Volume XV, Issue VI

Agony and Ecstasy

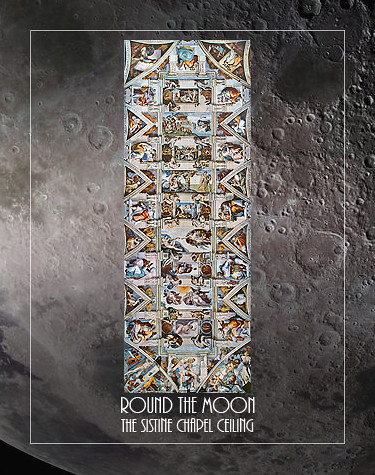

Michelangelo's Magnificent Sistine Chapel Ceiling

The Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

On November 1, 1512, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, painted by Michelangelo, was exhibited to the public for the first time. When I was a boy, my Father went to Rome as part of his work for the International Space Program. He brought me several sets of art slides of the city. My favorite was a shot of the entire ceiling that showed clearly all nine scenes from the Bible and the Twelve Apostles. It is a fascinating picture and one can explore and admire it for hours on end.

Charlton Heston played the great artist in the 1965 film The Agony and the Ecstasy. Michelangelo was a sculptor, not primarily a fresco artst, so he was reluctant to take the commission. He was already working on the Pope's own tomb. Pope Julius II, who in 1506 began the grand rebuilding of St. Peter's Cathedral as a symbol of Papal power, wanted to have the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel painted as well.

On May 10, 1508, the contract to begin the work was signed. Four years later the work was completed. Michelangelo was originally commissioned to paint figures of the Twelve Apostles, but he expanded the scope of the work to paint nine scenes from the Bible, among them the famous Creation of Adam, with the iconic figure of G-d's hand and Adam's touching.

To accomplish this great work, Michelangelo had to first construct a complex scaffolding that would allow the functions of the chapel to continue as the painting was being done. Being a sculptor, not a painter, he built wax models to simulate the play of light on his figures. He had to develop a slow drying plaster to allow him time to paint his fresco.

It is said that he painted the fresco lying on his back with paint dripping on his face. It is more likely that he built the scaffold so as to recline at an angle. Otherwise he could not have mixed paint and plaster. Nonetheless, he dealt with pressure from church officials who were anxious to see the project finished and his own need to invest the time necessary to 'serve the work.'

Thoughts on Imagination

Introducing the story of the designing of the Lunar Module by Grumman and their CEO Tom Kelly, [1.] Tom Hanks muses on imagination and invention: “Before painting the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo had to first construct a massive scaffolding to allow him access to the ceiling without interfering with the chapel’s daily use. He had to develop special wax models so he could study the lighting effects to be duplicated in the frescos and come up with a special slow drying plaster. He suffered constant deadline pressure from frustrated church officials and the Pope, who just wanted to see the ceiling finished. The work itself was uncomfortable and unending, with wet plaster dripping in the face of the man who was not after all a painter, but a sculptor. Such challenges arise in all the great works of human imagination, be they the creation of the world rendered upon the ceiling of a church or the view of our world evidenced by making the voyage from the earth to the moon.”

C. S. Lewis on Stories

Aslan. Painting by Bob Kirchman.

Some people seem to think that I began by asking myself how I could say something about Christianity to children; then fixed on the fairy tale as an instrument; then collected information about child-psychology and decided what age-group I’d write for; then drew up a list of basic Christian truths and hammered out “allegories” to embody them. This is all pure moonshine. I couldn’t write in that way at all. Everything began with images, a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion. At first there wasn’t even anything Christian about them; that element pushed itself in of its own accord. It was part of the bubbling.” – C. S. Lewis

The Failure of Imagination

In Evangelical Christianity

Clyde S. Kilby, in his essays on The Arts and the Christian Imagination, is pretty blunt in his assessment of the lack of art and imagination in the modern Christian community. Having been pursued and rescued by a richly creative and loving God, in Whom all created things have their very being, we nonetheless find ourselves in the house with new ‘houseparents’ who are more concerned that we learn the fine points of our beliefs rather than stand in wonder at their artistic expression. As a boy I spent hours in the woods and saw many a beautiful sky. The Psalms remind me that those ‘wasted’ hours taught me of the majesty of God. My Faith is much rooted in WONDER. In fact, over a year ago I created a retrospective show of my work and called it WONDER [click to view]. Because I saw God in the fattening buds of late Winter, the Springtime of Belief opened into my life.

