor with the captain of the Henrietta as with the captain of the Tankadere. Up to this time money had smoothed away every obstacle. Now money failed.

Still, some means must be found to cross the Atlantic on a boat, unless by balloon — which would have been venturesome, besides not being capable of being put in practice. It seemed that Phileas Fogg had an idea, for he said to the captain, “Well, will you carry me to Bordeaux?”

No, not if you paid me two hundred dollars.”

I offer you two thousand.”

Apiece?”

Apiece.”

And there are four of you?”

Four.”

Captain Speedy began to scratch his head. There were eight thousand dollars to gain, without changing his route; for which it was well worth conquering the repugnance he had for all kinds of passengers. Besides, passenger’s at two thousand dollars are no longer passengers, but valuable merchandise. “I start at nine o’clock,” said Captain Speedy, simply. “Are you and your party ready?”

We will be on board at nine o’clock,” replied, no less simply, Mr. Fogg.

It was half-past eight. To disembark from the Henrietta, jump into a hack, hurry to the St. Nicholas, and return with Aouda, Passepartout, and even the inseparable Fix was the work of a brief time, and was performed by Mr. Fogg with the coolness which never abandoned him. They were on board when the Henrietta made ready to weigh anchor.

When Passepartout heard what this last voyage was going to cost, he uttered a prolonged “Oh!” which extended throughout his vocal gamut.

As for Fix, he said to himself that the Bank of England would certainly not come out of this affair well indemnified. When they reached England, even if Mr. Fogg did not throw some handfuls of bank-bills into the sea, more than seven thousand pounds would have been spent!

(to be continued)

Leaves in a stream, Shenandoah National Park.

Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Around the World in 80 Days

By Jules Verne, Chapter XXXIII

In which Phileas Fogg Shows Himself Equal to the Occasion

An hour after, the Henrietta passed the lighthouse which marks the entrance of the Hudson, turned the point of Sandy Hook, and put to sea. During the day she skirted Long Island, passed Fire Island, and directed her course rapidly eastward.

At noon the next day, a man mounted the bridge to ascertain the vessel’s position. It might be thought that this was Captain Speedy. Not the least in the world. It was Phileas Fogg, Esquire. As for Captain Speedy, he was shut up in his cabin under lock and key, and was uttering loud cries, which signified an anger at once pardonable and excessive.

What had happened was very simple. Phileas Fogg wished to go to Liverpool, but the captain would not carry him there. Then Phileas Fogg had taken passage for Bordeaux, and, during the thirty hours he had been on board, had so shrewdly managed with his banknotes that the sailors and stokers, who were only an occasional crew, and were not on the best terms with the captain, went over to him in a body. This was why Phileas Fogg was in command instead of Captain Speedy; why the captain was a prisoner in his cabin; and why, in short, the Henrietta was directing her course towards Liverpool. It was very clear, to see Mr. Fogg manage the craft, that he had been a sailor.

How the adventure ended will be seen anon. Aouda was anxious, though she said nothing. As for Passepartout, he thought Mr. Fogg’s manoeuvre simply glorious. The captain had said “between eleven and twelve knots,” and the Henrietta confirmed his prediction.

If, then — for there were “ifs” still — the sea did not become too boisterous, if the wind did not veer round to the east, if no accident happened to the boat or its machinery, the Henrietta might cross the three thousand miles from New York to Liverpool in the nine days, between the 12th and the 21st of December. It is true that, once arrived, the affair on board the Henrietta, added to that of the Bank of England, might create more difficulties for Mr. Fogg than he imagined or could desire.

During the first days, they went along smoothly enough. The sea was not very unpropitious, the wind seemed stationary in the north-east, the sails were hoisted, and the Henrietta ploughed across the waves like a real trans-Atlantic steamer.

Passepartout was delighted. His master’s last exploit, the consequences of which he ignored, enchanted him. Never had the crew seen so jolly and dexterous a fellow. He formed warm friendships with the sailors, and amazed them with his acrobatic feats. He thought they managed the vessel like gentlemen, and that the stokers fired up like heroes. His loquacious good-humour infected everyone. He had forgotten the past, its vexations and delays. He only thought of the end, so nearly accomplished; and sometimes he boiled over with impatience, as if heated by the furnaces of the Henrietta. Often, also, the worthy fellow revolved around Fix, looking at him with a keen, distrustful eye; but he did not speak to him, for their old intimacy no longer existed.

