Volume XV, Issue XV

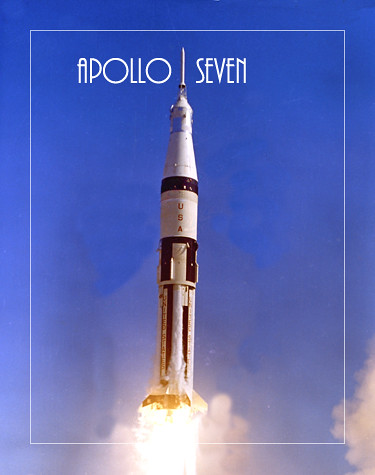

Apollo Seven

The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament sheweth his handywork.” – PSALM 19:1

Men had not flown in space since 1966. Fourteen months remained in the challenge laid down by President John F. Kennedy to put a man on the moon in this decade. The deaths of Apollo One astronauts White, Grissom and Chaffee had put a sober hold on further trips to space but on October 11, 1968, fifty years ago, Walter Schirra Jr., Commander; R. Walter Cunningham, Lunar Module Pilot and Donn F. Eisele, Command Module Pilot flew into space in the redesigned Apollo capsule aboard a Saturn 1-B Rocket. Their mission was straightforward; to prove the flight worthiness of the improved Apollo.

Oct. 11, 1968, was a hot day at Cape Kennedy, but the heat was tempered by a pleasant breeze when Apollo 7 lifted off in a two-tongued blaze of orange-colored flames. The Saturn IB, in its first trial with men aboard, provided a perfect launch, and its first stage dropped off two minutes, 25 seconds later. The S-IVB second stage took over, giving astronauts their first ride atop a load of liquid hydrogen. At five minutes, 54 seconds into the mission, Walter Schirra Jr., the commander, reported, "She is riding like a dream." About five minutes later, an elliptical orbit was achieved 140 by 183 miles above Earth.

Once Apollo 7 cleared the pad, a three-shift mission control team - led by flight directors Glynn Lunney, Eugene Kranz and Gerald D. Griffin - in Houston took over. Schirra, Donn Eisele and R. Walter Cunningham inside the command module had heard the sound of propellants rushing into the firing chambers, noticed the vehicle swaying slightly and felt the vibrations at ignition. Ten and a half minutes after launch, with little bumpiness and low g loads during acceleration, Apollo 7 reached the first stage of its journey, an orbital path 227 by 285 kilometers above Earth.

The S-IVB stayed with the CSM for about 1 1/2 orbits, then separated. Schirra fired the CSM's small rockets to pull 50 feet ahead of the S-IVB, then turned the spacecraft around to simulate docking, as would be necessary to extract an LM for a moon landing. The next day, when the CSM and the S-IVB were about 80 miles apart, Schirra and his crewmates sought out the lifeless, tumbling 59-foot craft in a rendezvous simulation and approached within 70 feet. Cunningham reported the spacecraft lunar module adapter panels had not fully deployed, which naturally reminded Thomas Stafford, the mission's capsule communicator, or capcom, of the "angry alligator" target vehicle he had encountered on his Gemini IX mission. This mishap would have been embarrassing on a mission that carried a lunar module, but the panels would be jettisoned explosively on future flights.

After this problem, service module engine performance was a joy. This was one area where the crew could not switch to a redundant or backup system. At crucial times during a lunar voyage, the engine simply had to work or they would not get back home. On Apollo 7, there were eight nearly perfect firings out of eight attempts. On the first, the crew had a real surprise. In contrast to the smooth liftoff of the Saturn, the blast from the service module engine jolted the astronauts, causing Schirra to yell "Yabadabadoo" like Fred Flintstone in the contemporary video cartoon. Later, Eisele said, "We didn't quite know what to expect, but we got more than we expected." He added more graphically it was a real boot in the rear that just plastered them into their seats. But the engine did what it was supposed to do each time it fired.

The Apollo vehicle and the CSM performed superbly. Durability was shown for 10.8 days - longer than a journey to the moon and back. With few exceptions, the other systems in the spacecraft operated as they should. Occasionally, one of the three fuel cells supplying electricity to the craft developed some unwanted high temperatures, but load-sharing hookups among the cells prevented any power shortage. The crew complained about noisy fans in the environmental circuits and turned one of them off. That did not help much, so the men switched off the other. The cabin stayed comfortable, although the coolant lines sweated and water collected in little puddles on the deck, which the crew expected after Joseph Kerwin's team test in the altitude chamber. Schirra's crew vacuumed the excess water out into space with the urine dump hose.

