SPECIAL REPORT: Celebrating Virginia's 'Reckless Engineer'

Virginia’s ‘Reckless Engineer

He left France feeling disgraced. He had been the engineer who planned Napoleon’s strategy for the Battle of Waterloo and after that disaster he emigrated to the young Republic, the United States of America. In the mid-nineteenth century the young country was growing – flexing westward. The demand for infrastructure was strong. Claudius Crozet would find new purpose as he planned canals and railroads. His tunnels through the Blue Ridge Mountains remain an incredible accomplishment and stand as a monument to the man. This past weekend his 4237 foot long Blue Ridge Tunnel was reopened as a greenway trail. Today it is a pleasant walk but when it was completed in 1858 it was a marvel of modern engineering and it was the longest tunnel in the world.

Claudius Crozet was born on December 31, 1789 in Villefranche, France. He studied at the the École Polytechnique and became an engineer in the French Army, serving under Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1816 he resigned his commission and came to the United States. He taught at West Point and eventually came to Virginia where he became the state engineer. Here he would build the infrastructure of westward expansion. It was an era where engineers did not wear hardhats. They were more likely to sport tall top hats. Like his counterpart in England, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Crozet would stretch his calculations to design great works – and then go beyond the limits of calculation. He would create things that had not been done before.

Tunnel building in the 19th century was a dangerous business – full of unknowns – and yet men like Charles Brunel, his son Isambard and Claudius Crozet faced those unknowns. Men died in the tunnels all three men built. Cave-ins and powder accidents were an ever present danger. This was the age before Global Positioning and even the age before slide rules and yet Crozet, boring from the two sides of the mountain, brought his Blue Ridge Tunnel together within a margin of a few inches. Modern tunnel builders seldom do better.

Here follow some visits to this great work. The tunnels are still impressive today.

Claudius Crozet's Railroad Tunnels

Photos by Carrie Austin Eheart

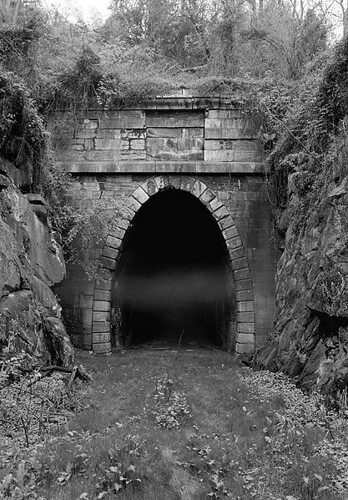

Little Rock Tunnel, at 100 feet it is the shortest in a series of tunnels through the Blue Ridge Mountains.

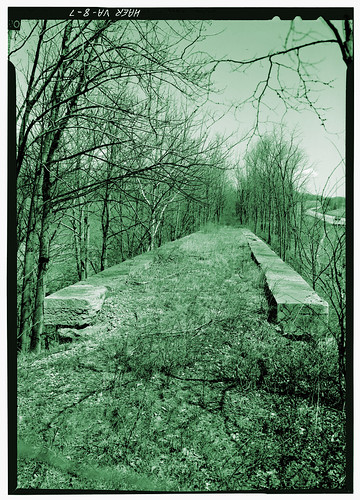

Hand excavated approaches to the Little Rock Tunnel.

Life is like a mountain railroad

With an engineer that's brave

We must make the run successful

From the cradle to the grave

Watch the curves, the fills, and tunnels

Never falter, never fail

Keep your hand upon the throttle

And your eyes upon the rail

Blessed Savior, Thou will guide us

Till we reach that blissful shore

Where the angels wait to join us

In that great forevermore

As you roll across the trestle

Spanning Jordon's swelling tide

You'll behold the Union Depot into which your train will glide

There you'll meet the superintendent

God the Father, God the Son

With a hearty joyous greetings:

“Weary Pilgrims Welcome Home”

— Life’s Railway to Heaven, In 1890, Charles Davis Tillman set to music a hymn by Baptist preacher M.E. Abbey, “Life's Railway to Heaven.” (Abbey had drawn from an earlier poem, “The Faithful Engineer,” by William Shakespeare Hays).