When the opportunity to design publications for a mission organization presented itself, I jumped at the opportunity. Surely my gifts could help draw people into a great work. The director of the work was a man with a great vision for reaching the world, but he saw making beautiful literature about it as wasteful. He insisted that our publications follow the model of such publications as ‘Sword of the Lord.’ That publication was basically a reprint of sermons without pictures and very little margin space. As secular newspapers were experimenting with color photos and magazine-like features, our boss doubled down on making things blunt and basic. ‘You’re wasting the LORD’s money’ was his standard answer to any attempt to beautify our publications. It became a running joke among the more creative element in our department. It often went down as follows: New copy would be sent down and I would design a nice simple layout. The boss would take it and when he saw the ‘white space,’ he’d go to work to add copy, captions and diminish the scale of the photos – until the final piece indeed looked like a copy of ‘Sword of the Lord.’ This methodology actually added days to the design/production process. Tell me again about ‘wasting the LORD’s money.’ Kilby adds: “Our excuse for our asthetic failure is that we must be about the LORD’s business, the assumption being that the LORD’s business is never the asthetic business. Not only the faith delivered to the saints but the idiom, even the cliché in which it is expressed is the limit of some evangelicals’ conviction.”

This is really the outgrowth of a deeper lack of imagination and I do not wish to find fault with my old boss so much as to identify a problem in the Christian Imagination. When I learned that God’s Inspired Scriptures are indeed literature, that opened up a new joy and excitement about them. So many people come to the Holy Scriptures like it is a school text to be absorbed for the test. What if we see that our Creator can use literary devices to do such things as ‘describe the indescribable?’ Wouldn’t that enrich our reading of the Psalms? Instead of agonizing over the differences in the recounting of Creation in the beginning of Genesis, see the depiction of a great mystery in which a great truth is put forth – that ALL things have their beginning and being in God! Kilby describes how a young Jewish boy begins reading TORAH. A bit of honey is put on the page to let the boy know that there is also joy to be found in it. C. S. Lewis talks of the child who says on Easter morning: ‘Chocolate Eggs and Jesus Risen!’ The image of bride and bridegroom often is used to signify the expectancy of our faith! Kilby continues: “A great principle of art and esthetics is that of the necessity of renewal. The freshness of being, says Alfred North Whitehead, evaporates under mere repetition.”

I have come to love the great hymns because they create a progression of expectation. Think of the Hymn ‘How great Thou Art,’ which begins with wandering through the woods and ends with expectancy at the return of Christ. So many worship leaders are quick to eliminate the first verse when it is sung nowadays. Perhaps they justify it because it contains no theology but it is precisely the beginning of the unfolding joy of faith! It is worth noting that my former employer disliked the Hymn ‘This is My Father’s World’ because it didn’t just say that this present world is terrible, Christ will destroy it. Well, Revelation 21 and 22, Isaiah 60 and many other places in Scripture actually promise a renewed Heaven and Earth! Sadly, I have heard some preaching that basically said that this world is so terrible we should all hope in God’s destruction of it.

Citing Jesus’s answer to a problem posed by the Pharasees, I once heard a person say, almost with glee, “There is no MARRIAGE in Heaven.” Nothing could be further from the truth if Christ uses the imagery of Bride and Bridegroom so much. Whatever earthly marriage is, it is a literary device in the hands of our Master to describe something we will experience in His Kingdom! My kids once went to a vacation Bible school only to be told that “our pets won’t be with us in Heaven.” When Kristina Elaine Greer and I painted a vision of New Heaven and New Earth on the walls of a church, we began with the truth that Jesus in Revelation has a HORSE. We STUFFED the mural with representations of wonderful creatures – even a chocolate flax unicorn! WONDER, we felt, would lead young people to the deep truth of our faith.

Young people often wander away from the faith, disillusioned by our failure to show them the deeper wonders of it. They seek the richness of temporal experience because it gives them excitement. Some of them look for the experiential emotion to be found in Eastern mysticism. But I would propose to you that “Our WONDER is better than their (the world’s) WONDER,” simply because it is rooted in the Great Truth that existed before time! This is the BEAUTY we must pass on to our children!

Round the Moon

By Jules Verne

CHAPTER XIV

THE NIGHT OF THREE HUNDRED AND FIFTY-FOUR HOURS AND A HALF

At the moment when this phenomenon took place so rapidly, the projectile was skirting the moon's north pole at less than twenty-five miles distance. Some seconds had sufficed to plunge it into the absolute darkness of space. The transition was so sudden, without shade, without gradation of light, without attenuation of the luminous waves, that the orb seemed to have been extinguished by a powerful blow.

Melted, disappeared!" Michel Ardan exclaimed, aghast.

Indeed, there was neither reflection nor shadow. Nothing more was to be seen of that disc, formerly so dazzling. The darkness was complete. and rendered even more so by the rays from the stars. It was "that blackness" in which the lunar nights are insteeped, which last three hundred and fifty-four hours and a half at each point of the disc, a long night resulting from the equality of the translatory and rotary movements of the moon. The projectile, immerged in the conical shadow of the satellite, experienced the action of the solar rays no more than any of its invisible points.

In the interior, the obscurity was complete. They could not see each other. Hence the necessity of dispelling the darkness. However desirous Barbicane might be to husband the gas, the reserve of which was small, he was obliged to ask from it a fictitious light, an expensive brilliancy which the sun then refused.