Fix, it must be confessed, understood nothing of what was going on. The conquest of the Henrietta, the bribery of the crew, Fogg managing the boat like a skilled seaman, amazed and confused him. He did not know what to think. For, after all, a man who began by stealing fifty-five thousand pounds might end by stealing a vessel; and Fix was not unnaturally inclined to conclude that the Henrietta under Fogg’s command, was not going to Liverpool at all, but to some part of the world where the robber, turned into a pirate, would quietly put himself in safety. The conjecture was at least a plausible one, and the detective began to seriously regret that he had embarked on the affair.

As for Captain Speedy, he continued to howl and growl in his cabin; and Passepartout, whose duty it was to carry him his meals, courageous as he was, took the greatest precautions. Mr. Fogg did not seem even to know that there was a captain on board.

On the 13th they passed the edge of the Banks of Newfoundland, a dangerous locality; during the winter, especially, there are frequent fogs and heavy gales of wind. Ever since the evening before the barometer, suddenly falling, had indicated an approaching change in the atmosphere; and during the night the temperature varied, the cold became sharper, and the wind veered to the south-east.

This was a misfortune. Mr. Fogg, in order not to deviate from his course, furled his sails and increased the force of the steam; but the vessel’s speed slackened, owing to the state of the sea, the long waves of which broke against the stern. She pitched violently, and this retarded her progress. The breeze little by little swelled into a tempest, and it was to be feared that the Henrietta might not be able to maintain herself upright on the waves.

Passepartout’s visage darkened with the skies, and for two days the poor fellow experienced constant fright. But Phileas Fogg was a bold mariner, and knew how to maintain headway against the sea; and he kept on his course, without even decreasing his steam. The Henrietta, when she could not rise upon the waves, crossed them, swamping her deck, but passing safely. Sometinies the screw rose out of the water, beating its protruding end, when a mountain of water raised the stern above the waves; but the craft always kept straight ahead.

The wind, however, did not grow as boisterous as might have been feared; it was not one of those tempests which burst, and rush on with a speed of ninety miles an hour. It continued fresh, but, unhappily, it remained obstinately in the south-east, rendering the sails useless.

The 16th of December was the seventy-fifth day since Phileas Fogg’s departure from London, and the Henrietta had not yet been seriously delayed. Half of the voyage was almost accomplished, and the worst localities had been passed. In summer, success would have been well-nigh certain. In winter, they were at the mercy of the bad season. Passepartout said nothing; but he cherished hope in secret, and comforted himself with the reflection that, if the wind failed them, they might still count on the steam.

On this day the engineer came on deck, went up to Mr. Fogg, and began to speak earnestly with him. Without knowing why it was a presentiment, perhaps Passepartout became vaguely uneasy. He would have given one of his ears to hear with the other what the engineer was saying. He finally managed to catch a few words, and was sure he heard his master say, “You are certain of what you tell me?”

Certain, sir,” replied the engineer. “You must remember that, since we started, we have kept up hot fires in all our furnaces, and, though we had coal enough to go on short steam from New York to Bordeaux, we haven’t enough to go with all steam from New York to Liverpool.” “I will consider,” replied Mr. Fogg.

Passepartout understood it all; he was seized with mortal anxiety. The coal was giving out! “Ah, if my master can get over that,” muttered he, “he’ll be a famous man!” He could not help imparting to Fix what he had overheard.

Then you believe that we really are going to Liverpool?”

Of course.”

Ass!” replied the detective, shrugging his shoulders and turning on his heel.

Passepartout was on the point of vigorously resenting the epithet, the reason of which he could not for the life of him comprehend; but he reflected that the unfortunate Fix was probably very much disappointed and humiliated in his self-esteem, after having so awkwardly followed a false scent around the world, and refrained.

And now what course would Phileas Fogg adopt? It was difficult to imagine. Nevertheless he seemed to have decided upon one, for that evening he sent for the engineer, and said to him, “Feed all the fires until the coal is exhausted.”

A few moments after, the funnel of the Henrietta vomited forth torrents of smoke. The vessel continued to proceed with all steam on; but on the 18th, the engineer, as he had predicted, announced that the coal would give out in the course of the day.