The Greenwood Tunnel.

Photos by Carrie Austin Eheart.

Buckingham Branch Railroad Follows Historic Path

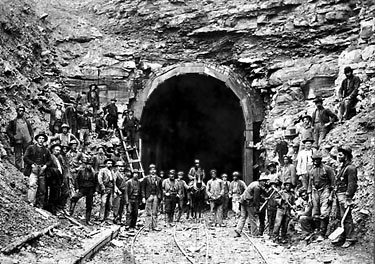

Claudius Crozet's Original Blue Ridge Tunnel. Library of Congress Image.

More than 150 years ago about 2,000 Irish immigrants changed the face of Augusta County. For eight years they joined with over 100 African-American slaves and, by hand, dug 4,262 feet through the rock of Afton Mountain to built a railroad tunnel. When they were finished in the 1850s, Richmond was connected by railroad to Staunton and Nelson County and Augusta County were connected underneath the mountain by the same rock tunnel. Some of those Irish who constructed this engineering marvel stayed in the Valley where they built a church—St. Francis Catholic Church—as well as homes, and businesses.

The story of those Irish, the African Americans, and the tunnel they built are remembered by Clann Mhór. Clann Mhór started as a research group dealing with the construction of the original Blue Ridge Railroad line that ran the 17 miles from the Mechum's River (near Ivy, Va.) up through the mountains to the South River in Waynesboro. They have evolved to include the continuation of the railroad construction further west to Staunton and Clifton Forge. Key to understanding the railroad history of the region is learning about the Irish workers hired to construct the line. Researchers with Clann Mhór, which means Great Family in Gaelic, have collected the names of over 1,900 Irish workers and their families and 100 slaves associated with the railroad. At least 941of the workers were native Irish coming mainly from the counties of Cork, Kerry, and Limerick. The men building the tunnel by hand worked six days a week, for about one dollar a day.

Using records from the C and O Historical Society, Thornrose Cemetery, and early Staunton newspapers, as well as Augusta County Courthouse records including marriages, deaths, citizenship applications, and census records, Clann Mhór has been able to document a rich picture of the lives of the railroad workers.

St. Francis Catholic Church, Staunton, Virginia. Painting by Bob Kirchman.

This 19th century photo of the tunnel and the workers was taken on the western, Augusta County, side of the tunnel. Today the original tunnel has been restored into a regional greenway open to walkers and cyclists. Trains still pass through the mountain by way of a newer tunnel constructed in 1942 [1.]

Claudius Crozet's Blue Ridge Tunnel. Photos by Bob Kirchman

Claudius Crozet surveys the opening of the Blue Ridge Tunnel in a mural by Bob Kirchman and John Pembroke, restored by Kristina Elaine Greer and Meg West in 2012.

Elliott Knob in Augusta County. The tracks heading West to Clifton Forge wind around the base of this mountain. Painting by Bob Kirchman.

Riding Through History on the Buckingham Branch

The Virginia Central Railroad was a major feat of engineering in its day as Claudius Crozet built a series of four tunnels under the Blue Ridge Mountains in 1856. Today the crews that operate the Buckingham Branch Railroad carry on the tradition.

We're riding on BB6, a GP40 diesel-electric locomotive, out of The Flats. Our crew, Don and Zane, are making the run across the mountain to Charlottesville. A number of businesses along the track depend on the railroad for bulk shipments.

We roll through Staunton and make our way to Transit Mix Concrete to deliver a car. Although much of a railroad's operation is computerized, the process of making up trains and taking them apart is still a mixture of chess game, choreography and hard work on the part of the train crew.