Devil take the radiant orb!" exclaimed Michel Ardan, "which forces us to expend gas, instead of giving us his rays gratuitously." "Do not let us accuse the sun," said Nicholl, "it is not his fault, but that of the moon, which has come and placed herself like a screen between us and it."

It is the sun!" continued Michel.

It is the moon!" retorted Nicholl.

An idle dispute, which Barbicane put an end to by saying:

My friends, it is neither the fault of the sun nor of the moon; it is the fault of the projectile, which, instead of rigidly following its course, has awkwardly missed it.

To be more just, it is the fault of that unfortunate meteor which has so deplorably altered our first direction." "Well," replied Michel Ardan, "as the matter is settled, let us have breakfast. After a whole night of watching it is fair to build ourselves up a little."

This proposal meeting with no contradiction, Michel prepared the repast in a few minutes. But they ate for eating's sake, they drank without toasts, without hurrahs. The bold travelers being borne away into gloomy space, without their accustomed cortege of rays, felt a vague uneasiness in their hearts. The "strange" shadow so dear to Victor Hugo's pen bound them on all sides. But they talked over the interminable night of three hundred and fifty-four hours and a half, nearly fifteen days, which the law of physics has imposed on the inhabitants of the moon.

Barbicane gave his friends some explanation of the causes and the consequences of this curious phenomenon. "Curious indeed," said they; "for, if each hemisphere of the moon is deprived of solar light for fifteen days, that above which we now float does not even enjoy during its long night any view of the earth so beautifully lit up. In a word she has no moon (applying this designation to our globe) but on one side of her disc. Now if this were the case with the earth-- if, for example, Europe never saw the moon, and she was only visible at the antipodes, imagine to yourself the astonishment of a European on arriving in Australia."

They would make the voyage for nothing but to see the moon!" replied Michel.

Very well!" continued Barbicane, "that astonishment is reserved for the Selenites who inhabit the face of the moon opposite to the earth, a face which is ever invisible to our countrymen of the terrestrial globe."

And which we should have seen," added Nicholl, "if we had arrived here when the moon was new, that is to say fifteen days later."

I will add, to make amends," continued Barbicane, "that the inhabitants of the visible face are singularly favored by nature, to the detriment of their brethren on the invisible face. The latter, as you see, have dark nights of 354 hours, without one single ray to break the darkness. The other, on the contrary, when the sun which has given its light for fifteen days sinks below the horizon, see a splendid orb rise on the opposite horizon. It is the earth, which is thirteen times greater than the diminutive moon that we know-- the earth which developes itself at a diameter of two degrees, and which sheds a light thirteen times greater than that qualified by atmospheric strata-- the earth which only disappears at the moment when the sun reappears in its turn!"

Nicely worded!" said Michel, "slightly academical perhaps."

It follows, then," continued Barbicane, without knitting his brows, "that the visible face of the disc must be very agreeable to inhabit, since it always looks on either the sun when the moon is full, or on the earth when the moon is new."

But," said Nicholl, "that advantage must be well compensated by the insupportable heat which the light brings with it."

The inconvenience, in that respect, is the same for the two faces, for the earth's light is evidently deprived of heat. But the invisible face is still more searched by the heat than the visible face. I say that for you, Nicholl, because Michel will probably not understand."

Thank you," said Michel.

Indeed," continued Barbicane, "when the invisible face receives at the same time light and heat from the sun, it is because the moon is new; that is to say, she is situated between the sun and the earth. It follows, then, considering the position which she occupies in opposition when full, that she is nearer to the sun by twice her distance from the earth; and that distance may be estimated at the two-hundredth part of that which separates the sun from the earth, or in round numbers 400,000 miles. So that invisible face is so much nearer to the sun when she receives its rays."

Quite right," replied Nicholl.

On the contrary," continued Barbicane.

One moment," said Michel, interrupting his grave companion.

What do you want?"

I ask to be allowed to continue the explanation."

And why?"

To prove that I understand."

Get along with you," said Barbicane, smiling.

On the contrary," said Michel, imitating the tone and gestures of the president, "on the contrary, when the visible face of the moon is lit by the sun, it is because the moon is full, that is to say, opposite the sun with regard to the earth. The distance separating it from the radiant orb is then increased in round numbers to 400,000 miles, and the heat which she receives must be a little less." "Very well said!" exclaimed Barbicane. "Do you know, Michel, that, for an amateur, you are intelligent." "Yes," replied Michel coolly, "we are all so on the Boulevard des Italiens."

Barbicane gravely grasped the hand of his amiable companion, and continued to enumerate the advantages reserved for the inhabitants of the visible face.

Among others, he mentioned eclipses of the sun, which only take place on this side of the lunar disc; since, in order that they may take place, it is necessary for the moon to be in opposition. These eclipses, caused by the interposition of the earth between the moon and the sun, can last two hours; during which time, by reason of the rays refracted by its atmosphere, the terrestrial globe can appear as nothing but a black point upon the sun.