A momentary shudder went through the Mission Control Center in Houston when both AC buses dropped out of the spacecraft's electrical system, coincident with automatic cycles of the cryogenic oxygen tank fans and heaters. Manual resetting of the AC bus breakers restored normal service.

Three of the five spacecraft windows fogged because of improperly cured sealant compound, a condition that could not be fixed until Apollo 9. Visibility from the spacecraft windows ranged from poor to good during the mission. Shortly after the launch escape tower jettisoned, two of the windows had soot deposits and two others had water condensation. Two days later, however, Cunningham reported that most of the windows were in fairly good shape, although moisture was collecting between the inner panes of one window. On the seventh day, Schirra described essentially the same conditions.

Even with these impediments, the windows were adequate. Those used for observations during rendezvous and station-keeping with the S-IVB remained almost clear. Navigational sighting with a telescope and a sextant on any of the 37 preselected Apollo stars was difficult if done too soon after a waste-water dump. Sometimes they had to wait several minutes for the frozen particles to disperse. Eisele reported that unless he could see at least 40 or 50 stars at a time he found it hard to decide what part of the sky he was looking toward. On the whole, however, the windows were satisfactory for general and landmark observations and for out-the-window photography.

Despite minor irritations, such as smudging windows and puddling water, most components supported the operations and well-being of the spacecraft and crew as planned. For example, the waste management system for collecting solid body wastes was adequate, though annoying. The defecation bags containing a germicide to prevent bacteria and gas formation were easily sealed and stored in empty food containers in the equipment bay. But the bags certainly were not convenient and there were usually unpleasant odors. Each time they were used, it took crew members 45 to 60 minutes, causing them to wait for a time when there was no work to do and postponing it as long as possible. The crew had a total of only 12 defecations during a period of nearly 11 days. Urination was much easier, as the crew did not have to remove clothing. There was a collection service for both the pressure suits and the in-flight coveralls. Both devices could be attached to the urine dump hose and emptied into space. They had half expected the hose valve to freeze up in vacuum, but it never did.

Chargers for the batteries needed for re-entry after fuel cells departed with the service module, or SM, returned 50-75 percent less energy than expected. Most serious was the overheating of fuel cells, which might have failed when the spacecraft was too far from Earth to return on batteries, even if fully charged. But each of these anomalies was satisfactorily checked out before Apollo 8 flew.

Some of the crew's grumpiness during the mission could be attributed to physical discomfort. About 15 hours into the flight, Schirra developed a bad cold, and Cunningham and Eisele soon followed suit. A cold is uncomfortable enough on the ground, but in weightlessness it presents a different problem. Mucus accumulates, fills the nasal passages and does not drain from the head. The only relief is to blow hard, which is painful to the ear drums. So the crew of Apollo 7 whirled through space suffering from stopped-up ears and noses. They took aspirin and decongestant tablets, and discussed their symptoms with doctors.

Several days before the mission ended, they began to worry about wearing their suit helmets during re-entry, which would prevent them from blowing their noses. The buildup of pressure might burst their eardrums. Deke Slayton in mission control tried to persuade them to wear the helmets anyway, but Schirra was adamant. They each took a decongestant pill about an hour before re-entry and made it through the acceleration zone without any problems with their ears.

The CSM's service propulsion system, which had to fire the CSM into and out of the moon's orbit, worked perfectly during eight burns lasting from half a second to 67.6 seconds. Apollo's flotation bags had their first try out when the spacecraft, considered a "lousy boat," splashed down in the Atlantic southeast of Bermuda, less than 2 kilometers from the planned impact point. Landing location was 27 degrees, 32 minutes north, and 64 degrees, four minutes west. The module turned upside down, but when inflated, the brightly colored bags flipped it upright. The tired, but happy, voyagers were picked up by helicopter and deposited on the deck of the USS Essex by 8:20 a.m. EDT. Spacecraft was aboard the ship at 9:03 a.m. EDT.