Switches must be unlocked and thrown, hand brakes set and unset and safety measures attended to. It looks like fun on a balmy october day as Zane moves about performing these tasks, but you have to imagine what it is like when he's doing the same job in last Winter's big snow or driving rain. A railroad man's job was tough in the Nineteenth Century and this part of it hasn't changed.

It takes a bit of leverage to throw a switch on a good day, so think of what it must be like when snow is piling up around you. We back into the first siding. It has tight curves that make for slow going. We've left most of our cars on the main line and are pushing the cement car into place. Then we need to return and couple up those we've left. We pull forward and back the entire train onto the Transit Mix siding to clear the track for a Westbound CSX train. The switch must be opened for the main line and locked before the track is considered clear.

Then you wait. Safe operation depends on constant communication and a permitting system to ensure that no Eastbound train tries to share a track with a Westbound. There are work trains to be accounted for too. A long line of empty coal cars passes. When the track is cleared we begin again. Our next stop is Augusta Coop. We will be bringing them another car from Charlottesville, so we drop one car for them on their siding. We'll put it in the fertilizer pit area later when we return.

Now we make our way out to Fishersville. We roll through Waynesboro and Basic City. We start climbing the mountain and enter the almost mile-long Blue Ridge Tunnel. This is a parallel tunnel to Crozet's original Blue Ridge Tunnel that was built in 1942 for larger wartime rail cars. We emerge at Afton and head down seven miles of descending grade that will take us to the town of Crozet.

The train moves through a series of tight curves where the track follows the original route, You can imagine what it must have been like to cut that grade through the stone by hand. We move through this section under 25 miles per hour. The Rock tunnel is next. Here is an uncased tunnel that was built by Crozet. It looks about the same as it did in the Nineteenth Century.

We pass through open cuts where the Greenwood tunnel and another tunnel have been bypassed. Then its on through Crozet. We pass the now defunct Westvaco wood lot in Ivy. "This would be a great place for a business," Don says. "Good luck on that, this is Albemarle County," I reply. When I lived in Crozet, some of my neighbors worked for Westvaco. There were the Morton's Frozen Foods plant and Acme Visible Records plant in the town itself. Both are shuttered now as well.

We enter Charlottesville where the train must crawl through town at 10 miles per hour and cannot blow her horn at grade crossings. I muse to Don about UVA students who cross streets [and railroad tracks] without looking: "What do you do about them," I ask. "You have to be ready to stop" is his answer. You are allowed to sound the horn in an emergency.

We switch cars in the Charlottesville yard by the fading evening light. There is a little preschool by the entrance to the yards and it gives me great pleasure to sit in a locomotive cab and wave to the kids. The teachers hold up some of the little guys to get a better look. I wave some more as we pass the school several times. I remember in my youth the Maryland and Pennsylvania Railroad had a track near our house. I liked to watch that train.

It is dark as we crawl back out of Charlottesville. Don spots a grey fox sitting on the track near the University of Virginia. He runs off and we spot a hole near the track. Later I spot an owl flying overhead as we run through Albemarle County. Deer are everywhere.

We return to Brand, just East of Staunton, where we shuffle around the other car we've picked up for Augusta Coop and push it into their siding. It's around 9:30pm when we return to the flats. There is paperwork to do for the crew. I pick up Don's bag of required operating manuals -- it is heavy. I'm grateful to have seen a part of the culture that built this country and to have shared it with the men who still live it.

BB6 Leaves the flats and heads through Staunton.

Don driving BB6.

Augusta Coop.

Rolling through Brand, heading East.

BB13.

In the Charlottesville Yard.

Powering up BB7 for the return trip.

Inside the Blue Ridge Tunnel.

Back at Brand.

More Photos [click to view].