So," said Nicholl, "there is a hemisphere, that invisible hemisphere which is very ill supplied, very ill treated, by nature." "Never mind," replied Michel; "if we ever become Selenites, we will inhabit the visible face. I like the light." "Unless, by any chance," answered Nicholl, "the atmosphere should be condensed on the other side, as certain astronomers pretend." "That would be a consideration," said Michel.

Breakfast over, the observers returned to their post. They tried to see through the darkened scuttles by extinguishing all light in the projectile; but not a luminous spark made its way through the darkness.

One inexplicable fact preoccupied Barbicane. Why, having passed within such a short distance of the moon--about twenty-five miles only-- why the projectile had not fallen? If its speed had been enormous, he could have understood that the fall would not have taken place; but, with a relatively moderate speed, that resistance to the moon's attraction could not be explained. Was the projectile under some foreign influence? Did some kind of body retain it in the ether? It was quite evident that it could never reach any point of the moon. Whither was it going? Was it going farther from, or nearing, the disc? Was it being borne in that profound darkness through the infinity of space? How could they learn, how calculate, in the midst of this night? All these questions made Barbicane uneasy, but he could not solve them.

Certainly, the invisible orb was there, perhaps only some few miles off; but neither he nor his companions could see it. If there was any noise on its surface, they could not hear it. Air, that medium of sound, was wanting to transmit the groanings of that moon which the Arabic legends call "a man already half granite, and still breathing."

One must allow that that was enough to aggravate the most patient observers. It was just that unknown hemisphere which was stealing from their sight. That face which fifteen days sooner, or fifteen days later, had been, or would be, splendidly illuminated by the solar rays, was then being lost in utter darkness. In fifteen days where would the projectile be? Who could say? Where would the chances of conflicting attractions have drawn it to? The disappointment of the travelers in the midst of this utter darkness may be imagined. All observation of the lunar disc was impossible. The constellations alone claimed all their attention; and we must allow that the astronomers Faye, Charconac, and Secchi, never found themselves in circumstances so favorable for their observation.

Indeed, nothing could equal the splendor of this starry world, bathed in limpid ether. Its diamonds set in the heavenly vault sparkled magnificently. The eye took in the firmament from the Southern Cross to the North Star, those two constellations which in 12,000 years, by reason of the succession of equinoxes, will resign their part of the polar stars, the one to Canopus in the southern hemisphere, the other to Wega in the northern. Imagination loses itself in this sublime Infinity, amid which the projectile was gravitating, like a new star created by the hand of man. From a natural cause, these constellations shone with a soft luster; they did not twinkle, for there was no atmosphere which, by the intervention of its layers unequally dense and of different degrees of humidity, produces this scintillation. These stars were soft eyes, looking out into the dark night, amid the silence of absolute space.

Long did the travelers stand mute, watching the constellated firmament, upon which the moon, like a vast screen, made an enormous black hole. But at length a painful sensation drew them from their watchings. This was an intense cold, which soon covered the inside of the glass of the scuttles with a thick coating of ice. The sun was no longer warming the projectile with its direct rays, and thus it was losing the heat stored up in its walls by degrees. This heat was rapidly evaporating into space by radiation, and a considerably lower temperature was the result. The humidity of the interior was changed into ice upon contact with the glass, preventing all observation.

Nicholl consulted the thermometer, and saw that it had fallen to seventeen degrees (Centigrade) below zero. [3] So that, in spite of the many reasons for economizing, Barbicane, after having begged light from the gas, was also obliged to beg for heat. The projectile's low temperature was no longer endurable. Its tenants would have been frozen to death. [3] 1@ Fahrenheit.

Well!" observed Michel, "we cannot reasonably complain of the monotony of our journey! What variety we have had, at least in temperature. Now we are blinded with light and saturated with heat, like the Indians of the Pampas! now plunged into profound darkness, amid the cold, like the Esquimaux of the north pole. No, indeed! we have no right to complain; nature does wonders in our honor."

But," asked Nicholl, "what is the temperature outside?"

Exactly that of the planetary space," replied Barbicane.

Then," continued Michel Ardan, "would not this be the time to make the experiment which we dared not attempt when we were drowned in the sun's rays?"

It is now or never," replied Barbicane, "for we are in a good position to verify the temperature of space, and see if Fourier or Pouillet's calculations are exact."

In any case it is cold," said Michel. "See! the steam of the interior is condensing on the glasses of the scuttles. If the fall continues, the vapor of our breath will fall in snow around us."

Let us prepare a thermometer," said Barbicane.

We may imagine that an ordinary thermometer would afford no result under the circumstances in which this instrument was to be exposed. The mercury would have been frozen in its ball, as below 42@ Fahrenheit below zero it is no longer liquid. But Barbicane had furnished himself with a spirit thermometer on Wafferdin's system, which gives the minima of excessively low temperatures. Before beginning the experiment, this instrument was compared with an ordinary one, and then Barbicane prepared to use it. "How shall we set about it?" asked Nicholl.