Do not let the fires go down,” replied Mr. Fogg. “Keep them up to the last. Let the valves be filled.”

Towards noon Phileas Fogg, having ascertained their position, called Passepartout, and ordered him to go for Captain Speedy. It was as if the honest fellow had been commanded to unchain a tiger. He went to the poop, saying to himself, “He will be like a madman!”

In a few moments, with cries and oaths, a bomb appeared on the poop-deck. The bomb was Captain Speedy. It was clear that he was on the point of bursting. “Where are we?” were the first words his anger permitted him to utter. Had the poor man be an apoplectic, he could never have recovered from his paroxysm of wrath.

Where are we?” he repeated, with purple face.

Seven hundred and seven miles from Liverpool,” replied Mr. Fogg, with imperturbable calmness.

Pirate!” cried Captain Speedy.

I have sent for you, sir —”

Pickaroon!”

“— sir,” continued Mr. Fogg, “to ask you to sell me your vessel.”

No! By all the devils, no!”

But I shall be obliged to burn her.”

Burn the Henrietta!”

Yes; at least the upper part of her. The coal has given out.”

Burn my vessel!” cried Captain Speedy, who could scarcely pronounce the words. “A vessel worth fifty thousand dollars!”

Here are sixty thousand,” replied Phileas Fogg, handing the captain a roll of bank-bills. This had a prodigious effect on Andrew Speedy. An American can scarcely remain unmoved at the sight of sixty thousand dollars. The captain forgot in an instant his anger, his imprisonment, and all his grudges against his passenger. The Henrietta was twenty years old; it was a great bargain. The bomb would not go off after all. Mr. Fogg had taken away the match.

And I shall still have the iron hull,” said the captain in a softer tone.

The iron hull and the engine. Is it agreed?”

Agreed.”

And Andrew Speedy, seizing the banknotes, counted them and consigned them to his pocket.

During this colloquy, Passepartout was as white as a sheet, and Fix seemed on the point of having an apoplectic fit. Nearly twenty thousand pounds had been expended, and Fogg left the hull and engine to the captain, that is, near the whole value of the craft! It was true, however, that fifty-five thousand pounds had been stolen from the Bank.

When Andrew Speedy had pocketed the money, Mr. Fogg said to him, “Don’t let this astonish you, sir. You must know that I shall lose twenty thousand pounds, unless I arrive in London by a quarter before nine on the evening of the 21st of December. I missed the steamer at New York, and as you refused to take me to Liverpool —”

And I did well!” cried Andrew Speedy; “for I have gained at least forty thousand dollars by it!” He added, more sedately, “Do you know one thing, Captain —”

Fogg.”

Captain Fogg, you’ve got something of the Yankee about you.”

And, having paid his passenger what he considered a high compliment, he was going away, when Mr. Fogg said, “The vessel now belongs to me?”

Certainly, from the keel to the truck of the masts — all the wood, that is.”

Very well. Have the interior seats, bunks, and frames pulled down, and burn them.”

It was necessary to have dry wood to keep the steam up to the adequate pressure, and on that day the poop, cabins, bunks, and the spare deck were sacrificed. On the next day, the 19th of December, the masts, rafts, and spars were burned; the crew worked lustily, keeping up the fires. Passepartout hewed, cut, and sawed away with all his might. There was a perfect rage for demolition.

The railings, fittings, the greater part of the deck, and top sides disappeared on the 20th, and the Henrietta was now only a flat hulk. But on this day they sighted the Irish coast and Fastnet Light. By ten in the evening they were passing Queenstown. Phileas Fogg had only twenty-four hours more in which to get to London; that length of time was necessary to reach Liverpool, with all steam on. And the steam was about to give out altogether!

Sir,” said Captain Speedy, who was now deeply interested in Mr. Fogg’s project, “I really commiserate you. Everything is against you. We are only opposite Queenstown.”

Ah,” said Mr. Fogg, “is that place where we see the lights Queenstown?”

Yes.”

Can we enter the harbour?”

Not under three hours. Only at high tide.”

Stay,” replied Mr. Fogg calmly, without betraying in his features that by a supreme inspiration he was about to attempt once more to conquer ill-fortune.