Waterways Preceded Wheels

[click to read]

The oldest transportation canals in North America were constructed by Native Americans in Florida and Alabama, 1,400 years ago. In Virginia, there is no evidence of any canal prior to the arrival of European colonists. Canals were built in Virginia for two main reasons: waterpower and transportation. The smallest of the canals, designed to provide mechanical energy from falling water, were simple ditches and flumes connecting millponds/creeks to gristmills. East of Tidewater, topography-conscious colonists found places to build mills. West of Tidewater, there was enough topographic relief for falling water to power gristmills on nearly every perennial stream. Milldams in the creeks replaced the beaver dams, diverting water into millraces. Waterwheels at hundreds of grist mills were powered by a small, artificially-channeled flow of falling water that then rejoined the natural stream channel downstream of the mill. The millponds captured sediment from farm operations upstream, and blocked passage of both fish and boats, so the initial stream alterations interfered with transportation. In some cases, the canal building was for waterpower, but most of the money was focused on creating canals for transportation.

The main geographic rivalry was between advocates of improving transportation up the Potomac River through the Chesapeake and Ohio (C and O) Canal vs. supporters of improving transportation up the James River via the James River and Kanawha Canal. The goal was to steer western trade through the ports of Alexandria and Richmond. While business from Piedmont and Shenandoah farmers was desireable, the big prize was the business from the Ohio River Valley. As Americans moved west across the Allegheny Mountains, they ended up in the Mississippi River watershed. Roads were poor, and wagons pulled by horses and mules could carry only a limited amount of material, but boats could float grain, lumber, whiskey, hides, and other western products downriver to New Orleans. Eastern seaports wanted to divert that traffic across the mountains to the Atlantic Coast. The C andO Canal, as planned, would have offered a water route from Pittsburgh to Alexandria. The James River and Kanawha Canal would have intercepted the Ohio River further downstream, at Point Pleasant, and sent traffic to Richmond. Both transportation initiatives were planned initially as a series of skirting canals that would bypass the main falls/rapids (such as Great Falls) while requiring boats to rely upon water in the main river channel for most of the distance - and both grew in ambition to be totally separate channels, parallel to the rivers, with expensive locks to manage the changes in elevation. Richmond and Alexandria were not the only cities in Virginia with dreams of using canals to increase the economic "hinterland," the backcountry farming region that traded through a Chesapeake Bay port. In Fredericksburg, the Rappahannock Navigation Company tried to build a canal network 50 miles upstream of the Fall Line to the Blue Ridge, so farmers in the Rappahannock River watershed would do business with Fredericksburg merchants. Construction started in 1829, and proceded slowly. The Rappahannock Navigation Company lacked the resources to build a separate channel next to the river. Instead, it sought to build a series of locks and dams so batteaux (river boats) could float down the Rappahannock River, but bypass the shallow sections via locks adjacent to the river. After a rebuilding initiative in 1847-49, the infrastructure consisted of 80 locks (26 built of stone), 20 dams, and 15 miles of canal. As described in the nomination to the National Register of Historic Places: “A batteau lock-and-dam navigation represents a compromise, typical in the South, between an expensive continuous canal for horse-drawn canal boats, and an inexpensive but unreliable riverbed sluice navigation for batteaux. Batteau, sturdy river boats requiring shallow water, were poled and rowed so they needed no towpath, and could use small locks and narrow canals. the lock and dam system, consisting of a series of dams, each with a lock and usually a short canal, bypassed rapids and created ponds of still water. Most of the inland navigations in the South, penetrating the piedmont by way of the river valleys, were for batteaux. These systems involved various proportions of channeled riverbed (sluice navigation), land-and-dam navigation, and continuous canal.” By 1855, the Rappahannock Navigation Company was bankupt. The Fredericksburg Water Power Company converted a portion of the navigation canal into a waterpower supply for mills in the city. The power company built a wooden crib dam across the river to divert a steady supply of water to the mills, then replaced that dam in 1910 with the taller concrete Embrey Dam. The waterpower canal still transported water from the river after 1910, but now it delivered it to the Embrey Power Plant. The hydropower plant generated electricity for approximately 50 years, before being shuttered in the 1960's.In Richmond, the transportation and power canals developed as parallel projects. George Washington, a strong advocate of transportation improvements that would link the Ohio River valley with port cities on the Atlantic coast, supported the James River Company's efforts to build a transportation canal that would bypass rapids and low water spots that affected shipping down the James River. Business leaders in Richmond built a second power canal closer to the river; the Haxall Canal provided waterpower to mills rather than transportation services.