Nothing is easier," replied Michel Ardan, who was never at a loss. "We open the scuttle rapidly; throw out the instrument; it follows the projectile with exemplary docility; and a quarter of an hour after, draw it in."

With the hand?" asked Barbicane.

With the hand," replied Michel.

Well, then, my friend, do not expose yourself," answered Barbicane, "for the hand that you draw in again will be nothing but a stump frozen and deformed by the frightful cold."

Really!"

You will feel as if you had had a terrible burn, like that of iron at a white heat; for whether the heat leaves our bodies briskly or enters briskly, it is exactly the same thing. Besides, I am not at all certain that the objects we have thrown out are still following us."

Why not?" asked Nicholl.

Because, if we are passing through an atmosphere of the slightest density, these objects will be retarded. Again, the darkness prevents our seeing if they still float around us. But in order not to expose ourselves to the loss of our thermometer, we will fasten it, and we can then more easily pull it back again."

Barbicane's advice was followed. Through the scuttle rapidly opened, Nicholl threw out the instrument, which was held by a short cord, so that it might be more easily drawn up. The scuttle had not been opened more than a second, but that second had sufficed to let in a most intense cold.

The devil!" exclaimed Michel Ardan, "it is cold enough to freeze a white bear."

Barbicane waited until half an hour had elapsed, which was more than time enough to allow the instrument to fall to the level of the surrounding temperature. Then it was rapidly pulled in.

Barbicane calculated the quantity of spirits of wine overflowed into the little vial soldered to the lower part of the instrument, and said:

A hundred and forty degrees Centigrade [4] below zero!"

[4] 218 degrees Fahrenheit below zero.

M. Pouillet was right and Fourier wrong. That was the undoubted temperature of the starry space. Such is, perhaps, that of the lunar continents, when the orb of night has lost by radiation all the heat which fifteen days of sun have poured into her.

CHAPTER XV, HYPERBOLA OR PARABOLA

We may, perhaps, be astonished to find Barbicane and his companions so little occupied with the future reserved for them in their metal prison which was bearing them through the infinity of space. Instead of asking where they were going, they passed their time making experiments, as if they had been quietly installed in their own study.

We might answer that men so strong-minded were above such anxieties-- that they did not trouble themselves about such trifles-- and that they had something else to do than to occupy their minds with the future.

The truth was that they were not masters of their projectile; they could neither check its course, nor alter its direction. A sailor can change the head of his ship as he pleases; an aeronaut can give a vertical motion to his balloon. They, on the contrary, had no power over their vehicle. Every maneuver was forbidden. Hence the inclination to let things alone, or as the sailors say, "let her run."

Where did they find themselves at this moment, at eight o'clock in the morning of the day called upon the earth the 6th of December? Very certainly in the neighborhood of the moon, and even near enough for her to look to them like an enormous black screen upon the firmament. As to the distance which separated them, it was impossible to estimate it. The projectile, held by some unaccountable force, had been within four miles of grazing the satellite's north pole.

But since entering the cone of shadow these last two hours, had the distance increased or diminished? Every point of mark was wanting by which to estimate both the direction and the speed of the projectile.

Perhaps it was rapidly leaving the disc, so that it would soon quit the pure shadow. Perhaps, again, on the other hand, it might be nearing it so much that in a short time it might strike some high point on the invisible hemisphere, which would doubtlessly have ended the journey much to the detriment of the travelers.

A discussion arose on this subject, and Michel Ardan, always ready with an explanation, gave it as his opinion that the projectile, held by the lunar attraction, would end by falling on the surface of the terrestrial globe like an aerolite.

First of all, my friend," answered Barbicane, "every aerolite does not fall to the earth; it is only a small proportion which do so; and if we had passed into an aerolite, it does not necessarily follow that we should ever reach the surface of the moon."

But how if we get near enough?" replied Michel.

Pure mistake," replied Barbicane. "Have you not seen shooting stars rush through the sky by thousands at certain seasons?"

Yes."

Well, these stars, or rather corpuscles, only shine when they are heated by gliding over the atmospheric layers.

Now, if they enter the atmosphere, they pass at least within forty miles of the earth, but they seldom fall upon it. The same with our projectile. It may approach very near to the moon, and not yet fall upon it."

But then," asked Michel, "I shall be curious to know how our erring vehicle will act in space?"

I see but two hypotheses," replied Barbicane, after some moments' reflection.

What are they?"

The projectile has the choice between two mathematical curves, and it will follow one or the other according to the speed with which it is animated, and which at this moment I cannot estimate."

Yes," said Nicholl, "it will follow either a parabola or a hyperbola."

Just so," replied Barbicane. "With a certain speed it will assume the parabola, and with a greater the hyperbola."