Apollo 7 accomplished what it set out to do - qualifying the command and service module, and clearing the way for the proposed lunar orbit mission to follow. Its activities were of national interest. A special edition of NASA's news clipping collection called "Current News" included front page stories from 32 major newspapers scattered over the length and breadth of the nation. Although the post-mission celebrations may not have rivaled those for the first orbital flight of an American, John Glenn in 1962, enthusiasm was high and this fervor would build to even greater heights each time the lunar landing goal drew one step closer.

In retrospect it seems inconceivable, but serious debate ensued in NASA councils on whether television should be broadcast from Apollo missions, and the decision to carry the little 4 1/2-pound camera was not made until just before this October flight. Although these early pictures were crude, it was informative for the public to see astronauts floating weightlessly in their roomy spacecraft, snatching floating objects and eating the first hot food consumed in space. Like the television pictures, the food improved on later missions.

Apollo 7's achievement led to a rapid review of Apollo 8's options. The Apollo 7 astronauts went through six days of debriefing for the benefit of Apollo 8, and on Oct. 28, 1968, the Manned Space Flight Management Council chaired by George Mueller met at the Manned Spacecraft Center, investigating every phase of the forthcoming mission. The next day brought a lengthy systems review of Apollo 8's Spacecraft 103. Dr. Thomas O. Paine, NASA administrator, made the go/no-go review of lunar orbit on Nov. 11, 1968, at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. By this time, nearly all the skeptics had become converts.

The prime crew of the first manned Apollo space mission, Apollo 7 (Spacecraft 101/Saturn 205), left to right, are astronauts Donn F. Eisele, command module pilot, Walter M. Schirra Jr., commander; and Walter Cunningham, lunar module pilot.

NASA Photo.

We Have Cleared the Tower

Building the Command Module

Neil Armstrong

The First Man on the Moon

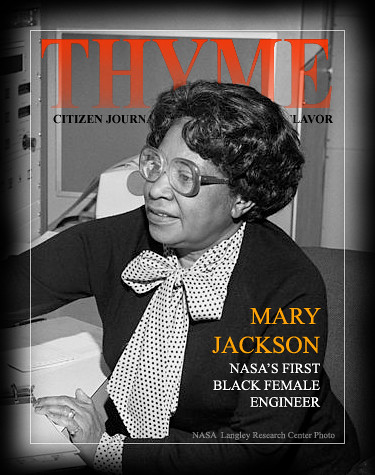

Mary Jackson.

Divine Design, Mary Jackson

How NASA Got its First Black Female Engineer

Watching the movie Hidden Figures, there was a place where I found myself clapping and crying, it is the scene where Paul, a colleague of Katherine Johnson, serves her coffee! If you have not seen the film yet, I recommend it highly. It follows the careers of three women in NASA's Langly Research Center's West Computing Division... a group of genius mathematicians who because of their skills found themselves in a highly important part of the space race with incredible responsibility.

That in itself would be a great and wonderful story but it gets even better. In the height of segregation in mid-Twentieth Century Virginia, in the 1950's, the brilliant minds of the West Computing Division were all women and they were African-American! Women were actually not strangers to engineering departments. My MOTHER had done similar work in aircraft design for the Martin Company in Baltimore. In fact, she is responsible for my FAVORITE part of the Kirchman Studio's Employee Handbook (if there is such a thing).

When Mom started at the Martin Company's Engineering Department, some old guy snarled: "Get me some coffee deary." Big mistake! Mom rose to her full almost five foot frame and snapped back: "I am here to do your calculations, and assist in design, but I will NOT fetch your coffee!" Dad, who worked in the same department, married her!

The Fay Kirchman Rule is how I honor her memory. Simply stated: "Female Colleagues are NOT required to make or fetch the coffee of their male counterparts, regardless of rank." My former assistant Kristina will attest to it. I always made the coffee and handed her a cup when she came in... and always fondly remembered Mom! The studio operated on Biblical Principle: HE-brews! So when Paul hands Katherine a cup of coffee, I remember Mom!

Mom had studied Mathematics and Physics before becoming a school teacher in Manassas, Virginia. Her career path was very similar to Mary Jackson's in that regard. Mom was doing graduate work at John's Hopkins when she was tapped to work for an engineering team at Martin. While she had to go against resistance to women in the sciences, she never had to contend with Jim Crow Laws. One of her Mentors in College was Dr. Robert Edward Loving, who taught Physics at Richmond College (before it and Westhampton were merged to become the University of Richmond). She would remember snippets of Dr. Loving's lectures in conversation with us children: "Can my little dog Garfield shake a bridge?" he would ask in a dialogue still strongly influenced by the black children who were his childhood playmates.