Transportation canals were "internal improvements" that spurred intense regional rivalries in Virginia. Government approval of charters for canal corporations, and investment of public funds in specific canal projects, forced governors and members of the General Assembly to find a balance between support for canals in the James River vs. Potomac River watersheds. The basic challenge was that river improvements would benefit just a narrow group of people who lived near a proposed canal project, or in the city to which the canal would steer trade. If government support for a transportation project made it easier to ship goods to Richmond, then Alexandria (and Petersburg, Fredericksburg, and Norfolk...) were jealous. Public funds spent to improve transportation in the Potomac River watershed did nothing to reduce transportation costs in the middle of the state; why should Nelson County taxpayers support a canal that would benefit farmers in Loudoun County or merchants in Alexandria? The politicians solved the problem by supporting investment in "internal improvements" across the entire state. The Dismal Swamp Canal is the oldest operating canal in the United States, with traffic starting in 1804 and continuing today as part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway. The canal benefited Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Suffolk, as well as farmers in North Carolina seeking access to the Chesapeake Bay ports. The canal crossed the watershed divide between the Elizabeth River and the Pasquotank River in North Carolina - but builders originally ignored the subtle topography. To maintain a water level high enough to float boats, locks were built near the Virginia/North Carolina line and a ditch was constructed westward to obtain water from slightly-higher Lake Drummond: Early on, the canal supporters believed that the entire region was quite flat; therefore, the canal would be nearly a river-level route, not summit level. They were wrong about this and also about the supposition that because the canal was built in a "swamp" there would be a plentiful supply of water. Droughts proved this wrong. The General Assembly, through the Board of Public Works after 1816, bought stock in various transportation projects in an early version of "public-private partnerships." The state provided up to 60% of the financing for some projects. The state was less interested in Alexandria, which had been transferred to the Federal government in 1801 for inclusion within the District of Columbia. Town merchants had to finance, without Board of Public Works assistance, the construction of the Aqueduct Bridge and extension of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal to Alexandria. The Alexandria Canal was constructed between 1841-43. Only in 1847, when Alexandria was "retroceded" back to Virginia, did the General Assembly agree to purchase Alexandria Canal bonds. The upstream residents of the James River valley, and especially the citizens of Richmond, were the primary beneficiaries of the James River and Kanawha Canal project. Residents in Culpeper, Orange, and other upstream counties - and of course Fredericksburg - planned to gain from the Rappahannock River Canal. Enhancements to the Appomattox River would benefit Petersburg and the upstream residents in that watershed. The upstream residents in the Potomac River valley, plus the residents in Alexandria, would benefit from the Potowmack Canal and its successor, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.mCanals were farm-to-market transportation systems, with the primary beneficiary being the port city at the downstream end. The most intense sectional rivalry affecting state investments in canals was between the communities in the James River watershed (with a canal terminating in Richmond) vs. those in the Potomac River watershed (with a canal terminating in Georgetown/Alexandria). Canals in both watersheds were designed to rival the Erie Canal in New York. Both were planned to connect with the Ohio River, so Midwestern farmers could do business with merchants in Virginia ports rather than with New York City. The James River Company - and the later James River and Kanawha Canal - in the James River watershed provided no economic benefits directly to Virginians living near the Potomac River or the northern Shenandoah Valley. The Potowmac Canal - and the later Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal - in the Potomac River watershed helped farmers in the lower Shenandoah Valley and the merchants of Alexandria, but took potential business away from Richmond.

