Volume XVIII, Issue IV: The White City Vision

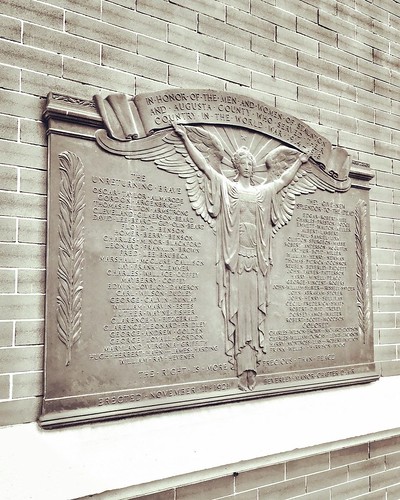

Augusta County Courthouse

An Argument for Well-Crafted Classicism

Photos by Bob Kirchman

Standing the test of time, the Augusta County Courthouse was built to this form in 1901...

The Augusta County Courthouse is a two-story, red brick, public building in Staunton, Virginia. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. It was designed by T.J. Collins, and construction ended in the Autumn of 1901. It is located in the Beverley Historic District. It is the fifth court house constructed on the site, the first having been a log building constructed in 1755. At the time the present edifice was built, the ‘City Beautiful’ Movement put forth by Daniel Burnham and other prominent architects greatly influenced civic architecture of that time. The movement, which was originally associated mainly with Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and Washington, D.C., promoted beauty not only for its own sake, but also to create moral and civic virtue among urban populations. Advocates of the philosophy believed that such beautification could promote a harmonious social order that would increase the quality of life, while critics would complain that the movement was overly concerned with aesthetics at the expense of social reform. The work of the late Roger Scruton and Leon Krier continues in that tradition.

Certainly the Classical courthouse makes a strong argument for traditional style as a civic architecture. Plans created for a relocated and much expanded Augusta County Courthouse proposed for the future added Classical elements to a decidedly modern building. The resulting design – generated by computer – perhaps illustrates the folly of legislating architectural style. Good design does indeed create spaces that lift the human experience, but such design often defies codification. Indeed, there are great Modernist buildings and poorly thought traditional ones. This is particularly true where the designer lacks a sense of appropriate proportions. It must be noted here that there is always a healthy popular support for traditional style and government should acknowledge that. Architectural review boards, as a whole however, tend to discourage healthy innovation.

...compared with the District Courts Building, built in the late Twentieth Century.

In 2016 Moseley Architects proposed a replacement courthouse to be constructed in Verona. Classical detail is added to what is essentially a modern building mass.

When the Future Came to Lake Michigan

In the Nineteenth Century, a vision for future America rose on the shore of Lake Michigan.

A Classical Foundation for America

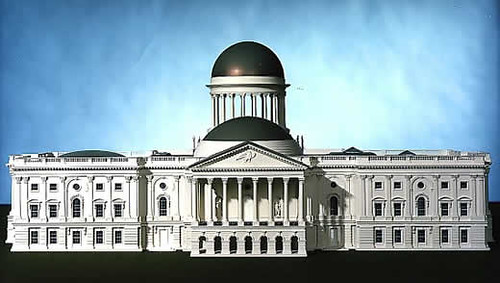

Dr. William Thornton's original design for the United States Capitol.

Classical Revivals, Past and Present

When Dr. William Thornton created the original drawings for the United States Capitol, he drew on classical forms. A new nation built her civic buildings in the style of the great ancient civilizations. White columned and stately, they rose out of the swamps of the Potomac River. Thomas Jefferson raised a replica of the Maison Carrée, a Roman temple in Nimes, France; on a hill overlooking the James River as a Capitol for the Commonwealth of Virginia. Yes, Classical Architecture indeed defined the style for America’s first civic edifices – a departure from the Georgian Style so often associated with the Colonial period.

Architects like Benjamin Henry Latrobe continued the tradition. Many fine works were built with great optimism in those early days. As our country grew Westward, a hasty hodgepodge grew up as the railroads pushed across the land. Speculators laid out sprawling Chicago in grids as far as the eye could see. It was sprawling, intimidating and unhealthy. The Nineteenth Century was a period of unparalleled growth, but there was need again for a vision to uplift that growth. In 1851 London held what is considered to be the first World’s Fair. Wonders were shown in an immense building called the Crystal Palace. Inspiration and innovation were to be found their by the many people who visited.

As the Nineteenth Century came to its end, Paris held the 1889 Exposition Universal with its grand halls and the great Eiffel Tower. Showcasing innovation and invention, the fair presented a vision for the future. The 300th anniversary of Columbus’s ‘discovery’ of the ‘New World’ presented an opportunity for America to host such a fair. Congress passed a motion for it and then the competition began for which city should play host to it. Philadelphia seemed a logical choice, but New York was the bustling port – America’s gateway to the world (as well as her largest city). Surely New York should be the site.

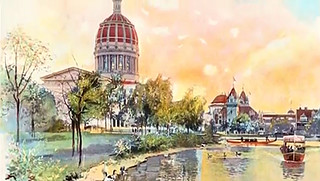

But out on the shores of Lake Michigan, stretching into the prairie, stood America’s SECOND largest city. Chicago was rapidly becoming the hub of American commerce. Chicago began in earnest to compete for the fair. Popular Mayor Carter Harrison Sr., a crafty political force, worked to bring the fair to Chicago. Honor bound to create something rivaling Paris, the city turned to Architects John Welborn Root, Daniel Burnham and Charles Atwood to design a grand vision of what an American metropolis should be. Frederick Law Olmsted, the creator of New York’s Central Park, was coerced into creating a landscaped site plan. The result was a grand campus with lakes, canals, a wooded island and surrounding those water features would stand a Classical world with colonnades and monumental fountains.

Time was not on the builders’ side, however. There was not time to build the buildings out of carved stone in the traditional manner. Instead, the builders would build steel and wooden frames covered with wood lath. Plaster would be applied to the lath (this was called ‘staff).’ This allowed the buildings to go up fast, but assured they would be temporary. Spray painting was invented to allow the ‘white’ coating that protected the plaster to go on in a timely manner. Hand painting would have been impossible in the time allotted. As it was, the fair opened for a one season run in 1893, not 1892.

Special rail lines were built to serve the fair. Visitors detraining at the lakefront would step into a surreal vision of a ‘Celestial City’ White edifices towering over reflecting pools would inspire the design of American civic architecture well into the Twentieth Century. Frank Baum saw the fair and it inspired his ‘OZ,’ also a white city, but one had to view it through green sunglasses! Walt Disney’s father worked building the fair buildings. But it was a mirage. Only one fair building was solid construction – the Palace of Fine Arts. Since it would hold treasures from around the world, the insurers demanded real masonry construction. It is the only fair building that remains today.

The Palace of Fine Arts, today the Museum of Science and Industry.

A Day at the Fair in 1893

The Palace of Fine Arts.

Aerial view of the fair showing the design of Frederick Law Olmstead for the site.

The Peristyle.

The original Ferris Wheel, sometimes also referred to as the Chicago Wheel, was designed and constructed by George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. With a height of 80.4 metres (264 ft) it was the tallest attraction at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, where it opened to the public on June 21, 1893.

Great exhibition buildings surrounding the canals...

...in a landscape created by Frederick Law Olmstead. Here is the Illinois State Pavilion.

The Liberty Bell at the World's Fair.

“Thomas Moran, a follower of the British painter J. M. W. Turner, was drawn to dramatic natural features in places such as Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon. In this view of the lagoon and central buildings constructed for the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893—an extravagant, nationalistic salute to the westward advance of “civilization”—Moran bathed the scene in the glowing colors of a vivid sunset and violet shadows that might have seemed extreme if rendered in oils.” – The Brooklyn Museum