Queenstown is the Irish port at which the trans-Atlantic steamers stop to put off the mails. These mails are carried to Dublin by express trains always held in readiness to start; from Dublin they are sent on to Liverpool by the most rapid boats, and thus gain twelve hours on the Atlantic steamers.

Phileas Fogg counted on gaining twelve hours in the same way. Instead of arriving at Liverpool the next evening by the Henrietta, he would be there by noon, and would therefore have time to reach London before a quarter before nine in the evening.

The Henrietta entered Queenstown Harbour at one o’clock in the morning, it then being high tide; and Phileas Fogg, after being grasped heartily by the hand by Captain Speedy, left that gentleman on the levelled hulk of his craft, which was still worth half what he had sold it for.

The party went on shore at once. Fix was greatly tempted to arrest Mr. Fogg on the spot; but he did not. Why? What struggle was going on within him? Had he changed his mind about “his man”? Did he understand that he had made a grave mistake? He did not, however, abandon Mr. Fogg. They all got upon the train, which was just ready to start, at half-past one; at dawn of day they were in Dublin; and they lost no time in embarking on a steamer which, disdaining to rise upon the waves, invariably cut through them.

Phileas Fogg at last disembarked on the Liverpool quay, at twenty minutes before twelve, 21st December. He was only six hours distant from London.

But at this moment Fix came up, put his hand upon Mr. Fogg’s shoulder, and, showing his warrant, said, “You are really Phileas Fogg?”

I am.”

I arrest you in the Queen’s name!”

(to be continued)

The Bridge Builder's Tale

Chapter Five: Charles Alton Ellis and Strauss

1.Invention is rarely created in a vacuum. 2. Always read your colleague's/competitor's white papers. 3. The flashy guy who gets all the big grants just sometimes aint all that smart, and 4. Persistence, hard work and humility is always a great combination in any situation." -- M. K. Wharton

Our world of today revolves around things which at one time couldn’t be done because they were supposedly beyond the limits of human endeavor….don’t be afraid to dream.” -- Joseph Baermann Strauss

The building of the Bering Strait Bridge had involved the consideration of a dynamic design problem of epic proportions. Though investors thought Zimmerman's proposal a simple expansion of projects done elsewhere, it was in truth a project that involved new ventures into the unknown. Years before, someone had proposed a tunnel between Russia and Alaska. The fact that the sea floor itself was in motion made that an impractical solution. Add to that the strong ice-filled currents of the Strait and the vicious storms that sometimes swirled through and you had a lot of problems that had to be solved. Computer modeling always seemed to miss some subtle, but important part of the puzzle. O'Malley had given up pretty quickly on doing so, as Rupert had resorted to scaled down models of his bridge sections which he placed into the actual currents of the Strait. Detailed structural analysis on real models taught the designers far more than electronic simulation.

The design process had precedent in the United States space program in the 1960's. When President John F. Kennedy proposed putting a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth, he was using German ICBM technology and rockets that had about a 50% chance of actually surviving launch. American engineers had developed the new field of aerospace structural dynamics to refine the rockets. Their tools were machines that simulated the vibrations and stresses that actually occurred during launch. An engineer in Greenbelt, Maryland had actually created what he called the "Launch Phase Simulator." It was a giant centrifuge, which simulated the increased gravity forces of lift-off. There was a vibration machine in a vacuum chamber on the end of the centrifuge arm. Inside the vacuum chamber were lamps to simulate sun exposure and cryogenic tubing to simulate the cold.

The combined stresses that could be studied using this method allowed engineers to see what they were missing in analyzing isolated phenomena. American rocket technology moved forward to a more dependable launch vehicle. Rupert found some of the old documentation of this work and he, Martin and Elizabeth studied it to develop their own methodology.

Zimmerman had listened in horror to the broadcast when the space shuttle Challenger blew apart. A cold morning had caused an "o" ring in a solid fuel booster to compress, creating a leak where the heat of combustion caused the explosion of the fuel tank. Apparently the computer model had missed this. The old "bench-test" guys had been replaced by the "whiz kids" with computer analysis. One engineer of the old school had, in fact, tried to delay the launch. He suspected something like this could occur, but could only share his speculation. He was overruled and the fateful launch went on.