I like those grand words," exclaimed Michel Ardan; "one knows directly what they mean. And pray what is your parabola, if you please?"

My friend," answered the captain, "the parabola is a curve of the second order, the result of the section of a cone intersected by a plane parallel to one of the sides."

Ah! ah!" said Michel, in a satisfied tone.

It is very nearly," continued Nicholl, "the course described by a bomb launched from a mortar."

Perfect! And the hyperbola?"

The hyperbola, Michel, is a curve of the second order, produced by the intersection of a conic surface and a plane parallel to its axis, and constitutes two branches separated one from the other, both tending indefinitely in the two directions." "Is it possible!" exclaimed Michel Ardan in a serious tone, as if they had told him of some serious event. "What I particularly like in your definition of the hyperbola (I was going to say hyperblague) is that it is still more obscure than the word you pretend to define."

Nicholl and Barbicane cared little for Michel Ardan's fun. They were deep in a scientific discussion. What curve would the projectile follow? was their hobby. One maintained the hyperbola, the other the parabola. They gave each other reasons bristling with x. Their arguments were couched in language which made Michel jump. The discussion was hot, and neither would give up his chosen curve to his adversary.

This scientific dispute lasted so long that it made Michel very impatient.

Now, gentlemen cosines, will you cease to throw parabolas and hyperbolas at each other's heads? I want to understand the only interesting question in the whole affair. We shall follow one or the other of these curves? Good. But where will they lead us to?" "Nowhere," replied Nicholl.

How, nowhere?"

Evidently," said Barbicane, "they are open curves, which may be prolonged indefinitely."

Ah, savants!" cried Michel; "and what are either the one or the other to us from the moment we know that they equally lead us into infinite space?"

Barbicane and Nicholl could not forbear smiling. They had just been creating "art for art's sake." Never had so idle a question been raised at such an inopportune moment. The sinister truth remained that, whether hyperbolically or parabolically borne away, the projectile would never again meet either the earth or the moon.

What would become of these bold travelers in the immediate future? If they did not die of hunger, if they did not die of thirst, in some days, when the gas failed, they would die from want of air, unless the cold had killed them first. Still, important as it was to economize the gas, the excessive lowness of the surrounding temperature obliged them to consume a certain quantity. Strictly speaking, they could do without its light, but not without its heat. Fortunately the caloric generated by Reiset's and Regnaut's apparatus raised the temperature of the interior of the projectile a little, and without much expenditure they were able to keep it bearable.

But observations had now become very difficult. the dampness of the projectile was condensed on the windows and congealed immediately. This cloudiness had to be dispersed continually.

In any case they might hope to be able to discover some phenomena of the highest interest.

But up to this time the disc remained dumb and dark. It did not answer the multiplicity of questions put by these ardent minds; a matter which drew this reflection from Michel, apparently a just one:

If ever we begin this journey over again, we shall do well to choose the time when the moon is at the full."

Certainly," said Nicholl, "that circumstance will be more favorable. I allow that the moon, immersed in the sun's rays, will not be visible during the transit, but instead we should see the earth, which would be full. And what is more, if we were drawn round the moon, as at this moment, we should at least have the advantage of seeing the invisible part of her disc magnificently lit."

Well said, Nicholl," replied Michel Ardan. "What do you think, Barbicane?"

I think this," answered the grave president: "If ever we begin this journey again, we shall start at the same time and under the same conditions. Suppose we had attained our end, would it not have been better to have found continents in broad daylight than a country plunged in utter darkness? Would not our first installation have been made under better circumstances? Yes, evidently. As to the invisible side, we could have visited it in our exploring expeditions on the lunar globe. So that the time of the full moon was well chosen. But we ought to have arrived at the end; and in order to have so arrived, we ought to have suffered no deviation on the road."

I have nothing to say to that," answered Michel Ardan. "Here is, however, a good opportunity lost of observing the other side of the moon."

But the projectile was now describing in the shadow that incalculable course which no sight-mark would allow them to ascertain. Had its direction been altered, either by the influence of the lunar attraction, or by the action of some unknown star? Barbicane could not say. But a change had taken place in the relative position of the vehicle; and Barbicane verified it about four in the morning. The change consisted in this, that the base of the projectile had turned toward the moon's surface, and was so held by a perpendicular passing through its axis. The attraction, that is to say the weight, had brought about this alteration. The heaviest part of the projectile inclined toward the invisible disc as if it would fall upon it.

Was it falling? Were the travelers attaining that much desired end? No. And the observation of a sign-point, quite inexplicable in itself, showed Barbicane that his projectile was not nearing the moon, and that it had shifted by following an almost concentric curve.

This point of mark was a luminous brightness, which Nicholl sighted suddenly, on the limit of the horizon formed by the black disc. This point could not be confounded with a star. It was a reddish incandescence which increased by degrees, a decided proof that the projectile was shifting toward it and not falling normally on the surface of the moon.