Mary Jackson graduated from Hampton Institute in 1942 with a dual degree in Math and Physical Sciences, and accepted a job as a math teacher at a black school in Calvert County, Maryland. Like Mom, the great war opened up the opportunity for her to go further. Langley was an important center for aeronautical research then, but it was not until 1951 that Mary joined the West Computing Division at Langley.

Margot Lee Shetterly writes: "After two years in the computing pool, Mary Jackson received an offer to work for engineer Kazimierz Czarnecki in the 4-foot by 4-foot Supersonic Pressure Tunnel, a 60,000 horsepower wind tunnel capable of blasting models with winds approaching twice the speed of sound. Czarnecki offered Mary hands-on experience conducting experiments in the facility, and eventually suggested that she enter a training program that would allow her to earn a promotion from mathematician to engineer. Trainees had to take graduate level math and physics in after-work courses managed by the University of Virginia. Because the classes were held at then-segregated Hampton High School, however, Mary needed special permission from the City of Hampton to join her white peers in the classroom. Never one to flinch in the face of a challenge, Mary completed the courses, earned the promotion, and in 1958 became NASA’s first black female engineer. That same year, she co-authored her first report, Effects of Nose Angle and Mach Number on Transition on Cones at Supersonic Speeds." [1.] Her journey to becoming an engineer is chronicled in Hidden Figures.

She worked for two decades as an engineer and authored over a dozen papers on air flow around aircraft. She became a mentor to young people, helping students build a wind tunnel at a Hampton Community Center. Thanks to the Movie Hidden Figures her story will inspire new generations of young scientists to do great things!

Mary Jackson. NASA Langley Research Center Photo.

Seeing Things in 'Living Color'

In the Vietnam era, American prisoners confined in the infamous 'Hanoi Hilton' developed some unique strategies for keeping their sanity in an environment that was designed to break them. One man, a musician, carefully drew a keyboard on a piece of scrap wood. He hid it in his cell and although it was not capable of producing sound, the man would 'sit' at it and composed pieces of music which he later was able to play. Another prisoner was a golfer. Every day he would 'play' an imaginary round in his head. Upon his release and subsequent physical rehabilitation, he went out to the golf course. His initial score was pretty low considering the years he had spent unable to play.

In the 1960's, as man raced to the moon, engineers had to develop procedures that were up to the time unheard of. My Father was an aeronautical structural engineer and in his work he tackled the problem of getting sensitive instruments and equipment into space on top of a rapidly accelerating missile. In that day the success rate for launches was pretty abysmal, something like a 50% success rate, so Dad and his team went to work imagining the forces that would assault an ascending rocket.

They developed a machine they called the Launch Phase Simulator. It was an enormous centrifuge to simulate the increased g forces of launch. A vibrator simulated the shock and vibration a spacecraft was likely to experience as it went up. The subject was mounted in a vacuum chamber and the atmospheric pressure was decreased to simulate flying into space. Finally, a system of heating and cooling apparatus simultaneously baked and cooled respective sides of the subject craft.

By imagining and simulating the possible combinations of forces assaulting an ascending spacecraft, engineers were able to make remarkable improvements in the success rate of launches.

(to be continued)

A Faerie's Ride. Illustration by Bob Kirchman

Phantasies

By George MacDonald, Chapter 2

Where is the stream?' cried he, with tears. 'Seest thou its not

in blue waves above us?' He looked up, and lo! the blue stream

was flowing gently over their heads."

~ from Novalis' Heinrich von Ofterdingen.

While these strange events were passing through my mind, I suddenly, as one awakes to the consciousness that the sea has been moaning by him for hours, or that the storm has been howling about his window all night, became aware of the sound of running water near me; and, looking out of bed, I saw that a large green marble basin, in which I was wont to wash, and which stood on a low pedestal of the same material in a corner of my room, was overflowing like a spring; and that a stream of clear water was running over the carpet, all the length of the room, finding its outlet I knew not where. And, stranger still, where this carpet, which I had myself designed to imitate a field of grass and daisies, bordered the course of the little stream, the grass- blades and daisies seemed to wave in a tiny breeze that followed the water's flow; while under the rivulet they bent and swayed with every motion of the changeful current, as if they were about to dissolve with it, and, forsaking their fixed form, become fluent as the waters.

My dressing-table was an old-fashioned piece of furniture of black oak, with drawers all down the front. These were elaborately carved in foliage, of which ivy formed the chief part. The nearer end of this table remained just as it had been, but on the further end a singular change had commenced. I happened to fix my eye on a little cluster of ivy-leaves. The first of these was evidently the work of the carver; the next looked curious; the third was unmistakable ivy; and just beyond it a tendril of clematis had twined itself about the gilt handle of one of the drawers. Hearing next a slight motion above me, I looked up, and saw that the branches and leaves designed upon the curtains of my bed were slightly in motion. Not knowing what change might follow next, I thought it high time to get up; and, springing from the bed, my bare feet alighted upon a cool green sward; and although I dressed in all haste, I found myself completing my toilet under the boughs of a great tree, whose top waved in the golden stream of the sunrise with many interchanging lights, and with shadows of leaf and branch gliding over leaf and branch, as the cool morning wind swung it to and fro, like a sinking sea-wave.

After washing as well as I could in the clear stream, I rose and looked around me. The tree under which I seemed to have lain all night was one of the advanced guard of a dense forest, towards which the rivulet ran. Faint traces of a footpath, much overgrown with grass and moss, and with here and there a pimpernel even, were discernible along the right bank. "This," thought I, "must surely be the path into Fairy Land, which the lady of last night promised I should so soon find." I crossed the rivulet, and accompanied it, keeping the footpath on its right bank, until it led me, as I expected, into the wood. Here I left it, without any good reason: and with a vague feeling that I ought to have followed its course, I took a more southerly direction.

(to be continued)

Photo by Bob Kirchman

Migrating Monarch

Photos by Bob Kirchman

Beginning the 3,000 mile migration to Winter colonies in the mountains of Central Mexico, this monarch butterfly stops briefly on a hydrangea flower.

Swoope's Sunflower Mural

A Companion to the Staunton Sunflower Mural

Here I am painting a mural in Swoope, Virginia with my “security team.” Photo by E. Argenbright.

Staunton Sunflowers

Here I am applying a clearcoat over the Staunton Sunflower Mural. Amanda Riley's vision, designed by Madeline Maas, brightens the entrance to downtown. The mural was painted by Madeline and her fellow students from Augusta Christian Educators Homeschool Coop. Ms. Maas is currently studying Nursing at Liberty University.

The Art of Community

[click to read]

These days criticism of art – whether visual, musical, or literary – is often marked by a suspicion of beauty. What happened to the belief that the creativity of the artist reflects the creativity of the Maker of heaven and earth, and that art can therefore be a channel for divine truth? Anyone who has joined with others to sing Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion or stood before a painting by Raphael or Chagall can attest to this. At such moments, art binds people together. This issue of Plough focuses on art that leads to such community: through theater, painting, music, and the objects and architecture of everyday life. And while art fosters community, building community is itself a work of creativity. (read more)

This mural, inspired by the Springhill Hollyhocks, brightens Charlottesville's Fifeville Community.

Children of the World

Mural Introduces the Beauty of IMAGO DEI

Journey to Jesus, a mural depicting the nations coming to Jesus in the New Heaven and New Earth described in Revelation 21. Mural by Kristina Elaine Greer and Bob Kirchman

Journey to Jesus [click to view larger images].

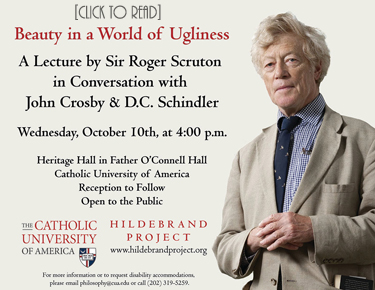

Beauty in a World of Ugliness

A Lecture by Sir Roger Scruton

Sir Roger Scruton is a profound and prolific author, having written over forty books on philosophy, religion, art, sex, and politics. Often provocative and always insightful, Sir Roger brings clarity amidst confusion to the most vital topics of our time. This event is free and open to the public, so please invite your friends, family, colleagues, and students.