Volume XIV, Issue XVIII

Vitus Bering's Voyages of Discovery

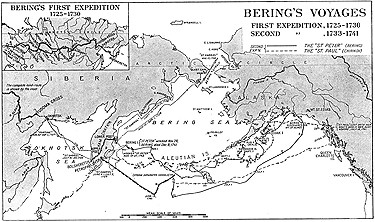

Vitus Jonassen Bering was born in Horsens, Denmark in 1681. He became a lieutenant in the Russian navy of Tsar Peter the Great in 1704. During the Great Northern War he served in both the Black and Baltic seas. In January 1725 Peter I asked Bering to lead an expedition to discover the extent of Siberia and establish a foothold in North America. He was also charged with the exploration of a possible Northeast Passage, which would allow one to sail around Siberia to China. This First Kamchatka Expedition began with a 6000 mile trek through the Siberian wilderness to Okhotsk. The party reached Okhotsk on September 30, 1726. They built the ship Gabriel there and set sail traveling Northward on July 14, 1728. He rounded the East Cape of Siberia on August 14 of that same Summer. The coast now had turned West and Bering had sighted no land beyond them to the East so he turned back at latitude 67° 18' to avoid being trapped by Winter weather. The expedition wintered at Kamchatka and Bering observed signs indication land to the East, but returned to St. Petersburg in March of 1730.

In 1733, in the wake of criticism that he had not explored Siberia beyond East Cape, Bering set out again on the Great Northern Expedition. Now charged with mapping the American Coast all the way to the first European settlement, the expedition also carried scientists and many workers who created quite a bit of discord. Arriving in Okhotsk, the party began preparations and they were ready to sail by 1740. Bering set sail for Kamchatka with two ships and wintered there. In June of 1741 he set sail again. He lost sight of the second ship, but continued North in the St. Peter, landing on present day Kayak Island. Exhausted, he turned back to Kamchatka.

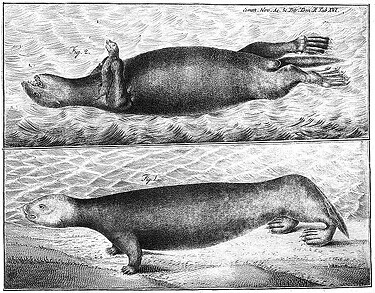

Now began a rather erratic Southwesterly voyage where Bering charted landfalls on numerous islands. In August he was too sick to leave his cabin and many of the crew began to die. Arriving in the Komandorskie Islands on November 4th, Bering Decided to winter there. His ship was severely damaged and his men were sick. Bering himself died on December 8, 1741. Out of the 77 original crew, 45 would make it to safety in 1742. Among them was Georg Wilhelm Steller, the naturalist. Driven by an “insatiable desire to visit foreign lands and to investigate their conditions and curiosities,” Steller’s journals provided valuable new information on the region. This, in addition to the mapping done by Bering, provided a valuable guide to those who followed them.

Georg Wilhelm Steller's Illustraton of a Sea Otter.

The Voyages of Vitus Bering.

The Ballad of Bering and His Friends

The Explorer of the Bering Strait

Before Captain Cook explored the Pacific, Vitus Bering made two voyages of discovery for Peter the Great. (Russian Film, No Subtitles).

Faith and Beauty III

Seeing the Divine in the Creation

Dogwood Blossom. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament sheweth his handywork.

Day unto day uttereth speech, and night unto night sheweth knowledge.

There is no speech nor language, where their voice is not heard.

Their line is gone out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world. In them hath he set a tabernacle for the sun,

Which is as a bridegroom coming out of his chamber, and rejoiceth as a strong man to run a race.

His going forth is from the end of the heaven, and his circuit unto the ends of it: and there is nothing hid from the heat thereof.

The law of the Lord is perfect, converting the soul: the testimony of the Lord is sure, making wise the simple.

The statutes of the Lord are right, rejoicing the heart: the commandment of the Lord is pure, enlightening the eyes.

The fear of the Lord is clean, enduring for ever: the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.

More to be desired are they than gold, yea, than much fine gold: sweeter also than honey and the honeycomb.

Moreover by them is thy servant warned: and in keeping of them there is great reward.

Who can understand his errors? cleanse thou me from secret faults.

Keep back thy servant also from presumptuous sins; let them not have dominion over me: then shall I be upright, and I shall be innocent from the great transgression.

Let the words of my mouth, and the meditation of my heart, be acceptable in thy sight, O Lord, my strength, and my redeemer.” – Psalm 19

Dogwood Blossom. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

The Reckless Engineer

Great Britain's Isambard Kingdom Brunel

The inspiration for my own 'Reckless Engineer' story.