George Washington was an advocate for the Potomac River connection with the Ohio River, but he too felt obliged to express support for improving the James. The elected officials in Virginia balanced the state's investments in the two canals in the Potomac River and the James River watersheds. This created a sufficient coalition in the General Assembly to overcome resistance from others regions that would gain nothing, such as Tidewater plantations that already had easy access to transatlantic shipping. George Washington in particular dreamed of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and other transportation projects uniting different sections of the new, still-fragile United States. He and his allies viewed canals as essential transportation improvements not only for reducing shipping costs for farmers east of the Alleghenies, but also for facilitating trading alliances with the new states that would be formed on the west side of the Appalachian Mountains. After fighting in the Revolutionary War to create a new nation, Washington saw his new nation begin to fall apart under the Articles of Confederation. He risked his reputation to fight politically for ratification of the Constitution in 1787-88, but knew that geography shaped destiny. He feared that settlers in the Mississippi drainage would have minimal economic ties to the East Coast. (read more)

The Port of Lexington, Virginia

Zimmerman's Lock on North River Canal

Photos by Bob Kirchman

Before the railroad, the James River Canal served as a route to Western Virginia. Our founders were building a network of canals before the steel rails came.

In the late Eighteenth Century, men like George Washington saw the need for a young nation to have infrastructure. Washington and others would oversee the building of the James River and Kanawha Canal, eventually hoping to create a water link to the Ohio River and the Mississippi. The Maury and James Rivers were already used for commerce to the coast by bateaux. These disposable boats would be built for a one way trip downstream and the trip could be described as a combination of white water canoeing in a cargo boat and drifting along long sections of flatwater. By 1860 locks on the James and the North River (now the Maury) allowed canal boats to be drawn by mules upstream to Lexington. The boats were as large as 90 feet long and some had passenger accommodations.

Canal boats in Richmond, Virginia. Drawing by J. R. Hamilton

But the era of canals would be short lived. In Ellicott City, Maryland in 1830 and Charleston, South Carolina, the first steam engines would be proved on fledgling railroads. By the middle of the Nineteenth Century, Claudius Crozet and 2000 Irish tunnel builders would establish a viable railroad through the Blue Ridge Mountains. Soon it would wind its way through the Allegany Mountains. Waterways would not connect the East to the Mississippi.

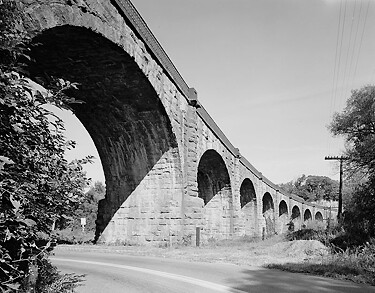

Railroads soon cut along the banks of rivers, often using the old canal towpaths, but the locks from the old canals remain in many places. The stonework is beautiful and precise. The builders obviously created a work to last for the ages. As the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad built a branch South into Lexington, the engineers of that road would build fine stone viaducts in the same tradition. Many of those remain as well including a beautiful multi-arched one just South of Staunton, Virginia which may be seen from Interstate 81.

Concrete rivers carry the commerce of our day but it is good to remember that our founders saw this commerce as essential to a nation at its beginning.

Photo of a canal boat.

Zimmerman's Lock on the Maury River. The gates opened back into these recesses in the lock walls.

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Stone Bridges Built to Endure

The Valley Railroad, a branch of the Baltimore and Ohio, once ran all the way to Lexington, Virginia crossing this fine stone bridge. Photos by Bob Kirchman.

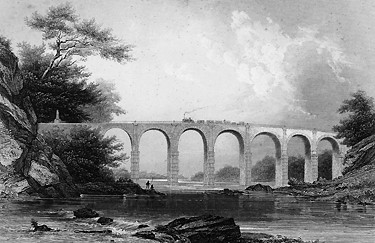

Although American railroads became known for wooden trestles and iron bridges, it is worth noting that the engineers of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad built fine stone bridges with smooth roman arches in the early days of the railroad. Two particularly fine examples are this bridge near Staunton, Virginia and the Thomas Viaduct on the road between Baltimore and Washington DC which still carries trains today.