The shuttle Columbia was destroyed as her heat shield of fragile ceramic tiles had been unknowingly damaged during launch. Re-entering the Earth's atmosphere, the breach in her shield had caused the heat of reentry to destroy the ship and her crew. Space flight was never without risk, astronauts Grissom, Chaffee and White had perished in a fire that engulfed their Apollo I spacecraft. Apparently a spark ignited their oxygen-rich atmosphere inside the ship during a routine preflight systems check. Apollo XI almost didn't make it off the moon. One of the astronauts had broken an essential fuse going in or out of the craft. 'Buzz' Aldren had used a ball-point pen to facilitate a makeshift repair. Without that pen the astronauts would have been stranded on the moon!

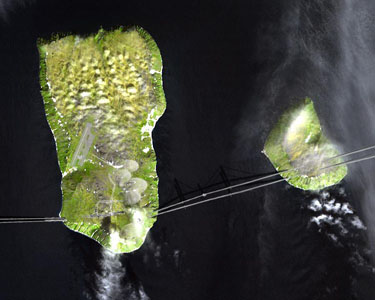

The Diomedes as seen in satellite imagery.

Bridge building itself had a long history of danger. Washington Augustus Roebling, son of John Roebling who designed the beautiful Brooklyn Bridge, engineered two pneumatic caissons that allowed men to build the foundations of the two towers. In 1870 a fire broke out in one of the caissons and Roebling was able to extinguish it. He did suffer from the bends, or decompression sickness as a result of his time in the cassions, forcing him to supervise much of the work from his home overlooking the bridge. The towers and spans of such projects were dangerous as well. “Bridgemen” at the turn of the century were known for reckless daredevilry.

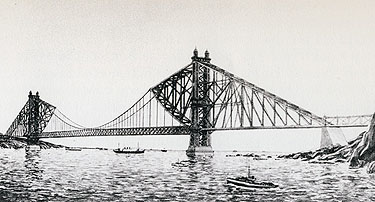

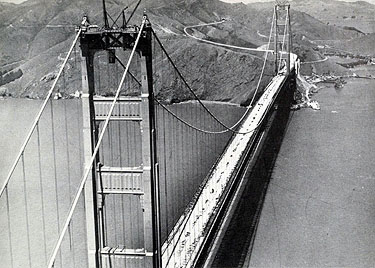

Zimmerman admired the work of Joseph Baermann Strauss, chief engineer of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. [1.] Strauss' father was a Bavarian painter and his mother was a musician. He grew up in a home that looked out on the 1,057-foot-long Covington-Cincinnati bridge. The bridge was, at the time it opened, the longest suspension bridge in the world. Hailed as a visionary, poet, builder and dreamer, young Joseph injured himself in an attempt to play for the university football team. Legend has it that he took in the view of the great bridge from his bed as he recovered, inspiring his future career. Strauss’ undergraduate thesis, presented in 1892, actually proposed a bridge across the Bering Strait, connecting North America and Asia. [2.]

His magnum opus would be the Golden Gate Bridge, completed in 1937. Strauss was appalled that a project at the time typically lost one life for every million dollars spent according to the actuaries. Looking at a $40 million dollar project, he refused to lose the lives of forty men to do it. Strauss put into effect the most rigorous safety code ever enforced on a project. He required all workers to wear Edward W. Bullard’s hard hats, first created for coal miners. The bridge workers all received a modified version of the Bullard hat. Respirators, glare-free safety goggles and special hand and face cream to protect workers from the cruel winds were also required.

A safety net was suspended beneath the roadway during construction and is credited for saving nineteen lives. Strauss even built an on-site field hospital at Fort Point. The men were fed carefully formulated diets, believed to help fight dizziness. Hung-over workers received a specially formulated “sauerkraut cure.” Most important, Strauss strictly enforced his rules: “On the Golden Gate Bridge, we had the idea we could cheat death by providing every known safety device for workers,” he wrote in 1937 for The Saturday Evening Post. “To the annoyance of the daredevils who loved to stunt at the end of the cables, far out in space, we fired any man we caught stunting on the job.” In spite of such diligence, eleven lives were still lost. Most of the men died when a scaffolding collapsed and fell through the safety net.

Joseph Strauss' original design for the Golden Gate Bridge.