Dogwood Blossoms

Photo by Bob Kirchman

From the Earth to the Moon

By Jules Verne

CHAPTER VIII: HISTORY OF THE CANNON

The resolutions passed at the last meeting produced a great effect out of doors. Timid people took fright at the idea of a shot weighing 20,000 pounds being launched into space; they asked what cannon could ever transmit a sufficient velocity to such a mighty mass. The minutes of the second meeting were destined triumphantly to answer such questions. The following evening the discussion was renewed.

My dear colleagues," said Barbicane, without further preamble, "the subject now before us is the construction of the engine, its length, its composition, and its weight. It is probable that we shall end by giving it gigantic dimensions; but however great may be the difficulties in the way, our mechanical genius will readily surmount them. Be good enough, then, to give me your attention, and do not hesitate to make objections at the close. I have no fear of them. The problem before us is how to communicate an initial force of 12,000 yards per second to a shell of 108 inches in diameter, weighing 20,000 pounds. Now when a projectile is launched into space, what happens to it? It is acted upon by three independent forces: the resistance of the air, the attraction of the earth, and the force of impulsion with which it is endowed. Let us examine these three forces.

The resistance of the air is of little importance. The atmosphere of the earth does not exceed forty miles. Now, with the given rapidity, the projectile will have traversed this in five seconds, and the period is too brief for the resistance of the medium to be regarded otherwise than as insignificant. Proceding, then, to the attraction of the earth, that is, the weight of the shell, we know that this weight will diminish in the inverse ratio of the square of the distance. When a body left to itself falls to the surface of the earth, it falls five feet in the first second; and if the same body were removed 257,542 miles further off, in other words, to the distance of the moon, its fall would be reduced to about half a line in the first second. That is almost equivalent to a state of perfect rest. Our business, then, is to overcome progressively this action of gravitation. The mode of accomplishing that is by the force of impulsion."

There's the difficulty," broke in the major.

True," replied the president; "but we will overcome that, for the force of impulsion will depend on the length of the engine and the powder employed, the latter being limited only by the resisting power of the former. Our business, then, to-day is with the dimensions of the cannon."

Now, up to the present time," said Barbicane, "our longest guns have not exceeded twenty-five feet in length. We shall therefore astonish the world by the dimensions we shall be obliged to adopt. It must evidently be, then, a gun of great range, since the length of the piece will increase the detention of the gas accumulated behind the projectile; but there is no advantage in passing certain limits."

Quite so," said the major. "What is the rule in such a case?" "Ordinarily the length of a gun is twenty to twenty-five times the diameter of the shot, and its weight two hundred and thirty-five to two hundred and forty times that of the shot."

That is not enough," cried J. T. Maston impetuously.

I agree with you, my good friend; and, in fact, following this proportion for a projectile nine feet in diameter, weighing 30,000 pounds, the gun would only have a length of two hundred and twenty- five feet, and a weight of 7,200,000 pounds." "Ridiculous!" rejoined Maston. "As well take a pistol."

I think so too," replied Barbicane; "that is why I propose to quadruple that length, and to construct a gun of nine hundred feet."

The general and the major offered some objections; nevertheless, the proposition, actively supported by the secretary, was definitely adopted.

But," said Elphinstone, "what thickness must we give it?"

A thickness of six feet," replied Barbicane.

You surely don't think of mounting a mass like that upon a carriage?" asked the major.

It would be a superb idea, though," said Maston.

But impracticable," replied Barbicane. "No, I think of sinking this engine in the earth alone, binding it with hoops of wrought iron, and finally surrounding it with a thick mass of masonry of stone and cement. The piece once cast, it must be bored with great precision, so as to preclude any possible windage. So there will be no loss whatever of gas, and all the expansive force of the powder will be employed in the propulsion."

One simple question," said Elphinstone: "is our gun to be rifled?"

No, certainly not," replied Barbicane; "we require an enormous initial velocity; and you are well aware that a shot quits a rifled gun less rapidly than it does a smooth-bore."

True," rejoined the major.

The committee here adjourned for a few minutes to tea and sandwiches.

On the discussion being renewed, "Gentlemen," said Barbicane, "we must now take into consideration the metal to be employed. Our cannon must be possessed of great tenacity, great hardness, be infusible by heat, indissoluble, and inoxidable by the corrosive action of acids."

There is no doubt about that," replied the major; "and as we shall have to employ an immense quantity of metal, we shall not be at a loss for choice."