The Thomas Viaduct spans the Patapsco River and Patapsco Valley between Relay and Elkridge, Maryland, USA. It was commissioned by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; built between July 4, 1833, and July 4, 1835; and named for Philip E. Thomas, the company's first president.

At its completion, the Thomas Viaduct was the largest bridge in the United States and the country's first multi-span masonry railroad bridge to be built on a curve. It remains the world's oldest multiple arched stone railroad bridge. In 1964, it was designated as a National Historic Landmark.

The viaduct is now owned and operated by CSX Transportation and still in use today, making it one of the oldest railroad bridges still in service.

This Roman-arch stone bridge is divided into eight spans. It was designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, II, then B and O's assistant engineer and later its chief engineer. The main design problem to overcome was that of constructing such a large bridge on a curve. The design called for several variations in span and pier widths between the opposite sides of the structure. This problem was solved by having the lateral pier faces laid out on radial lines, making the piers essentially wedge-shaped and fitted to the 4-degree curve.

The viaduct was built by John McCartney of Ohio, who received the contract after completing the Patterson Viaduct. Caspar Wever, the railroad's chief of construction, supervised the work.

The span of the viaduct is 612 feet (187 m) long; the individual arches are roughly 58 feet (18 m) in span, with a height of 59 feet (18 m) from the water level to the base of the rail. The width at the top of the spandrel wall copings is 26 feet 4 inches (8 m). The bridge is constructed using a rough-dressed Maryland granite ashlar from Patapsco River quarries, known as Woodstock granite.[6] A wooden-floored walkway built for pedestrian and railway employee use is four feet wide and supported by cast iron brackets and edged with ornamental cast iron railings. The viaduct contains 24,476 cubic yards (18,713 m3) of masonry and cost $142,236.51, an estimated $2,769,917.36 in 2007 dollars. [Wikipedia]

The Thomas Viaduct across the Patapsco River. Library of Congress Photo. [1.]

Riding Railroading's Romantic Beginnings

Wind Power on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

AEolus sails down the Baltimore and Ohio tracks. From the Collections of the B and O Railroad Museum, used with permission.

A recent CSX Transportation radio spot invites canines in cars to "ride the wind, doggies!" It is a reference to the open roads created by CSX trains taking freight off the highways and a doggie's desire to ride in a car with his head sticking out of the open window. Railroading's early days briefly offered another opportunity to "ride the wind" as a unique experiment in motive power took place on America's first operating rail line.

In the early days of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the motive power was provided by horses. The carriages were pulled along the tracks by fine animals selected for this purpose. The building that housed stables and a blacksmith shop in Ellicott's Mills still stands. But horsepower would soon become a standard instead of a literal fact. Peter Cooper's small locomotive with its upright boiler would define the future of railroading. Still, there was a brief period in railroad history where passengers could literally ride the wind.

Evan Thomas of Baltimore constructed an experimental wicker car with a sail which he named the "AEolus." When there was enough wind blowing in direction to make it functional it was operated on the tracks between Baltimore and Ellicott's Mills.

The Russian Ambassador, Baron de Krudner came to observe the operationof the experimental car and actually handled the sail on the trip. He was presented by the President of the railroad with a model of the car. This led to an exchange of American engineers who helped construct Russia's rail system.

The demonstration of Cooper's steam locomotive set the direction for railroad operation. The Fourth Annual Report of the B and O Railroad in 1830 states:

Experience with regard to the celerity of the conveyance of passengers during the preceeding four months on the first 13 miles of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, is of the most cheerful and convincing character. The practicability of maintaining a speed of 10 miles per hour with horses has been exhibited. With proper relays,this rate of traveling may be continued through any length of railway, the ascent and descents of which shall not exceed about 30 feet per mile.