A volcano! it is a volcano in action!" cried Nicholl; "a disemboweling of the interior fires of the moon! That world is not quite extinguished."

Yes, an eruption," replied Barbicane, who was carefully studying the phenomenon through his night glass. "What should it be, if not a volcano?"

But, then," said Michel Ardan, "in order to maintain that combustion, there must be air. So the atmosphere does surround that part of the moon."

Perhaps so," replied Barbicane, "but not necessarily.

The volcano, by the decomposition of certain substances, can provide its own oxygen, and thus throw flames into space. It seems to me that the deflagration, by the intense brilliancy of the substances in combustion, is produced in pure oxygen. We must not be in a hurry to proclaim the existence of a lunar atmosphere."

The fiery mountain must have been situated about the 45@ south latitude on the invisible part of the disc; but, to Barbicane's great displeasure, the curve which the projectile was describing was taking it far from the point indicated by the eruption. Thus he could not determine its nature exactly.

Half an hour after being sighted, this luminous point had disappeared behind the dark horizon; but the verification of this phenomenon was of considerable consequence in their selenographic studies. It proved that all heat had not yet disappeared from the bowels of this globe; and where heat exists, who can affirm that the vegetable kingdom, nay, even the animal kingdom itself, has not up to this time resisted all destructive influences? The existence of this volcano in eruption, unmistakably seen by these earthly savants, would doubtless give rise to many theories favorable to the grave question of the habitability of the moon.

Barbicane allowed himself to be carried away by these reflections. He forgot himself in a deep reverie in which the mysterious destiny of the lunar world was uppermost. He was seeking to combine together the facts observed up to that time, when a new incident recalled him briskly to reality. This incident was more than a cosmical phenomenon; it was a threatened danger, the consequence of which might be disastrous in the extreme.

Suddenly, in the midst of the ether, in the profound darkness, an enormous mass appeared. It was like a moon, but an incandescent moon whose brilliancy was all the more intolerable as it cut sharply on the frightful darkness of space. This mass, of a circular form, threw a light which filled the projectile. The forms of Barbicane, Nicholl, and Michel Ardan, bathed in its white sheets, assumed that livid spectral appearance which physicians produce with the fictitious light of alcohol impregnated with salt.

By Jove!" cried Michel Ardan, "we are hideous. What is that ill-conditioned moon?"

A meteor," replied Barbicane.

A meteor burning in space?"

Yes."

This shooting globe suddenly appearing in shadow at a distance of at most 200 miles, ought, according to Barbicane, to have a diameter of 2,000 yards. It advanced at a speed of about one mile and a half per second. It cut the projectile's path and must reach it in some minutes. As it approached it grew to enormous proportions.

Imagine, if possible, the situation of the travelers! It is impossible to describe it. In spite of their courage, their sang-froid, their carelessness of danger, they were mute, motionless with stiffened limbs, a prey to frightful terror. Their projectile, the course of which they could not alter, was rushing straight on this ignited mass, more intense than the open mouth of an oven. It seemed as though they were being precipitated toward an abyss of fire.

Barbicane had seized the hands of his two companions, and all three looked through their half-open eyelids upon that asteroid heated to a white heat. If thought was not destroyed within them, if their brains still worked amid all this awe, they must have given themselves up for lost.

Two minutes after the sudden appearance of the meteor (to them two centuries of anguish) the projectile seemed almost about to strike it, when the globe of fire burst like a bomb, but without making any noise in that void where sound, which is but the agitation of the layers of air, could not be generated.

Nicholl uttered a cry, and he and his companions rushed to the scuttle. What a sight! What pen can describe it? What palette is rich enough in colors to reproduce so magnificent a spectacle?

It was like the opening of a crater, like the scattering of an immense conflagration. Thousands of luminous fragments lit up and irradiated space with their fires. Every size, every color, was there intermingled. There were rays of yellow and pale yellow, red, green, gray-- a crown of fireworks of all colors. Of the enormous and much-dreaded globe there remained nothing but these fragments carried in all directions, now become asteroids in their turn, some flaming like a sword, some surrounded by a whitish cloud, and others leaving behind them trains of brilliant cosmical dust.

These incandescent blocks crossed and struck each other, scattering still smaller fragments, some of which struck the projectile. Its left scuttle was even cracked by a violent shock. It seemed to be floating amid a hail of howitzer shells, the smallest of which might destroy it instantly.

The light which saturated the ether was so wonderfully intense, that Michel, drawing Barbicane and Nicholl to his window, exclaimed, "The invisible moon, visible at last!"

And through a luminous emanation, which lasted some seconds, the whole three caught a glimpse of that mysterious disc which the eye of man now saw for the first time. What could they distinguish at a distance which they could not estimate? Some lengthened bands along the disc, real clouds formed in the midst of a very confined atmosphere, from which emerged not only all the mountains, but also projections of less importance; its circles, its yawning craters, as capriciously placed as on the visible surface. Then immense spaces, no longer arid plains, but real seas, oceans, widely distributed, reflecting on their liquid surface all the dazzling magic of the fires of space; and, lastly, on the surface of the continents, large dark masses, looking like immense forests under the rapid illumination of a brilliance.

Was it an illusion, a mistake, an optical illusion? Could they give a scientific assent to an observation so superficially obtained? Dared they pronounce upon the question of its habitability after so slight a glimpse of the invisible disc? But the lightnings in space subsided by degrees; its accidental brilliancy died away; the asteroids dispersed in different directions and were extinguished in the distance.

The ether returned to its accustomed darkness; the stars, eclipsed for a moment, again twinkled in the firmament, and the disc, so hastily discerned, was again buried in impenetrable night.

(to be continued)

The Summer of the Rain

By Bob Kirchman

Rain on Johnson Street in Staunton, Virginia. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Back when I was in high school, fifty years ago, my friends and I loved Summer. Hey, you got to run free in the woods and explore like Lewis and Clark. I hired myself out to the local farmers to paint fence and stack hay bales on the wagons. Life was hard work when they needed me followed by endless days walking in forests. But I was not totally a hermit, mind you. One event my friends and I looked forward to with great anticipation was the big Fourth of July fireworks display that was shot off from an island in the middle of a lake in Columbia.

Sure enough, the big day arrived and all of our families sat on the hill overlooking the lake for the big show. They even had sky-divers in the evening before the fireworks. This was going to be one big show! A low thunder rumbled in the distance but we ignored it. Surely tonight would be a beautiful night. A bit of wind was blowing. That was a good thing, or so we thought, as the smoke from intense fireworks had a habit of settling over the lake. That made the show a bit less brilliant at times.

Before you knew it, the skydivers dropped their flare and prepared to jump. The flare settled down in a pretty predictable fashion and the skydivers jumped. One thing you must know is that the tallest building in Howard County at the time was right beside the lake. As the two descended some erratic gusts rose up and the skydivers were headed right into the side of the building! They pulled their controlling lines enough to avoid it but had to land right in the lake!

A parachute in water is no longer your friend and fortunately the two skydivers got clear of their chutes and made it safely to shore – but it had been a harrowing moment for us all as we watched them. Now the storm loomed closer – right in the Western sky we watched carefully when baling hay. It was coming right at us. As the storm washed over the lake, fireworks were cancelled and we all scrambled for the Volkswagen Microbus.

The fireworks were later rescheduled. There were to have been three nights of fireworks but the rain cancelled every one. The rescheduled show was closer to Bastille Day than USA Independence Day, but we were excited to show up again. Wouldn’t you know it, a big storm cancelled that show as well. The show was scheduled several times that Summer, only to be washed out every time. Finally, sometime well into August, the show was able to go on.

The organizers of the event decided to shoot off all the fireworks at once. It was an amazing show. Charlie Gilbert at one point exclaimed that “it looks like the WHOLE ISLAND blew up!” It was a great end to a great Summer. We got several really good hay crops and I felt like I was rolling in money! It is amazing to think how happy I was to be making a dollar an hour – but that Summer there were a lot of hours. That was fifty years ago.

Today I am trying to schedule our students painting a mural and the rains keep coming. We’ve had to extend our schedule! But I’m smiling – remembering a Summer fifty years ago!

Painting the mural in Staunton. Photos by Bob Kirchman.

The Augusta Christian Educators (ACE) Co-Op of Augusta County, Virginia chose Madeline Maas's design for a mural to be painted in downtown Staunton. She completed it this past week with help from her fellow studio art students. Photo by Bob Kirchman

More Mural Photos [click to view]

Chesapeake and Ohio Bridge

Photo by Bob Kirchman

This arched stone bridge still carries rail traffic over Greenville Avenue. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Appalachian Trail

Photos by Bob Kirchman

Trailhead at Calvary Rocks in the mist.

Blackrock, along the trail in the Southern District of Shenandoah National Park.

Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus).

Guy Clark, The Carpenter

A Common Voice

[clck to read more]

By David Karaffa

A Common Voice is designed to be a place for a thorough discussion of issues that go beyond the agenda in today’s political discourse. We all get tired of the same topics and 30 second sound bites because nothing ever changes. Many of us go to the polls every year and pull the lever for the “R” or the “D.” Anything else we are told is a waste of our vote.

I don’t agree, we are all free-thinking people and to believe that we have to agree with one party on everything is just not true. We are capable of having a civil discussion about what we believe and forming ideas for the future. We should be sharing those thoughts and solutions on various topics that very rarely are explored below the surface.

This website does that. It is a thoughtful sharing of ideas. Many you may agree with; some you may not, and that is just fine. The point is to stimulate thought and encourage an exploration of issues beyond those 280 characters and one-phrase bumper stickers.

Welcome,

David Karaffa (read more)