Well, then," said Morgan, "I propose the best alloy hitherto known, which consists of one hundred parts of copper, twelve of tin, and six of brass."

I admit," replied the president, "that this composition has yielded excellent results, but in the present case it would be too expensive, and very difficult to work.

I think, then, that we ought to adopt a material excellent in its way and of low price, such as cast iron. What is your advice, major?"

I quite agree with you," replied Elphinstone.

In fact," continued Barbicane, "cast iron costs ten times less than bronze; it is easy to cast, it runs readily from the moulds of sand, it is easy of manipulation, it is at once economical of money and of time. In addition, it is excellent as a material, and I well remember that during the war, at the siege of Atlanta, some iron guns fired one thousand rounds at intervals of twenty minutes without injury."

Cast iron is very brittle, though," replied Morgan.

Yes, but it possesses great resistance. I will now ask our worthy secretary to calculate the weight of a cast-iron gun with a bore of nine feet and a thickness of six feet of metal."

In a moment," replied Maston. Then, dashing off some algebraical formulae with marvelous facility, in a minute or two he declared the following result:

The cannon will weigh 68,040 tons. And, at two cents a pound, it will cost----"

Two million five hundred and ten thousand seven hundred and one dollars."

Maston, the major, and the general regarded Barbicane with uneasy looks.

Well, gentlemen," replied the president, "I repeat what I said yesterday. Make yourselves easy; the millions will not be wanting."

With this assurance of their president the committee separated, after having fixed their third meeting for the following evening.

CHAPTER IX: THE QUESTION OF THE POWDERS

There remained for consideration merely the question of powders. The public awaited with interest its final decision. The size of the projectile, the length of the cannon being settled, what would be the quantity of powder necessary to produce impulsion?

It is generally asserted that gunpowder was invented in the fourteenth century by the monk Schwartz, who paid for his grand discovery with his life. It is, however, pretty well proved that this story ought to be ranked among the legends of the middle ages. Gunpowder was not invented by any one; it was the lineal successor of the Greek fire, which, like itself, was composed of sulfur and saltpeter. Few persons are acquainted with the mechanical power of gunpowder. Now this is precisely what is necessary to be understood in order to comprehend the importance of the question submitted to the committee.

A litre of gunpowder weighs about two pounds; during combustion it produces 400 litres of gas. This gas, on being liberated and acted upon by temperature raised to 2,400 degrees, occupies a space of 4,000 litres: consequently the volume of powder is to the volume of gas produced by its combustion as 1 to 4,000. One may judge, therefore, of the tremendous pressure on this gas when compressed within a space 4,000 times too confined. All this was, of course, well known to the members of the committee when they met on the following evening.

The first speaker on this occasion was Major Elphinstone, who had been the director of the gunpowder factories during the war.

Gentlemen," said this distinguished chemist, "I begin with some figures which will serve as the basis of our calculation. The old 24-pounder shot required for its discharge sixteen pounds of powder."

You are certain of this amount?" broke in Barbicane.

Quite certain," replied the major. "The Armstrong cannon employs only seventy-five pounds of powder for a projectile of eight hundred pounds, and the Rodman Columbiad uses only one hundred and sixty pounds of powder to send its half ton shot a distance of six miles. These facts cannot be called in question, for I myself raised the point during the depositions taken before the committee of artillery."

Quite true," said the general.

Well," replied the major, "these figures go to prove that the quantity of powder is not increased with the weight of the shot; that is to say, if a 24-pounder shot requires sixteen pounds of powder;-- in other words, if in ordinary guns we employ a quantity of powder equal to two-thirds of the weight of the projectile, this proportion is not constant.

Calculate, and you will see that in place of three hundred and thirty-three pounds of powder, the quantity is reduced to no more than one hundred and sixty pounds."

What are you aiming at?" asked the president.

If you push your theory to extremes, my dear major," said J. T. Maston, "you will get to this, that as soon as your shot becomes sufficiently heavy you will not require any powder at all."

Our friend Maston is always at his jokes, even in serious matters," cried the major; "but let him make his mind easy, I am going presently to propose gunpowder enough to satisfy his artillerist's propensities. I only keep to statistical facts when I say that, during the war, and for the very largest guns, the weight of the powder was reduced, as the result of experience, to a tenth part of the weight of the shot."

Perfectly correct," said Morgan; "but before deciding the quantity of powder necessary to give the impulse, I think it would be as well----"

We shall have to employ a large-grained powder," continued the major; "its combustion is more rapid than that of the small."

No doubt about that," replied Morgan; "but it is very destructive, and ends by enlarging the bore of the pieces."