Though he did obtain a reputation for great safety engineering, Strauss failed in some important areas. His work prior to the Golden Gate Bridge was in building smaller projects and this time he may have taken on more than he could handle. His initial proposal was an awkward combination of truss and suspension bridge and the design was rejected. Undaunted, he hired Charles Alton Ellis to complete the design. Ellis drew out the graceful structure that was actually built. In Ellis, Strauss had his Martin O'Malley to round out his team; But there was a problem: Ellis was a serious engineer and Strauss grew impatient as the conscientious Ellis exhaustively checked his own calculations. Strauss had made Ellis Vice-president of the operation and had originally lauded the skills of his colleague, but there came a time when Strauss told Ellis to go on a long vacation. He then wrote Ellis a letter telling him not to come back. When the bridge opened in 1937 there was no attribution made to Ellis for three years of excellent work.

Strauss' show of ego might well have resulted in a tragedy similar to the 2007 collapse of the I35W Bridge over the Saint Anthony Falls of the Mississippi River in Minneapolis, Minnesota. During the evening rush hour, it suddenly collapsed, killing 13 people and injuring 145. The reason was an improperly specified gusset plate. The error was not found prior to construction. Ellis continued to check his calculations, working unpaid, and presented areas of concern to the Golden Gate Bridge design team. Needless to say; Zimmerman and the O'Malleys found this a sobering and important lesson. They came to treasure their collaboration and collective abilities all the more as they faced new challenges in their own work.

Elizabeth, Martin and Rupert simulated their own macabre set of 'occurrences' in an effort to ensure that the risks of their great bridge would be minimal. After they had constructed half-scale models of their pre-manufactured bridge sections and placed them in the strait they simulated ship collisions, terrorist explosions, even submarine cutting of the anchor cables. They built a shear-factor into the tube sidewalls to direct the energy of an intentional explosion outward, hopefully saving the structure itself. The trade-off was that a large collision, such as the one that occurred when Abdul jackknifed, also would break through the wall. They simulated the repair and replacement of damaged sections in winter currents. Their plan was to initially manufacture "extra" sections to replace any that became damaged beyond repair or destroyed. The "extra" sections would eventually become the twin span and then more sections would be fabricated on a "pay as you go" plan to become a third crossing over St. Lawrence Island.

Here Rupert looked at how the Bospherous had been bridged in Turkey. The initial span, built in the Twentieth Century, had required heavy security in the volatile Middle-East. Eventually a second "beltway" span sealed the reality that the Bospherous could always be crossed. Elizabeth noted that people who enjoyed the prosperity of commerce were less easily radicalized. She planned to spread the wealth that resulted from her father's great work.

When his initial design for the Golden Gate Bridge was rejected, Joseph Strauss hired engineer: Charles Alton Ellis to create the design that was actually constructed, shown here in this California Highways and Public Works Photograph from 1937.

Construction on the Alcan Highway. The road was built in 1942 and completed within a year as part of the war effort.

M56 near Yakutsk prior to being upgraded as part of the Bering Highway.

Photo by Andrey Laskov.

The twin spans of the Bering Strait Bridge. The original span (closest) is the Charles Alton Ellis Memorial Bridge. The second span is the Joseph Baermann Strauss Memorial Bridge.

Preliminary Grading on Little Diomede.

The 'Launch Phase Simulator' at Goddard Spaceflight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

NASA Photo

(to be continued) [click to read]

Copyright © 2015, The Kirchman Studio, all rights reserved

Seven Days

Photos by Bob Kirchman

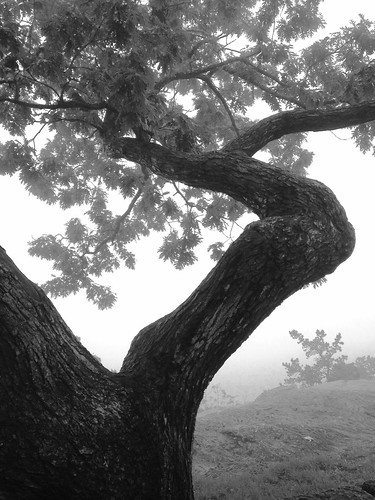

Summer.

Autumn.

Winter.

Spring.

Summer.

Autumn.

Winter.