Within the last few months, the improvements to locomotive steam engines have been such as to insure their general use on all railways of suitable gradation, and where fuel is cheap." [2.]

Wood and coal would fuel the first boilers. Riding the train could be a dirty experience as smoke and cinders wreaked havoc on the wardrobes of female travelers. Clean coal was used and promoted by the New York Central in this little rhyme:

Says Phoebe Snow

about to go

upon a trip to Buffalo

"My gown stays white

from morn till night

Upon the Road of Anthracite"

The modern railroad saw the use of diesel and electric power. Welded rails and modern track alignment would finally create the illusion of a smooth and effortless glide down the tracks.

21st Century railroads would like to harness the energy of wind farms to power their catenaries [the overhead wires providing power to locomotives], but even now, as during the Nineteenth Century, the winds remain as fickle as they are romantic.

2. The early motive power of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad By Joseph Snowden Bell, p. 5.

1858 Engraving of the Thomas Viaduct on the then Baltimore and Washington Railroad, a subsidiary of the Baltimore and Ohio.

Engraving from The United States Illustrated, Charles A. Dana, Editor, c. 1858. Retrieved from Historic American Engineering Record; Library of Congress [3.]

Viaduct of the Baltimore and Washington Railroad

from The United States Illustrated, Charles A. Dana, Editor, c. 1858

The traveler may well discern in the viaduct of a railroad, a monumental atonement on the part of surveyors and engineers for the injuries their labors elsewhere inflict upon the picturesque beauty of the landscape. Who has not hailed with delight, upon many a railway, the passage over some viaduct, and welcomed it amid the journey through dust and cinders, as the pilgrim over the African desert welcomes the oasis and its well of crystal water? Underneath, tons of smoothly hewn granite press deeply into the bed of the river, a whiff of whose cooling vapor, at least, comes into the passenger’s nostrils, as he dashes over a superstructure, the length of which would have been the admiration of the Romans, whose creek like Tiber might have provoked the sneer of a “go ahead” engineer.

The “Pons Narniensis,” whose framer was the imperial Augustus; the arches of Trajan over the Danube, and the bridge of Alcántara across the Spanish Tagus, have long been famous in ancient history, whilst America, for the accommodation of no imperial cortege, but of the masses of the people, has rivalled them all in her numerous railroad viaducts, and especially in the Starrucca Viaduct upon the Erie Railroad.

The one given in the engraving was of the first built in the country, although exceeded by the one above named in length, breadth, height, and the span of the arches, it is not surpassed for beauty of location and compactness of execution. But alas, by only one or two of the thousand passengers who rush along its surface, is this beauty and compactness noticed. Now and then a passenger drops off at the neighboring station, intent upon converting his walking staff into a fishing rod, beside the shadow of its arches, or about once in a twelvemonth a detention upon the neighboring “switch” allows the traveller a saunter by its railing, or a hurried clamber down the rocky ledge which confines the waters of the Patuxent (actually the Patapsco) River and in great part forms its bed.” [4.]

This station at Fort Defiance, Virginia once served the Baltimore and Ohio's Valley Railroad.

Bracket detail of Lexington, Virginia's Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station, Built in 1883. Photo by Bob Kirchman.

Valley Railroad Bridge

Library of Congress Photos

The Valley Railroad Stone Bridge, built in 1874, crosses Folly Mills Creek just west of Interstate Highway 81 approximately five miles south of Staunton. The bridge is a four-span structure with an over-all length of 130 feet and a width of 15 feet, It utilizes semi-circular arches set on gently splayed piers. Slightly projecting imposts are located between the tops of the piers and the spring of the arches. Granite is used throughout as the construction material, and the facing is a rough-surface ashlar. The only change to have occurred to the bridge is the removal of the railroad ties and rails. Because of the close proximity to Interstate 81, the bridge has become a familiar landmark to travelers throughout the Valley of Virginia. The Department of Highways maintains it as part of the highway's landscaping. National Register of Historic Places.