Granted; but that which is injurious to a gun destined to perform long service is not so to our Columbiad. We shall run no danger of an explosion; and it is necessary that our powder should take fire instantaneously in order that its mechanical effect may be complete."

We must have," said Maston, "several touch-holes, so as to fire it at different points at the same time."

Certainly," replied Elphinstone; "but that will render the working of the piece more difficult. I return then to my large-grained powder, which removes those difficulties. In his Columbiad charges Rodman employed a powder as large as chestnuts, made of willow charcoal, simply dried in cast- iron pans. This powder was hard and glittering, left no trace upon the hand, contained hydrogen and oxygen in large proportion, took fire instantaneously, and, though very destructive, did not sensibly injure the mouth-piece."

Up to this point Barbicane had kept aloof from the discussion; he left the others to speak while he himself listened; he had evidently got an idea. He now simply said, "Well, my friends, what quantity of powder do you propose?"

The three members looked at one another.

Two hundred thousand pounds." at last said Morgan.

Five hundred thousand," added the major.

Eight hundred thousand," screamed Maston.

A moment of silence followed this triple proposal; it was at last broken by the president.

Gentlemen," he quietly said, "I start from this principle, that the resistance of a gun, constructed under the given conditions, is unlimited. I shall surprise our friend Maston, then, by stigmatizing his calculations as timid; and I propose to double his 800,000 pounds of powder."

Sixteen hundred thousand pounds?" shouted Maston, leaping from his seat.

Just so."

We shall have to come then to my ideal of a cannon half a mile long; for you see 1,600,000 pounds will occupy a space of about 20,000 cubic feet; and since the contents of your cannon do not exceed 54,000 cubic feet, it would be half full; and the bore will not be more than long enough for the gas to communicate to the projectile sufficient impulse."

Nevertheless," said the president, "I hold to that quantity of powder. Now, 1,600,000 pounds of powder will create 6,000,000,000 litres of gas. Six thousand millions! You quite understand?"

What is to be done then?" said the general.

The thing is very simple; we must reduce this enormous quantity of powder, while preserving to it its mechanical power."

Good; but by what means?"

I am going to tell you," replied Barbicane quietly.

Nothing is more easy than to reduce this mass to one quarter of its bulk. You know that curious cellular matter which constitutes the elementary tissues of vegetable? This substance is found quite pure in many bodies, especially in cotton, which is nothing more than the down of the seeds of the cotton plant. Now cotton, combined with cold nitric acid, become transformed into a substance eminently insoluble, combustible, and explosive. It was first discovered in 1832, by Braconnot, a French chemist, who called it xyloidine.

In 1838 another Frenchman, Pelouze, investigated its different properties, and finally, in 1846, Schonbein, professor of chemistry at Bale, proposed its employment for purposes of war. This powder, now called pyroxyle, or fulminating cotton, is prepared with great facility by simply plunging cotton for fifteen minutes in nitric acid, then washing it in water, then drying it, and it is ready for use."

Nothing could be more simple," said Morgan.

Moreover, pyroxyle is unaltered by moisture-- a valuable property to us, inasmuch as it would take several days to charge the cannon. It ignites at 170 degrees in place of 240, and its combustion is so rapid that one may set light to it on the top of the ordinary powder, without the latter having time to ignite."

Perfect!" exclaimed the major.

Only it is more expensive."

What matter?" cried J. T. Maston.

Finally, it imparts to projectiles a velocity four times superior to that of gunpowder. I will even add, that if we mix it with one-eighth of its own weight of nitrate of potassium, its expansive force is again considerably augmented."

Will that be necessary?" asked the major.

I think not," replied Barbicane. "So, then, in place of 1,600,000 pounds of powder, we shall have but 400,000 pounds of fulminating cotton; and since we can, without danger, compress 500 pounds of cotton into twenty-seven cubic feet, the whole quantity will not occupy a height of more than 180 feet within the bore of the Columbiad. In this way the shot will have more than 700 feet of bore to traverse under a force of 6,000,000,000 litres of gas before taking its flight toward the moon."

At this juncture J. T. Maston could not repress his emotion; he flung himself into the arms of his friend with the violence of a projectile, and Barbicane would have been stove in if he had not been boom-proof.

This incident terminated the third meeting of the committee.

Barbicane and his bold colleagues, to whom nothing seemed impossible, had succeeding in solving the complex problems of projectile, cannon, and powder. Their plan was drawn up, and it only remained to put it into execution.

A mere matter of detail, a bagatelle," said J. T. Maston.

(to be continued)

Skyline Drive in the Morning Mist. Photo by Bob Kirchman.