I think the thrill of the Pagan stories and of romance may be due to the fact that they are mere beginnings—the first, faint whisper of the wind from beyond the world—while Christianity is the thing itself: and no thing, when you have really started on it, can have for you then and there just the same thrill as the first hint. For example, the experience of being married and bringing up a family cannot have the old bittersweet of first falling in love. But it is futile (and, I think, wicked) to go on trying to get the old thrill again: you must go forward and not backward. Any real advance will in its turn be ushered in by a new thrill, different from the old: doomed in its turn to disappear and to become in its turn a temptation to retrogression. Delight is a bell that rings as you set your foot on the first step of a new flight of stairs leading upwards. Once you have started climbing you will notice only the hard work: it is when you have reached the landing and catch sight of the new stair that you may expect the bell again. This is only an idea, and may be all rot: but it seems to fit in pretty well with the general law (thrills also must die to live) of autumn and spring, sleep and waking, death and resurrection, and ‘Whosoever loseth his life, shall save it.‘” – C. S. Lewis, Collected Letters

We are, not metaphorically but in very truth, a Divine work of art, something that God is making, and therefore something with which He will not be satisfied until it has a certain character. Here again we come up against what I have called the “intolerable compliment.” Over a sketch made idly to amuse a child, an artist may not take much trouble: he may be content to let it go even though it is not exactly as he meant it to be. But over the great picture of his life—the work which he loves, though in a different fashion, as intensely as a man loves a woman or a mother a child—he will take endless trouble—and would doubtless, thereby give endless trouble to the picture if it were sentient. One can imagine a sentient picture, after being rubbed and scraped and re-commenced for the tenth time, wishing that it were only a thumb-nail sketch whose making was over in a minute. In the same way, it is natural for us to wish that God had designed for us a less glorious and less arduous destiny; but then we are wishing not for more love but for less.” ― C.S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain

The problem of reconciling human suffering with the existence of a God who loves, is only insoluble so long as we attach a trivial meaning to the word "love", and look on things as if man were the centre of them. Man is not the centre. God does not exist for the sake of man. Man does not exist for his own sake. "Thou hast created all things, and for thy pleasure they are and were created." We were made not primarily that we may love God (though we were made for that too) but that God may love us, that we may become objects in which the divine love may rest "well pleased".” ― C.S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain

From Dystopia to Nihilism

Literature Aimed at Young Adults Promotes Despair

[click to read]

by: John Stonestreet and Roberto Rivera

What are your teens reading these days? You really should find out. Especially if they’re into the newest trend in young adult fiction.

For the first decade or so of the 21st century, the hottest trend in young adult fiction was dystopian novels. Book series like “The Hunger Games,” “The Maze Runner,” and “Divergent” sold tens of millions of copies, were turned into successful film franchises, and spawned so many imitators that the genre became, as Vox.com put it, a “cliché.”

While there are still plenty of young adult dystopias being written, a new genre seems to be emerging—one that will make us look back on the young adult dystopia boom as the “good old days.”

That genre is teen suicide.

In a recent article in Vox, Constance Grady pointed out that young adult dystopias have been “a license to print money” for publishers. Though there are many theories about why the genre exploded, virtually everyone agrees that the popularity of the books, like pop culture in general, reflects the readers’ concerns and moods. [read more]

The Church Resilient

Why Church Shootings Don't Intimidate

[click to read]

By Russell Moore

Eternal life cannot be overcome by death. And over that church will be a cross." [read more] ht/M. K. Hand

An ordinary simple Christian kneels down to say his prayers. He is trying to get into touch with God. But if he is a Christian he knows that what is prompting him to pray is also God: God, so to speak, inside him. But he also knows that all his real knowledge of God comes through Christ, the Man who was God—that Christ is standing beside him, helping him to pray, praying for him. You see what is happening. God is the thing to which he is praying—the goal he is trying to reach. God is also the thing inside him which is pushing him on—the motive power. God is also the road or bridge along which he is being pushed to that goal. So that the whole threefold life of the three-personal Being is actually going on in that ordinary little bed- room where an ordinary man is saying his prayers. The man is being caught up into the higher kinds of life—what I called Zoe or spiritual life: he is being pulled into God, by God, while still remaining himself.” – C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity